The USPTO recently issued new patent examination guidelines for determining whether a patent application claims “patent-eligible subject matter” or unpatentable “laws of nature.” The memo addresses 2 recent Supreme Court cases, Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, and Mayo v. Prometheus Labs, and instructs patent examiners on applying these cases. The most useful portion is the list of 6 factors that weigh in favor of patentability (labelled a-f) and the 6 factors weighing against it (g-l).

Be careful not to confuse the “laws of nature” analysis with “abstract ideas” analysis. Both abstract ideas and laws of nature are ineligible for patents. But the test for whether something is an abstract idea comes from Bilski v. Kappos and has its own separate USPTO memo.

The USPTO’s March 4, 2014 memo on unpatentable laws of nature is copied below (lightly edited for length):

To: Patent Examining Corps

From: Andrew H. Hirshfeld, Deputy Commissioner for Patent Examination Policy

SUBJECT: 2014 Procedure For Subject Matter Eligibility Analysis of Claims Reciting or Involving Laws of Nature, Natural Phenomena, and/or Natural Products

The attached guidance memorandum implements a new procedure to address changes in the law relating to subject matter eligibility under 35 U.S.C. § 101 in view of recent court decisions including Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. _, 133 S. Ct. 2107, 2116, 106 USPQ2d 1972 (2013), and Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. _, 132 S. Ct. 1289, 101 USPQ2d 1961 (2012).

All claims (i.e., machine, composition, manufacture and process claims) reciting or involving laws of nature/natural principles, natural phenomena, and/or natural products should be examined using the Guidance. The new procedure set forth in the Guidance will assist examiners in determining whether a claim reflects a significant difference from what exists in nature and thus is eligible, or whether a claim is effectively drawn to something that is naturally occurring, like the claims found ineligible by the Supreme Court in Myriad.

Examiners are reminded that § 101 is not the sole tool for determining patentability; where a claim encompasses a judicial exception such as a natural product, sections 102, 103, and 112 will provide additional tools for ensuring that the claim meets the conditions for patentability. Under principles of compact prosecution, Office personnel should state all non-cumulative reasons and bases for rejecting claims in the first Office action.

The Office is issuing the following guidance for use in subject matter eligibility determinations of all claims (i.e., machine, composition, manufacture and process claims) reciting or involving laws of nature/natural principles, natural phenomena, and/or natural products. This guidance supersedes the June 13, 2013 memorandum to the corps titled “Supreme Court Decision in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc.”

There is no change to examination of claims reciting an abstract idea, which should continue to be analyzed for subject matter eligibility using the existing guidance in MPEP § 2106(II).

This guidance addresses the impact of Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 569 U.S. __, 133 S. Ct. 2107, 2116, 106 USPQ2d 1972 (2013) (Myriad) on the Supreme Court’s long-standing “rule against patents on naturally occurring things”, as expressed in its earlier precedent including Diamond v. Chakrabarty, 447 U.S. 303 (1980) (Chakrabarty), and Mayo Collaborative Services v. Prometheus Laboratories, Inc., 566 U.S. __, 132 S. Ct. 1289, 101 USPQ2d 1961 (2012) (Mayo). See Myriad, 133 S. Ct. at 2116. Myriad relied on Chakrabarty as “central” to the eligibility inquiry, and re-affirmed the Office’s reliance on Chakrabarty’s criterion for eligibility of natural products (i.e., whether the claimed product is a non-naturally occurring product of human ingenuity that is markedly different from naturally occurring products). Id. at 2116-17. Myriad also clarified that not every change to a product will result in a marked difference, and that the mere recitation of particular words (e.g., “isolated”) in the claims does not automatically confer eligibility. Id. at 2119. See also Mayo, 132 S. Ct. at 1294 (eligibility does not “depend simply on the draftsman’s art”). Thus, while the holding in Myriad was limited to nucleic acids, Myriad is a reminder that claims reciting or involving natural products should be examined for a marked difference under Chakrabarty.

This guidance includes four sections:

- Part I – discussing the overall process for analyzing subject matter eligibility;

- Part II – explaining how to determine whether the claim as a whole recites eligible subject matter (something significantly different than a judicial exception);

- Part III – providing multiple examples; and

- Part IV – providing a new form paragraph to be used when rejecting claims in accordance with this guidance.

I. Overall Process for Subject Matter Eligibility Under 35 U.S.C. 101

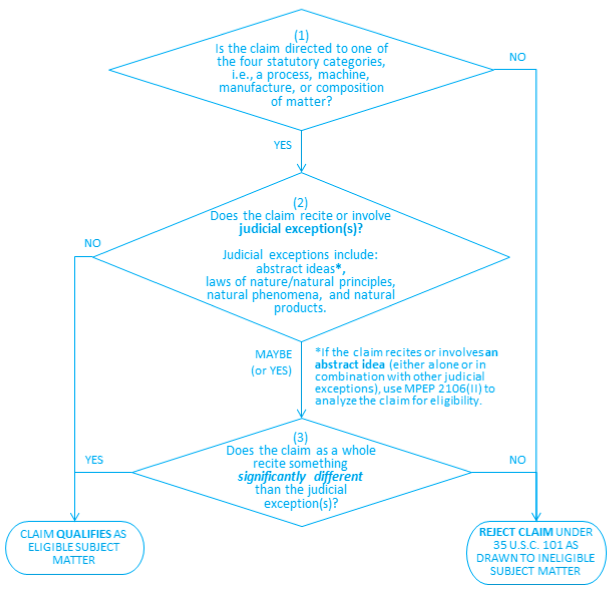

After determining what applicant invented and establishing the broadest reasonable interpretation of the claim in accordance with MPEP § 2103, walk through the three questions in the flowchart below to determine whether the claim is drawn to patent-eligible subject matter. If not, then the claim is prima facie ineligible, and the claim should be rejected using revised form paragraph 7.05.13 (shown in Part IV).

1. Question 1: Is the claimed invention directed to one of the four statutory patent-eligible subject matter categories: process, machine, manufacture, or composition of matter? 1

[footnote 1. A summary of the four statutory subject matter categories, as they have been interpreted by the courts, is provided in MPEP § 2106(I). As a reminder, claims to humans per se are not directed to a statutory subject matter category, pursuant to Section 33(a) of the America Invents Act.]

