Patents and Technology

Patents can be controversial, and some companies certainly abuse them. That said, they can also be essential to protect the value of a startup’s innovative new products.

Contents:

Patent Strategy for Startups

Terminology. Patents come in 3 major flavors: utility, design, and provisional. If we just say “patent”, we’re probably talking about a utility patent - a patent on a new and useful technology. A design patent protects the “ornamental appearance” of a new design. Finally, a “provisional” is shorthand for a “provisional patent application.” Its not a patent at all, its just a type of temporary patent application that nails down a filing date at the Patent Office.

Provisional Patent Applications A provisional can be a useful first step for early-stage technology startups. It’s essentially a temporary patent application that nails down a filing date at the Patent Office. Once the filing date is secure, the company can then delay the expense of filing the full ‘utility patent application’ for a full year.

Patents are slow and expensive. The cost varies with the complexity of the technology, but here are some ballpark figures:

- Cost of a provisional patent application: $1,000 - $3,000

- Cost of a full utility patent application: $7,000 - $15,000

Once the provisional patent application is on file, the startup has a full year to test the market for their technology. If they hit on product-market fit, they can press forward with the utility patent application. If not, they can abandon the provisional patent application, and avoid the full expense of the utility patent application.

Patent Filing Deadlines

Patents should generally be filed before you launch your product. If your product is already launched, then get any patent applications on file within 1 year of the launch date. The sooner the better. Once your product has been on the market for over a year, then any inventions it contains become part of the public domain. No patent applications will be allowed.

Patent Law

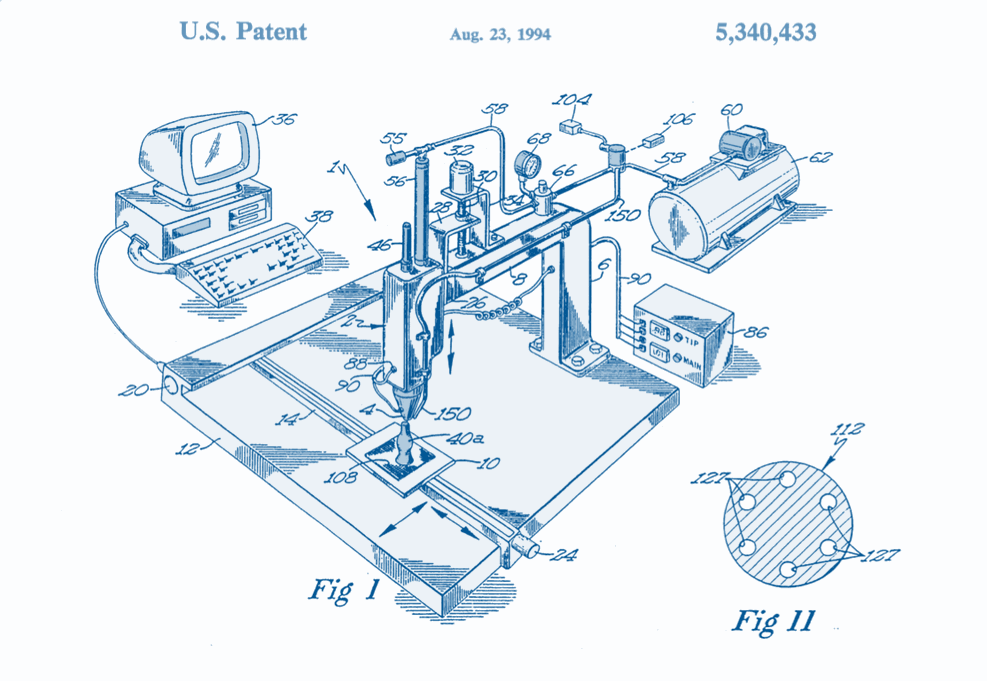

Utility Patent

A US utility patent grants the right to prevent other people from making, selling or importing a new and useful technology in the United States for a period of 20 years after the application date. It is the right to exclude only. That is, it grants the right to prevent others from selling the technology, but it does not guarantee that the patent holder herself has the rights to sell the technology.

Patents are national rights. A US patent does not automatically grant rights in any other countries.