If no, the claim is not eligible for patent protection and should be rejected under 35 U.S.C. 101, for at least this reason. See MPEP § 706.03 for a description of the appropriate form paragraphs to use in rejecting the claim.

If yes, proceed to Question 2.

2. Question 2: Does the claim recite or involve one or more judicial exceptions?

If no, the claim is patent-eligible, and the analysis is complete.

If yes, or if it is unclear whether the claim recites or involves a judicial exception, proceed to Question 3.

Judicial exceptions include abstract ideas, laws of nature/natural principles, natural phenomena, and natural products.2

[footnote 2. As described in MPEP § 2106, in addition to the terms laws of nature, physical phenomena, and abstract ideas, judicial exceptions have been described using various other terms, including natural phenomena, products of nature, natural products, naturally occurring things, scientific principles, systems that depend on human intelligence alone, disembodied concepts, mental processes and disembodied mathematical algorithms and formulas, for example. The exceptions reflect the judicial view that these fundamental tools of scientific and technological work are not patentable.]

In particular, claimed subject matter that must be analyzed under Question 3 to determine whether it is a natural product includes, but is not limited to: chemicals derived from natural sources (e.g., antibiotics, fats, oils, petroleum derivatives, resins, toxins, etc.); foods (e.g., fruits, grains, meats and vegetables); metals and metallic compounds that exist in nature; minerals; natural materials (e.g., rocks, sands, soils); nucleic acids; organisms (e.g., bacteria, plants and multicellular animals); proteins and peptides; and other substances found in or derived from nature.

If there is any doubt as to whether the claim recites a judicial exception (e.g., the claim recites something similar to a natural product), the claim requires further analysis under Question 3. For example, if the claimed product is a protein or a mineral, then the analysis must proceed to Question 3, in order to determine whether the protein or mineral is claimed in a manner that is significantly different than naturally occurring proteins or minerals. This is the case regardless of whether particular words (e.g., “isolated”, “recombinant”, or “synthetic”) are recited in the claim.

Question 3: Does the claim as a whole recite something significantly different than the judicial exception(s)?

If the claim recites an abstract idea (whether alone or in combination with other judicial exceptions), it should be analyzed for subject matter eligibility using only the existing guidance in MPEP § 2106(II).

Otherwise, answer this Question using the factor-based analysis of “significantly different” that is discussed below in Part II.

If the answer is no (i.e., the factor-based analysis indicates that the claim as a whole is not significantly different than the judicial exception(s)), the claim is not patent-eligible and should be rejected under 35 U.S.C. 101. See revised form paragraph 7.05.13 (reproduced below in Part IV), which should be used in rejecting the claim.

If the answer is yes (i.e., the factor-based analysis indicates that the claim as a whole is significantly different than the judicial exception(s)), the claim is patent-eligible, and the analysis is complete.

II. How To Analyze “Significantly Different”

If the claim recites or involves a judicial exception, such as a law of nature/natural principle or natural phenomenon (e.g., the law of gravity, F=ma, sunlight, barometric pressure, etc.), and/or something that appears to be a natural product (e.g., a citrus fruit, uranium metal, nucleic acid, protein, etc.), then the claim only qualifies as eligible subject matter if the claim as a whole recites something significantly different than the judicial exception itself. A significant difference can be shown in multiple ways, such as: (1) the claim includes elements or steps in addition to the judicial exception that practically apply the judicial exception in a significant way, e.g., by adding significantly more to the judicial exception; and/or (2) the claim includes features or steps that demonstrate that the claimed subject matter is markedly different from what exists in nature (and thus not a judicial exception).

The following factors should be used to analyze the claim to assist in answering Question 3 for claims reciting or involving judicial exceptions other than abstract ideas.3 On balance, if the totality of the relevant factors weigh toward eligibility, the claim qualifies as eligible subject matter. If the totality of the relevant factors weighs against eligibility, the claim should be rejected. The examiner’s analysis should carefully consider every relevant factor and related evidence before making a conclusion. The determination of eligibility is not a single, simple determination, but is a conclusion reached by weighing the relevant factors, keeping in mind that the weight accorded each factor will vary based upon the facts of the application. This factor-based analysis, which requires consideration and subsequent weighing of multiple factors, is similar to the Wands factor-based analysis used to evaluate whether undue experimentation is required to make and use a particular claimed invention. See, e.g., MPEP 2164.01(a) for an explanation of the Wands analysis.

Many of these factors originate from past eligibility factors. However, not every factor will be relevant to every claim and, as such, need not be considered in every analysis. For example, for a claim drawn solely to a nucleic acid, factors b) through f) and h) through l) would not be relevant, because the claim does not contain any elements in addition to the nucleic acid. Eligibility of such a claim would therefore turn on an analysis of factors a) and g). These factors are not intended to be exclusive or exhaustive as the developing case law may generate additional factors over time.

Factors that weigh toward eligibility (significantly different):

a) Claim is a product claim reciting something that initially appears to be a natural product, but after analysis is determined to be non-naturally occurring and markedly different in structure from naturally occurring products.

b) Claim recites elements/steps in addition to the judicial exception(s) that impose meaningful limits on claim scope, i.e., the elements/steps narrow the scope of the claim so that others are not substantially foreclosed from using the judicial exception(s).

c) Claim recites elements/steps in addition to the judicial exception(s) that relate to the judicial exception in a significant way, i.e., the elements/steps are more than nominally, insignificantly, or tangentially related to the judicial exception(s).

d) Claim recites elements/steps in addition to the judicial exception(s) that do more than describe the judicial exception(s) with general instructions to apply or use the judicial exception(s).

e) Claim recites elements/steps in addition to the judicial exception(s) that include a particular machine or transformation of a particular article, where the particular machine/transformation implements one or more judicial exception(s) or integrates the judicial exception(s) into a particular practical application. (See MPEP 2106(II)(B)(1) for an explanation of the machine or transformation factors).

f) Claim recites one or more elements/steps in addition to the judicial exception(s) that add a feature that is more than well-understood, purely conventional or routine in the relevant field.