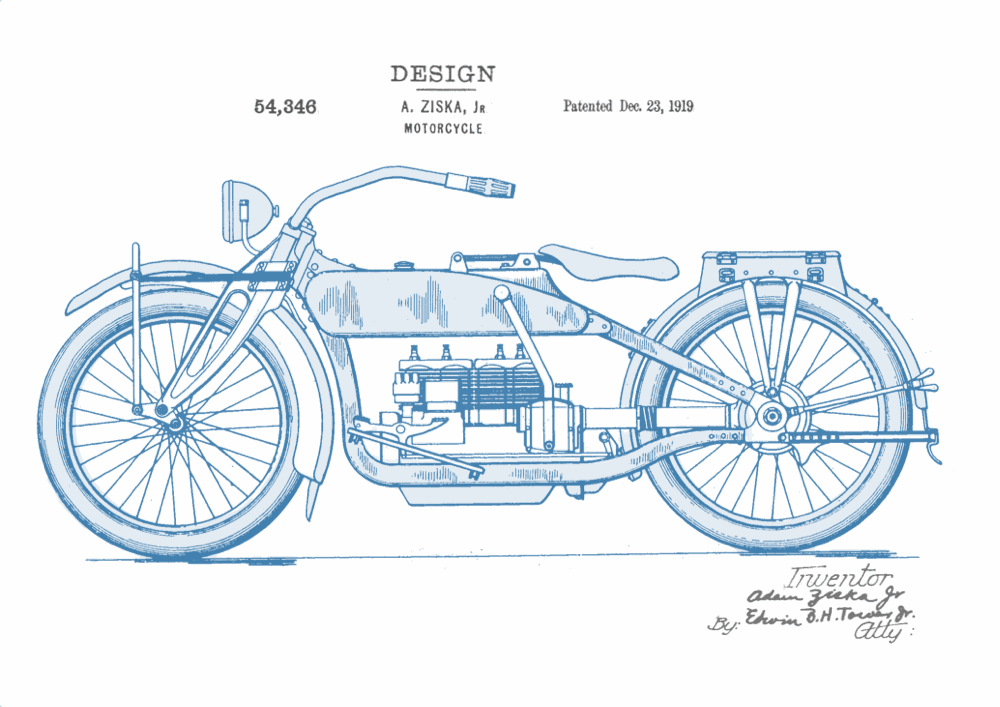

Design Patents

Design patents protect the “ornamental appearance” of a product. They can protect industrial design and physical products, as well as software user interface designs and fonts.

Patent Application Process

-

Invention Disclosure. The inventor fills out a detailed “invention disclosure form” describing the new technology. It’s often helpful to describe the invention invention in terms of problem-and-solution. Describe the problem the invention solves, and then carefully describe the details of how the invention solves this problem.

-

Novelty Search. The patent attorney may or may not conduct a “novelty search.” A novelty search is a search of the USPTO patent database (and potentially other databases) for prior art.

-

Filing. The patent attorney will draft and file your patent application. Once filed, you can label your technology as “patent pending.”

-

Publication. The patent application will be “published” 18 months after it’s filed. If a provisional application was filed, the publication takes place 18 months after the provisional. Published patent application are available to the public on the USPTO’s database. Publication can be delayed by filing a “non-publication request”, but only if the inventor is sure that she does not want to seek patent protection in foreign countries.

-

Office Actions. About 2 years after the application is filed, the a USPTO Patent Examiner will review the application. The Patent Examiner will generally issue an “Office Action” rejecting the application based on prior art. If the Patent Examiner finds a prior art document that describes the exact invention, she will reject the application under § 102 as “anticipated” by the prior art. (MPEP 2131). If the Patent Examiner can’t find prior art describing the exact invention, but can find a handful of related prior art patents that, in combination, describe the invention, then she will reject the application as “obvious” under § 103. (MPEP 2141).

-

Patent Prosecution. The patent attorney can reply to the Office Action by pointing out errors in the Patent Examiner’s reasoning or by amending the patent application to claim parts of the invention not described by the prior art. In general, no new material can be added to a patent application after it’s filed. If new material is necessary, the Patent Attorney must file a “continuation in part” application. This resets the clock on prior art, expanding the prior art pool to include more recent documents.

-

Allowance and Issue. If the Patent Examiner cannot find any prior art, she will allow the claims. The inventor pays an “issue fee” and the patent application is on its way to becoming a full patent.

Patent Lifespan

Utility Patent Lifespan A US utility patent lasts for 20 years from the date of the earliest non-provisional patent application.

Patent Term Adjustment. The 20 year patent lifespan starts from the application date. This means the longer the application is pending at the Patent Office, the shorter the actual patent lifespan. If the patent application process is delayed, applicants can ask the the Patent Office to extend the life of the issued patent. (MPEP 2700).

Maintenance Fees. The US Patent Office requires three maintenance fees to be paid: at 3.5 years, 7.5 years, and 11.5 years after the patent’s issue date. Failure to pay will result in early expiration. (MPEP 2500).

Design Patent Lifespan. A US design patent lasts for 15 years from the issue date. There are no maintenance fees to pay.

Patent Ownership

In general, a patent is initially owned by its “inventor” or “joint inventors.” Companies funding research should be careful to have their employees and contracts sign “invention assignment agreements” to transfer the patent rights over to the company. This assignments should be recorded at the USPTO within 3 months of any patent application filing (MPEP 302).

The default ownership rules for “joint inventors” can be messy. Fortunately, co-inventors can sidestep the messy default rules by assigning their ownership interests to a company (perhaps a company where they own an equal share of stock).

Who are the “Inventors”?

If a team of scientists and engineers work on a project, are they all inventors? Since the inventors are the initial owners of a patent, understanding the definition of an “inventor” is critical. “The threshold question in determining inventorship is who conceived the invention. Unless a person contributes to the conception of the invention, he is not an inventor.” (MPEP 2137.01(II)).

An inventor can consider ideas and materials from many sources, such as a suggestion from colleagues or consultants, “so long as he maintains intellectual domination of the work of making the invention down to the successful testing, selecting or rejecting as he goes, even if such suggestion or material proves to be the key that unlocks his problem.” (MPEP 2137.01(III)).

Members of a team who merely follow directions from an inventor are not themselves inventors. They may only become inventors if they contribute to the conception of the invention, such as the physical structure or operative steps. Likewise, the inventor does not need to get her hands dirty in the lab to maintain her “inventor” status. She can merely conceive an idea, and then direct underlings to conduct experiments or build prototypes. In re DeBaun, 687 F.2d 459, 463 (CCPA 1982)(“there is no requirement that the inventor be the one to reduce the invention to practice so long as the reduction to practice was done on his behalf”). (MPEP 2137.01(IV)).

Patentable Subject Matter

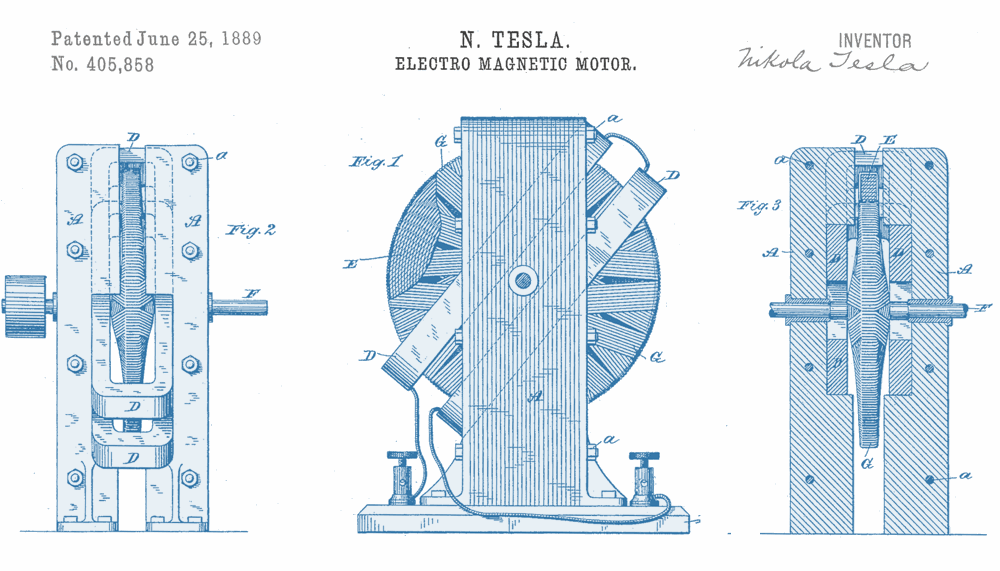

Patents are only issued to people who invent a “new and useful process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter, or any new and useful improvement thereof…” 35 USC 101. (MPEP 2104).

Prior Art

Prior art generally refers to a “printed publication” describing the technology that became public before the date of the patent application. Any public use or sale of the technology before the date of the patent application can also be prior art. (35 USC 102, MPEP 706.02).

Novelty and Anticipation

Patents must be novel. That is, the technology must not have been precisely described in any prior art. (MPEP 2141). Stated differently, a patent claim is anticipated if a single piece of prior art describes “every element” of the claim.

This is usually an easy question to answer. However, novelty alone is not enough for a patent. The technology must also be “non-obviousness.”