Factors that weigh against eligibility (not significantly different):

g) Claim is a product claim reciting something that appears to be a natural product that is not markedly different in structure from naturally occurring products.

h) Claim recites elements/steps in addition to the judicial exception(s) at a high level of generality such that substantially all practical applications of the judicial exception(s) are covered.

i) Claim recites elements/steps in addition to the judicial exception(s) that must be used/taken by others to apply the judicial exception(s).

j) Claim recites elements/steps in addition to the judicial exception(s) that are well-understood, purely conventional or routine in the relevant field.

k) Claim recites elements/steps in addition to the judicial exception(s) that are insignificant extra-solution activity, e.g., are merely appended to the judicial exception(s).

l) Claim recites elements/steps in addition to the judicial exception(s) that amount to nothing more than a mere field of use.

Factors a) and g) concern the question of whether something that initially appears to be a natural product is in fact non-naturally occurring and markedly different from what exists in nature, i.e., from naturally occurring products. This question can be resolved by first identifying the differences between the recited product and naturally occurring products, and then evaluating whether the identified differences together rise to the level of a marked difference in structure. Not all differences rise to the level of marked differences, e.g., merely isolating a nucleic acid changes its structure (by breaking bonds) but that change does not create a marked difference in structure between the isolated nucleic acid and its naturally occurring counterpart. Myriad, 133 S. Ct. at 2116-2118 (even though an isolated gene is a non-naturally occurring fragment of chromosomal DNA, it is not markedly different from the chromosomal DNA because its nucleotide sequence has not been changed). Instead, a marked difference must be a significant difference, i.e., more than an incidental or trivial difference.

The fact that a marked difference came about as a result of routine activity or via human manipulation of natural processes does not prevent the marked difference from weighing in favor of patent eligibility. For example, cDNA having a nucleotide sequence that is markedly different from naturally occurring DNA is eligible subject matter, even though the process of making cDNA is routine in the biotechnology art. See id. at 2119. Similarly, a hybrid plant that is markedly different from naturally occurring plants is eligible subject matter, even though it was created via routine manipulation of natural processes such as pollination and fertilization. See, e.g., J.E.M. Ag Supply, Inc. v. Pioneer Hi-Bred Int’l, Inc., 534 U.S. 124, 145 (2001).

III. Examples

A. Composition/Manufacture Claim Reciting A Natural Product

Claim 1: A stable energy-generating plasmid, which provides a hydrocarbon degradative pathway.

Claim 2: A bacterium from the genus Pseudomonas containing therein at least two stable energy-generating plasmids, each of said plasmids providing a separate hydrocarbon degradative pathway.

ground: Stable energy-generating plasmids exist within certain bacteria in nature. Pseudomonas bacteria are naturally occurring bacteria. Naturally occurring Pseudomonas bacteria containing a stable energy-generating plasmid and capable of degrading a single type of hydrocarbon are known.

Analysis of Claim 1: The answer to Question 1 in the above analysis is “yes”, because the claim is to a plasmid, which is a composition of matter. The answer to Question 2 is “yes”, because the claim recites a plasmid that is naturally occurring, and thus the claim as a whole may be reciting nothing more than a natural product. After inquiring into the nature of the claimed invention by reviewing the specification and the record of the application, and by considering and weighing the relevant factors, the answer to Question 3 is determined to be “no”, because the claim as a whole recites something that is not significantly different than what exists in nature.

With respect to factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not satisfied, because there is no structural difference between the claimed plasmid and naturally occurring plasmids. Thus, the claimed plasmid is not markedly different from what exists in nature.

Factors b) through f) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the natural product.

With respect to factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is satisfied because the claimed plasmid is not markedly different from naturally occurring plasmids.

Factors h) through l) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the natural product.

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh against a significant difference. Accordingly, claim 1 does not qualify as eligible subject matter.

Analysis of Claim 2: The answer to Question 1 in the above analysis is “yes”, because the claim is to a manufacture or composition of matter. The answer to Question 2 is “maybe”, because the claim recites a Pseudomonas bacterium, which is naturally occurring, and thus the claim as a whole may be reciting nothing more than a natural product. While the claim recites limitations regarding the structure and function of the bacterium (e.g., the plasmids and the ability to degrade hydrocarbons), it is inappropriate to make a conclusory determination on the eligibility issue based on the mere recitation of these limitations in the claim. As a result, the analysis should proceed to Question 3.

After inquiring into the nature of the claimed invention by reviewing the specification and the record of the application, and by considering and weighing the relevant factors, the answer to Question 3 is determined to be “yes”, because the claim as a whole recites something significantly different than naturally occurring bacteria. Note that although the plasmids themselves are natural products, in claim 2 the recited “something that initially appears to be a natural product” that is analyzed under factors a) and g) is the bacterium containing the plasmids, and not the bacterium alone or the plasmids alone.

With respect to factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is satisfied because the claimed bacterium is markedly different, i.e., it is both structurally different (it was genetically modified to include more plasmids than are found in a single naturally occurring Pseudomonas bacterium) and functionally different (it is able to degrade at least two different hydrocarbons as compared to naturally occurring Pseudomonas bacteria that can only degrade a single hydrocarbon), and these structural and functional differences are significant enough to rise to the level of a marked difference.

Factors b) through f) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the bacterium.

With respect to factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is not satisfied because the claimed bacterium is markedly different.

Factors h) through l) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the bacterium.

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh toward a significant difference. Accordingly, claim 2 qualifies as eligible subject matter.

The above-claimed bacterium of claim 2 was held to be patent-eligible subject matter in Chakrabarty. Recently, the Supreme Court looked to this claim as an example of something that although similar to a natural product is nonetheless patent-eligible, because it is significantly different than naturally occurring bacteria, as explained in Myriad, 133 S. Ct. at 2116-17:

In Chakrabarty, scientists added four plasmids to a bacterium, which enabled it to break down various components of crude oil. 447 U. S., at 305, 100 S. Ct. 2204, 65 L. Ed. 2d 144, and n. 1. The Court held that the modified bacterium was patentable. It explained that the patent claim was “not to a hitherto unknown natural phenomenon, but to a nonnaturally occurring manufacture or composition of matter–a product of human ingenuity ‘having a distinctive name, character [and] use.’” Id., at 309-310, 100 S. Ct. 2204, 65 L. Ed. 2d 144 (quoting Hartranft v. Wiegmann, 121 U. S. 609, 615, 7 S. Ct. 1240, 30 L. Ed. 1012 (1887); alteration in original). The Chakrabarty bacterium was new “with markedly different characteristics from any found in nature,” 447 U. S., at 310, 100 S. Ct. 2204, 65 L. Ed. 2d 144, due to the additional plasmids and resultant “capacity for degrading oil.”

B. Composition vs. Method Claims, Each Reciting A Natural Product

Claim 1. Purified amazonic acid.

Claim 2. Purified 5-methyl amazonic acid.

Claim 3. A method of treating colon cancer, comprising:

administering a daily dose of purified amazonic acid to a patient suffering from colon cancer for a period of time from 10 days to 20 days,

wherein said daily dose comprises about 0.75 to about 1.25 teaspoons of amazonic acid.

Background: The Amazonian cherry tree is a naturally occurring tree that grows wild in the Amazon basin region of Brazil. The leaves of the Amazonian cherry tree contain a chemical that is useful in treating breast cancer, however, to be effective, a patient must eat 30 pounds of the leaves per day for at least four weeks. Many have tried and failed to isolate the cancer-fighting chemical from the leaves. Applicant has successfully purified the cancer-fighting chemical from the leaves and has named it amazonic acid. The purified amazonic acid is structurally identical to the amazonic acid in the leaves, but a patient only needs to eat one teaspoon of the purified acid to get the same effects as 30 pounds of the leaves. Applicant has discovered that amazonic acid is useful to treat colon cancer as well as breast cancer, and applicant has also created a derivative of amazonic acid in the laboratory (called 5-methyl amazonic acid), which is structurally different from amazonic acid and is functionally different, because it stimulates the growth of hair in addition to treating cancer.

Analysis of Claim 1: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a composition of matter, and because the claim recites a judicial exception, i.e., amazonic acid is a naturally occurring chemical found in the leaves of Amazonian cherry trees. The answer to Question 3 is “no”, because the claim as a whole does not recite something significantly different than the natural product, e.g., the claim does not include elements in addition to the judicial exception that add significantly more to the judicial exceptions, and also does not include features that demonstrate that the recited product is markedly different from what exists in nature.

With respect to factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not satisfied, because there is no structural difference between the purified acid in the claim and the acid in the leaves.

Factors b) through f) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the natural product.

With respect to factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is satisfied. The claim is a product claim reciting amazonic acid that is not markedly different from naturally occurring amazonic acid.

Factors h) through l) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the natural product, i.e., there is nothing in the claim other than the natural product.

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh against significantly different. Accordingly, claim 1 does not qualify as eligible subject matter.

Analysis of Claim 2: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a composition of matter, and because the claim recites (or may recite) a judicial exception, i.e., amazonic acid is a naturally occurring chemical found in the leaves of Amazonian cherry trees. The answer to Question 3 is “yes”, because the claim as a whole recites something significantly different than the natural product, e.g., the claim includes features that demonstrate that the recited product is markedly different from what exists in nature.

With respect to factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is satisfied. The 5-methyl amazonic acid is structurally different than naturally occurring amazonic acid (because of the addition of the 5-methyl group), and this structural difference has resulted in a functional difference (5-methyl amazonic acid stimulates the growth of hair in addition to treating cancer). While a functional difference is not necessary in order to find a marked difference, the presence of a functional difference resulting from the structural difference makes a stronger case that the structural difference is a marked difference. Therefore, 5-methyl amazonic acid is markedly different than naturally occurring amazonic acid.

Factors b) through f) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the acid.

With respect to factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is not satisfied. The claim is a product claim reciting an acid that is markedly different from what exists in nature.

Factors h) through l) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the acid.

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh toward significantly different. Accordingly, claim 2 qualifies as eligible subject matter.

Analysis of Claim 3: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a process, and because the claim recites a judicial exception, i.e., amazonic acid is a naturally occurring chemical found in the leaves of Amazonian cherry trees. The answer to Question 3 is “yes”, because the claim as a whole recites something significantly different than the natural product, e.g., the claim includes elements in addition to the judicial exception that add significantly more to the judicial exception.

With respect to factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor b) is satisfied. The step of administering a particular dosage of amazonic acid (0.75 to 1.25 teaspoons per day) for a particular length of time (10-20 days) to a particular patient (patient with colon cancer), meaningfully limits the scope of the claim to a particular application of amazonic acid. Because the specific dosage and treatment period limitations narrow the scope of the claim, others are not substantially foreclosed from using amazonic acid in other ways, e.g., to treat colon cancer at other dosages or for other lengths of time, to treat other cancers, etc.

Factor c) is satisfied. The administering step is significantly related to the judicial exception, because it is a step in which amazonic acid is manipulated in a particular and significant way.

Factor d) is satisfied. The administering step requires administration of a particular dosage of amazonic acid to a patient with colon cancer for a particular length of time, and thus is more than a general instruction to use amazonic acid.

Factor e) is not satisfied. There is no machine or transformation recited in the claim.

Factor f) is satisfied. Prior usage of Amazonian cherry tree leaves was for treatment of breast cancer patients. It was not well-known, routine or conventional to use amazonic acid (either isolated or in leaf form) to treat colon cancer, or in fact to treat any cancer at the recited dosage or for the recited length of treatment time.

With respect to factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is not applicable because the claim is not a product claim.

Factor h) is not satisfied, because the administering step is not recited at a high level of generality, but instead recites a specific dosage of amazonic acid to be administered for a specific time to a specific type of patient.

Factor i) is not satisfied. Amazonic acid can be applied in other ways, e.g., to treat colon cancer at other dosages or for other lengths of time, to treat other types of cancer, or in other compositions.

Factor j) is not satisfied. It was not well-known to use Amazonian cherry tree leaves or amazonic acid to treat colon cancer, or in fact to treat any cancer at the recited dosage or for the recited length of treatment time.

Factor k) is not satisfied. The administering step is not merely appended to the judicial exception, but instead is significantly related to the amazonic acid.

Factor l) is not satisfied. Administering a particular dosage of amazonic acid for a particular length of time is more than a mere field of use, because it limits the claim scope to a particular application of amazonic acid.

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh toward significantly different. Accordingly, claim 3 qualifies as eligible subject matter.

C. Manufacture Claim Reciting Natural Products

Claim: A fountain-style firework comprising: (a) a sparking composition, (b) calcium chloride, (c) gunpowder, (d) a cardboard body having a first compartment containing the sparking composition and the calcium chloride and a second compartment containing the gunpowder, and (e) a plastic ignition fuse having one end extending into the second compartment and the other end extending out of the cardboard body.