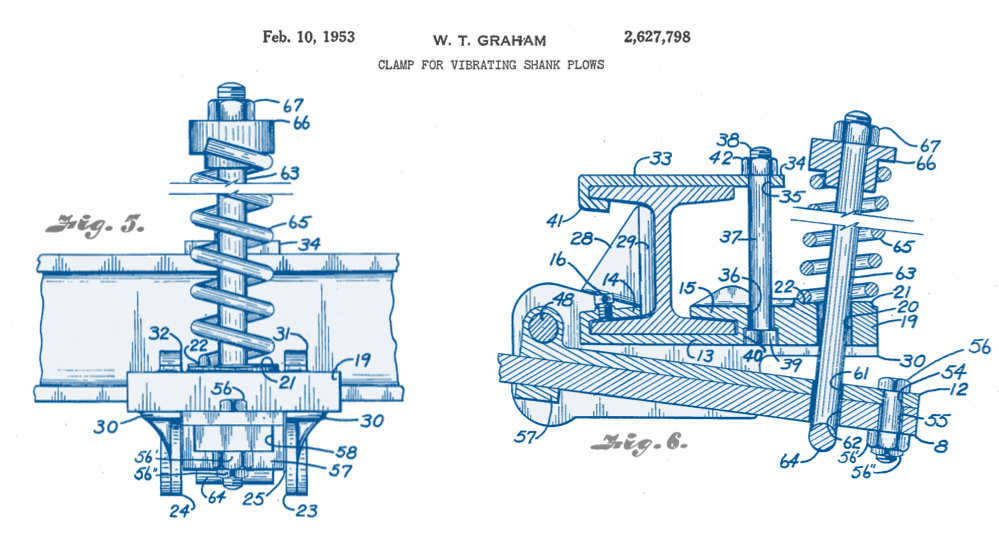

Obviousness

To qualify for a patent, a technology must be “non-obvious.” Ask yourself, on the date the application was filed, would the technology have been obvious to an ordinary engineer or scientist in the field? If so, it’s obvious and cannot be patented. (MPEP 2141). This is obviously a subjective question, and reasonable people can reach different conclusions. However, courts have issued guidelines to help us evaluate the question more methodically.

(Graham Patent from Graham v. John Deere, 383 US 1 (1966).)

New Use for an Existing Product

In general, a new use for an existing product is not patentable. In limited circumstances, a new use for an existing structure based on newly discovered properties of the structure might be patentable as a process of use. (MPEP 2112).

New Use for an Existing Process

A new use for an existing process can be patented, but the prosecution may be difficult, and the resulting patent likely to provide only narrow protections. (MPEP 2112.02).

Using a Conventional Process to Make a Non-Obvious Product

There is no per se rule here. Sometimes a conventional process can be patented if it is limited to making or using a nonobvious product. The test for obviousness under 35 U.S.C. 103 requires a highly fact-dependent analysis involving taking the claimed subject matter as a whole and comparing it to the prior art. “A process yielding a novel and nonobvious product may nonetheless be obvious; conversely, a process yielding a well-known product may yet be nonobvious.” (MPEP 2116) (citing, TorPharm, Inc. v. Ranbaxy Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 336 F.3d 1322, 1327 (Fed. Cir. 2003).

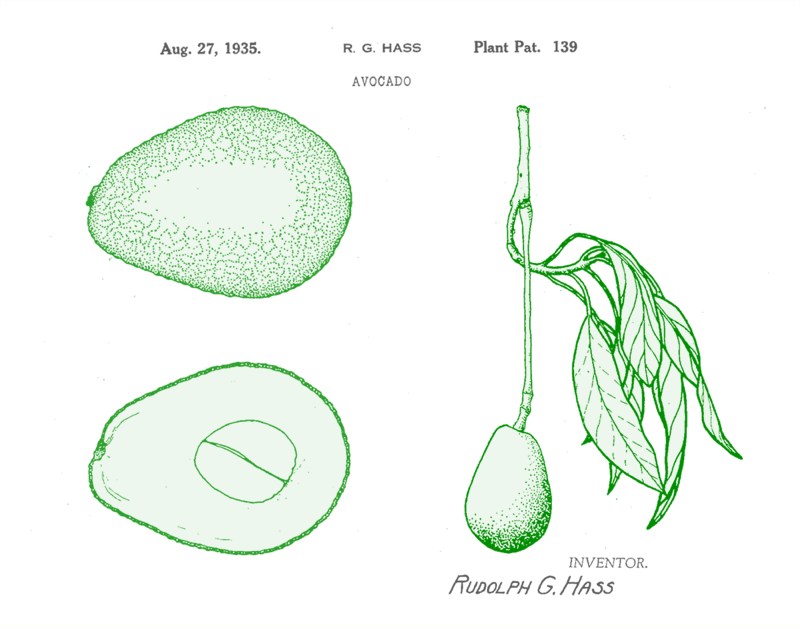

Fun fact: plants can be patented. Plant patents protect newly discovered varieties of asexually reproducing plants. Plants found in nature (uncultivated) cannot be patented.