Analysis: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a manufacture, and because the claim recites judicial exceptions: calcium chloride, which is a naturally occurring mineral; and gunpowder, which is a mixture of naturally occurring saltpeter, sulfur and charcoal. The answer to Question 3 is also “yes”, because the claim as a whole recites something significantly different than the natural products by themselves, i.e., the claim includes elements in addition to calcium chloride and gunpowder (the sparking composition, cardboard body and ignition fuse) that amount to a specific practical application of the natural products.

With respect to the factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not satisfied, because the calcium chloride and gunpowder as recited in the claim are not markedly different from what exists in nature.

Factor b) is satisfied because the claimed elements in addition to the calcium chloride and gunpowder narrow the scope of the claim so that others are not foreclosed from using the natural products in other ways, e.g., others can still use calcium chloride in products such as concrete, foods, fire extinguishers, etc., and can still use gunpowder in other products such as rifle cartridges.

Factor c) is satisfied because the claimed elements relate to the calcium chloride and gunpowder in a significant way, e.g., the combination of the claimed elements forms a structure into which the calcium chloride and gunpowder are physically integrated. In other words, the claim is drawn to a combination of physically interrelated elements including the natural products.

Factor d) is satisfied because the claimed elements do more than describe the natural products with general instructions to use them, e.g., the claim as a whole recites a firework having multiple elements including calcium chloride and gunpowder, which in effect provides instructions about one specific application of calcium chloride and gunpowder.

Factor e) is not satisfied because no machine or transformation is recited.

Factor f) is not satisfied because a review of the specification and the record reveals that none of the additional elements adds a feature that is more than well-understood, purely conventional or routine in the firework art.

With respect to the factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is satisfied, because the claimed calcium chloride and gunpowder are not markedly different from what exists in nature.

Factor h) is not satisfied, because the claimed elements are not recited at a high level of generality, but instead are recited with specificity such that all substantial applications of the natural products are not covered. E.g., others can still use calcium chloride in products such as concrete, foods, fire extinguishers, etc., and can still use gunpowder in other products such as rifle cartridges.

Factor i) is not satisfied, because the claimed elements are not required to use calcium chloride or gunpowder, e.g., others can still use calcium chloride and gunpowder in other ways without the claimed elements such as the cardboard body and the ignition fuse.

Factor j) is satisfied, because the elements in addition to the natural products are well-understood, purely conventional, and routine in the firework art.

Factors k) and l) are not satisfied, because the claimed elements are a significant part of the claim (factor k), e.g., the combination of the claimed elements forms a structure into which the calcium chloride and gunpowder are physically integrated, and are substantial limitations that integrate the calcium chloride and gunpowder into a specific application as opposed to being mere fields of use (factor l).

When the relevant factors toward and against eligibility are balanced, the factors weigh toward a significant difference. Accordingly, the claim qualifies as eligible subject matter.

D. Composition Claim Reciting Multiple Natural Products

Claim: An inoculant for leguminous plants comprising a plurality of selected mutually non-inhibitive strains of different species of bacteria of the genus Rhizobium, said strains being unaffected by each other in respect to their ability to fix nitrogen in the leguminous plant for which they are specific.

Background: Rhizobium bacteria are naturally occurring bacteria that infect leguminous plants such as clover, alfalfa, beans and soy. After the bacteria become established in a plant host, they are able to fix nitrogen gas from the atmosphere into a different chemical form that is more reactive and usable by the plant host. Each species of bacteria will only infect certain types of plants, for example R. meliloti will only infect alfalfa and sweet clover, and R. phaseoli will only infect garden beans. It was assumed in the prior art that all Rhizobium species were mutually inhibitive, because prior art combinations of different bacterial species produced an inhibitory effect on each other when mixed together, with the result that their efficiency was reduced. Applicant has discovered that there are particular strains of each Rhizobium species that do not exert a mutually inhibitive effect on each other, and that these mutually non-inhibitive strains can be isolated and used in mixed cultures.

Analysis: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a composition of matter, and because the claim recites judicial exceptions, i.e., the bacterial strains are naturally occurring bacterial strains. The answer to Question 3 is “no”, because the claim as a whole does not recite something significantly different than the natural products, e.g., the claim does not include elements in addition to the judicial exceptions that add significantly more to the judicial exceptions, and also does not include features that demonstrate that the recited products are markedly different from what exists in nature.

With respect to factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not satisfied, because none of the natural products recited in the claim are markedly different. The specification describes that applicant has not changed the bacteria in any way, but instead has simply combined various strains of naturally occurring bacteria together. Because the bacteria are structurally identical to naturally occurring bacteria, they are not markedly different.

Factors b) through f) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the natural products, i.e., there is nothing in the claim other than the bacteria.

With respect to factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is satisfied, because none of the bacteria are markedly different, as described above with respect to factor a).

Factors h) through l) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the natural products, i.e., there is nothing in the claim other than the bacteria.

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh against significantly different. Accordingly, the claim does not qualify as eligible subject matter.

The above-claimed inoculant was held to be ineligible subject matter in Funk Brothers Seed Co. v. Kalo Inoculant Co., 333 U.S. 127, 131 (1948):

Discovery of the fact that certain strains of each species of these bacteria can be mixed without harmful effect to the properties of either is a discovery of their qualities of non-inhibition. It is no more than the discovery of some of the handiwork of nature and hence is not patentable. The aggregation of select strains of the several species into one product is an application of that newly-discovered natural principle. But however ingenious the discovery of that natural principle may have been, the application of it is hardly more than an advance in the packaging of the inoculants. Each of the species of root-nodule bacteria contained in the package infects the same group of leguminous plants which it always infected. No species acquires a different use. The combination of species produces no new bacteria, no change in the six species of bacteria, and no enlargement of the range of their utility. Each species has the same effect it always had. The bacteria perform in their natural way. Their use in combination does not improve in any way their natural functioning. They serve the ends nature originally provided and act quite independently of any effort of the patentee.

Recently, the Supreme Court looked to this claim as an example of ineligible subject matter, stating that “the composition was not patent eligible because the patent holder did not alter the bacteria in any way.” Myriad, 133 S. Ct. at 2117.

E. Composition vs. Method Claims, Each Reciting Two Natural Products

Claim 1. A pair of primers, the first primer having the sequence of SEQ ID NO: 1 and the second primer having the sequence of SEQ ID NO: 2.

Claim 2. A method of amplifying a target DNA sequence comprising:

providing a reaction mixture comprising a double-stranded target DNA, the pair of primers of claim 1, wherein:

the first primer is complementary to a sequence on the first strand of the target DNA and the second primer is complementary to a sequence on the second strand of the target DNA, Taq polymerase, and a plurality of free nucleotides comprising adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine;

heating the reaction mixture to a first predetermined temperature for a first predetermined time to separate the strands of the target DNA from each other;

cooling the reaction mixture to a second predetermined temperature for a second predetermined time under conditions to allow the first and second primers to hybridize with their complementary sequences on the first and second strands of the target DNA, and to allow the Taq polymerase to extend the primers; and

repeating steps (b) and (c) at least 20 times.

Analysis of Claim 1: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a composition of matter, and because the claim recites judicial exceptions, i.e., SEQ ID NOs: 1 and 2 are naturally occurring DNA sequences found on a human chromosome. The answer to Question 3 is “no”, because the claim as a whole does not recite something significantly different than the natural products, e.g., the claim does not include elements in addition to the judicial exceptions that add significantly more to the judicial exceptions, and also does not include features that demonstrate that the recited products are markedly different from what exists in nature.

With respect to factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not satisfied, because neither of the natural products recited in the claim is markedly different. The term “primer” has an ordinary meaning in the art as being an isolated nucleic acid that can be used as a starting point for DNA synthesis. Thus, the first and second primers are isolated nucleic acids. However, even though isolation structurally changes a nucleic acid from its natural state, the resultant difference (e.g., “broken” bonds) is not significant enough to render the isolated nucleic acid markedly different, because the genetic structure and sequence of the nucleic acid has not been altered. See, e.g., Myriad, 133 S. Ct. at 2116-18. Further, the first and second primers have the same function as their natural counterpart DNA, i.e., to hybridize to their complementary nucleotide sequences. The minor structural differences taken together with the lack of any functional difference between the primers and the natural DNA fail to demonstrate that the recited products are markedly different from what exists in nature.

Factors b) through f) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the natural products, i.e., there is nothing in the claim other than the two natural products.

With respect to factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is satisfied, because neither of the natural products are markedly different, for the reasons stated above with respect to factor a).

Factors h) through l) are not relevant, because the claim does not include any elements in addition to the natural products, i.e., there is nothing in the claim other than two natural products.

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh against significantly different. Accordingly, the claim does not qualify as eligible subject matter.

Analysis of Claim 2: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a process, and because the claim recites judicial exceptions, i.e., SEQ ID NOs: 1 and 2 are naturally occurring DNA sequences found on a human chromosome, Taq polymerase is a naturally occurring bacterial enzyme, and adenine, thymine, cytosine and guanine are naturally occurring chemicals. The answer to Question 3 is also “yes”, because the claim as a whole recites something significantly different than the natural products, i.e., the claim includes elements in addition to the judicial exceptions that amount to a practical application of the natural products.

In particular, these elements satisfy several factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor b) is satisfied, because the heating and cooling steps contain a number of limitations that narrow the scope of the claim, for example, the target DNA must be heated and cooled to predetermined temperatures for predetermined times over at least 20 cycles, so that the primers are able to hybridize to their complementary sequences and the bacterial Taq polymerase is able to extend the primers and make copies of the target DNA. These limitations are meaningful, because others are not substantially foreclosed from using the natural products in other ways, e.g., others may use the target DNA in other methods or compositions.

Factor c) is satisfied, because the steps relate to the natural products in a significant way, e.g., the heating and cooling steps involve direct manipulation of the natural products in a way that is more than insignificant or tangential.

Factor d) is satisfied because the claimed elements do more than describe the natural products with general instructions to apply or use them, e.g., the claim as a whole recites an application of a combination of natural products that is limited to amplification using Taq polymerase in thermal cycling.

Factor e) is not satisfied because no machine or transformation is recited.

Factor f) is not satisfied, because the heating and cooling steps are well-understood, purely conventional and routine in the nucleic acid amplification art. With respect to the factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor h) cannot be satisfied because the claimed steps are not recited at such a high level of generality that the claim covers substantially all practical applications of the judicial exceptions. For example, others can still apply and use the natural products in other methods, such as a method of treatment or even an amplification method that does not involve Taq polymerase or thermal cycling.

Factor i) cannot be satisfied because the claimed steps are not required to be used by everyone who applies or uses the natural products. In particular, even if others must use primers to amplify a target DNA, others are not required to use Taq polymerase or thermal cycling in order to use the target DNA or the nucleotides.

Factor j) is satisfied, because the heating and cooling steps are well-understood, purely conventional and routine in the nucleic acid amplification art.

Factor k) is not satisfied, because the heating and cooling steps involve direct manipulation of the natural products, and thus are not merely appended to the judicial exceptions.

Factor l) is not satisfied. The heating and cooling steps involve direct manipulation of the natural products and limit the claim scope to a particular use/application of the natural products (amplifying this particular target DNA).

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh toward significantly different. Accordingly, the claim qualifies as eligible subject matter.

F. Process Claim Involving A Natural Principle And Reciting Natural Products

Claim: A method for determining whether a human patient has degenerative disease X, comprising:

obtaining a blood sample from a human patient;

determining whether misfolded protein ABC is present in the blood sample, wherein said determining is

performed by contacting the blood sample with antibody XYZ and detecting whether binding occurs between misfolded protein ABC and antibody XYZ using flow cytometry, wherein antibody XYZ binds to an epitope that is present on misfolded protein ABC but not on normal protein ABC; and

diagnosing the patient as having degenerative disease X if misfolded protein ABC was determined to be present in the blood sample.

Analysis: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a process, and because the claim recites judicial exceptions, e.g., the correlation between the presence of misfolded protein ABC in blood and degenerative disease X is a natural principle, and the blood and protein ABC are both natural products. A review of the specification indicates that antibody XYZ does not exist in nature, and is not purely conventional or routine in the art (it was newly created by the inventors).

The answer to Question 3 is also “yes”, because the claim as a whole recites something significantly different than the natural principle, i.e., the claim includes elements in addition to the judicial exceptions (e.g., contacting the blood sample with antibody XYZ, and detecting binding using flow cytometry) that amount to a practical application of the natural principle.

In particular, these elements satisfy several factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor b) is satisfied, because the recitations of using antibody XYZ to bind to protein ABC and detecting the resultant binding using flow cytometry narrow the scope of the claim, so that others are not foreclosed from using other means to detect misfolded protein ABC in order to apply the correlation.

Factor c) is satisfied, because the elements relate to the natural principle in a significant way, e.g., determining whether misfolded protein ABC is present in the blood is directly connected to the correlation between misfolded protein ABC and degenerative disease X.

Factor d) is satisfied because the claimed elements do more than describe the natural principle with general instructions to apply it, e.g., the claim as a whole recites an application of the natural principle that is limited to the use of a particular antibody and a particular detection method.

Factor e) is not satisfied because no machine or transformation is recited.

Factor f) is satisfied, because the specification explains that antibody XYZ is more than well-understood, purely conventional or routine in the art. With respect to the factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor h) cannot be satisfied because the claimed elements are not recited at such a high level of generality that the claim covers substantially all practical applications of the judicial exception. For example, others can still apply and use the natural principle in other methods, such as a method of treatment or a method of assessing whether a particular treatment regimen has resulted in a decrease in the amount of misfolded protein ABC in a patient’s blood.

Factor i) cannot be satisfied because some of the claimed elements are not required to be used by everyone who applies the correlation. In particular, even though others must obtain a blood sample from a patient in order to detect misfolded protein ABC in the blood, others are not required to use antibody XYZ and flow cytometry to detect misfolded protein ABC in a blood sample. Instead, others could use a different antibody in flow cytometry, or could use a different method of detecting binding such as Western blotting or radioimmunoassay.

Factor j) is not satisfied, because while the general concept of using antibodies to bind and detect the presence of a protein using flow cytometry is routine and conventional, it is not routine and conventional to use this particular antibody XYZ (a newly created antibody) to bind and detect the presence of a protein.

Factors k) and l) cannot be satisfied because the steps are more than insignificant extra solution activity and fields of use, for the reasons stated above with respect to factors c) and d).

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh toward significantly different. Accordingly, the claim qualifies as eligible subject matter.

G. Process Claims Involving a Natural Principle

Claim 1. A method for treating a mood disorder in a human patient, the mood disorder associated with neuronal activity in the patient’s brain, comprising:

exposing the patient to sunlight, wherein the exposure to sunlight alters the neuronal activity in the patient’s brain and mitigates the mood disorder.

Claim 2. A method for treating a mood disorder in a human patient, the mood disorder associated with neuronal activity in the patient’s brain, comprising:

exposing the patient to a synthetic source of white light, wherein the exposure to white light alters the neuronal activity in the patient’s brain and mitigates the mood disorder.

Claim 3. A method for treating a mood disorder in a human patient, the mood disorder associated with neuronal activity in the patient’s brain, comprising:

providing a light source that emits white light;

filtering the ultra-violet (UV) rays from the white light; and

positioning the patient adjacent to the light source at a distance between 30-60 cm for a predetermined period ranging from 30-60 minutes to expose photosensitive regions of the patient’s brain to the filtered white light, wherein the exposure to the filtered white light alters the neuronal activity in the patient’s brain and mitigates the mood disorder.

Background: It is a well-documented natural principle that white light affects a person’s mood. Exposure to white light changes neuronal activity in the brain, which changes a person’s mood. Sunlight is a natural source of white light. It is well-understood, purely conventional and routine in the art of treating mood disorders to expose a person to white light in order to alter their neuronal activity and mitigate mood disorders.

Analysis of Claim 1: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a process, and because the claim recites judicial exceptions, e.g., the natural principle or phenomenon that white light affects human neuronal activity, and the natural phenomenon of sunlight. The answer to Question 3 is “no”, because the claim as a whole does not recite something significantly different than the natural principle and the natural phenomenon, i.e., the claim does not include elements or steps in addition to the judicial exceptions that amount to a practical application of the judicial exceptions.

With respect to the factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor b) is not satisfied, because the only step in addition to the judicial exceptions is the step of exposing a patient to sunlight, and this step is not a meaningful limit on the claim scope, in that it substantially forecloses others from using or applying sunlight (a natural phenomenon) alone or in connection with the natural principle.

Factor c) is satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to sunlight integrates the natural principle into the claim in a way that is more than insignificant or tangential.

Factor d) is not satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to sunlight is no more than a general instruction to apply or use the natural principle and natural phenomenon.

Factor e) is not satisfied because no machine or transformation is recited.

Factor f) is not satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to sunlight is well-understood, purely conventional and routine in the art of treating mood disorders. With respect to the factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor h) is satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient is recited at a high level of generality and the claim covers substantially all practical applications of using sunlight (a natural phenomenon) in combination with the natural principle that white light affects human neuronal activity.

Factor i) is satisfied with respect to sunlight, because in order to use or apply sunlight, a person or thing must be exposed to it. However, factor i) is not satisfied with respect to the natural principle that white light affects human neuronal activity, because a person could be exposed to an artificial source of white light instead.

Factor j) is satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to sunlight is well-understood, purely conventional and routine in the art of treating mood disorders.

Factor k) is not satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to sunlight integrates the natural principle into the claim and thus is more than extra-solution activity.

Factor l) is satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to sunlight is a mere field of use with respect to the sunlight (it is an attempt to limit applications of sunlight to the field of mood disorder treatment) and with respect to the natural principle (it is an attempt to limit applications of the principle to the technological environment of sunlight as opposed to artificial light).

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh against significantly different. Accordingly, the claim does not qualify as eligible subject matter.

Analysis of Claim 2: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a process, and because the claim recites a judicial exception, e.g., the natural principle or phenomenon that white light affects human neuronal activity. The answer to Question 3 is “no”, because the claim as a whole does not recite something significantly different than the natural principle, i.e., the claim does not include elements or steps in addition to the judicial exception that amount to a practical application of the judicial exception.

With respect to the factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor b) is satisfied, because the step of exposing a person to a synthetic source of white light meaningfully limits the claim, because others are not substantially foreclosed from using or applying the natural principle in other ways, e.g., by exposing a person to sunlight instead of synthetic light.

Factor c) is satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to white light integrates the natural principle into the claim in a way that is more than insignificant or tangential.

Factor d) is not satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to white light is no more than a general instruction to apply or use the natural principle.

Factor e) is not satisfied because no machine or transformation is recited.

Factor f) is not satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to white light is well-understood, purely conventional or routine in the art of treating mood disorders. With respect to the factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor h) is satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient is recited at a high level of generality and the claim covers substantially all practical applications of using white light in combination with the natural principle that white light affects human neuronal activity.

Factor i) is not satisfied with respect to the natural principle that white light affects human neuronal activity, because a person could be exposed to sunlight instead of artificial white light.

Factor j) is satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to white light is well-understood, purely conventional or routine in the art of treating mood disorders.

Factor k) is not satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to white light integrates the natural principle into the claim and thus is more than extra-solution activity.

Factor l) is satisfied, because the step of exposing a patient to synthetic white light for the purpose of affecting a mood disorder is just an attempt to limit the use of the natural principle to a particular technological environment (use of artificial light as opposed to sunlight).

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh against significantly different. Accordingly, the claim does not qualify as eligible subject matter.

Analysis of Claim 3: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a process, and because the claim recites a judicial exception, e.g., the natural principle or phenomenon that white light affects human neuronal activity. The answer to Question 3 is “yes”, because the claim as a whole recites something significantly different than the natural principle, i.e., the claim includes elements or steps in addition to the judicial exception that amount to a practical application of the judicial exception.

With respect to the factors weighing toward eligibility:

Factor a) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor b) is satisfied, because the filtering and positioning steps meaningfully limit the claim to a particular application of the natural principle. Others are not substantially foreclosed from using or applying the natural principle in other ways, e.g., by exposing a patient to sunlight, by positioning the patient for a different length of time or at a different distance, etc.

Factor c) is satisfied, because the filtering and positioning steps are significantly related to the natural principle in that the filtering step manipulates the white light and the positioning step specifies how the patient is exposed to the white light.

Factor d) is satisfied, because the filtering and positioning steps are more than general instructions to apply or use the natural principle.

Factor e) is not satisfied because no machine or transformation is recited.

Factor f) is satisfied, because it is not well-understood, purely conventional or routine in the art of treating mood disorders to position a patient at the recited distance from a filtered light source for the recited length of time.

With respect to the factors weighing against eligibility:

Factor g) is not relevant, because the claim is a process claim, not a product claim.

Factor h) is not satisfied, because the filtering and positioning steps are not recited at such a high level of generality that they cover substantially all practical applications of the principle.

Factor i) is not satisfied, because a person could be exposed to sunlight instead of filtered white light, and could be positioned at a different distance or for a different length of time.

Factor j) is not satisfied, because it is not well-understood, purely conventional or routine in the art of treating mood disorders to position a patient at the recited distance from a filtered light source for the recited length of time.

Factor k) is not satisfied, because the filtering and positioning steps integrate the natural principle into the claim and thus are more than extra-solution activity.

Factor l) is not satisfied, because the filtering and positioning steps represent a specific practical application of the natural principle that is more than a mere field of use.

In sum, when the relevant factors are analyzed, they weigh toward significantly different. Accordingly, the claim qualifies as eligible subject matter.

H. Process Claim Reciting An Abstract Idea and a Natural Product

Claim: A method for identifying a mutant BRCA2 nucleotide sequence in a suspected mutant BRCA2 allele which comprises comparing the nucleotide sequence of the suspected mutant BRCA2 allele with the wild-type BRCA2 nucleotide sequence, wherein a difference between the suspected mutant and the wild-type sequences identifies a mutant BRCA2 nucleotide sequence.

Analysis: The answers to Questions 1-2 in the above analysis are both “yes”, because the claim is to a process, and because the claim recites judicial exceptions, e.g., the claimed comparing (the only step in the claim) is an abstract idea, and the recited “wild-type BRCA2 nucleotide sequence” is a natural product. Because the claim recites an abstract idea, Question 3 should be analyzed using only the existing guidance in MPEP § 2106(II). Note that MPEP § 2106(II) includes guidance about how the practical application of another judicial exception (such as a law of nature) affects the eligibility analysis of a claim that recites an abstract idea, e.g., in MPEP § 2106(II)(B)(1)(c). Thus, even though the claim recites both an abstract idea and a natural product, the analysis in MPEP § 2106(II) will control whether the claim qualifies as eligible subject matter.

This particular claim (claim 1 of U.S. Patent No. 6,033,857) was held to be ineligible subject matter in Association for Molecular Pathology v. Myriad Genetics, Inc., 689 F.3d 1303, 1333-35 (Fed. Cir. 2012), aff’d in part and rev’d in part on other grounds, 569 U.S. __, 133 S. Ct. 2107, 2116 (2013), because the court held that the claimed comparing was an abstract mental process.

IV. Form Paragraph

Revised form paragraph 7.05.13 should be used when rejecting claims (machine, composition, manufacture, or process claims) that recite or involve a law of nature/natural principle, natural phenomenon, or natural product for lack of subject matter eligibility under 35 U.S.C. 101. This form paragraph must be preceded by form paragraphs 7.04 and 7.05.

¶ 7.05.13 Rejection, 35 U.S.C. 101, Non-Statutory (Law of Nature or Natural Phenomenon) [REVISED]

the claimed invention is not directed to patent eligible subject matter. Based upon an analysis with respect to the claim as a whole, claim(s) [1] do not recite something significantly different than a judicial exception. The rationale for this determination is explained below: [2]

Examiner Note:

-

This form paragraph should be used when rejecting claim(s) that have a law of nature/natural principle or a natural phenomenon, e.g., a natural product, as a claim limitation.

-

In bracket 2, identify the judicial exception(s) that is/are recited or involved in the claim, and explain why the features (e.g., element(s) or step(s) in addition to the judicial exception(s)) in the claim do not result in the claim as a whole reciting something significantly different than the judicial exception itself. In particular, explain why the claim features do not add significantly more to the judicial exception and/or demonstrate that the judicial exception is in fact markedly different from what exists in nature. For instance, element(s) or step(s) in addition to the judicial exception can be shown to be extra-solution activity or mere field of use that impose no meaningful limit on the performance of a claimed method, or can be shown to be no more than well-understood, purely conventional, and routinely taken by others in order to apply the judicial exception. The explanation needs to be sufficient to establish a prima facie case of patent ineligibility under 35 U.S.C. 101.