Fair use lets courts “avoid rigid application of the copyright statute when, on occasion, it would stifle the very creativity which that law is designed to foster.” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, 510 U.S. 569, 581 (1994).

Fair use is a flexible standard. There are no safe harbors or bright line rules. This is both a bug and a feature. It is very difficult to know in advance whether a remix or new work will be considered fair use. On the other hand, there are no strict rules prohibiting certain types of copying. Many types of new and interesting art is potentially fair use.

This post is a bit more technical, and includes cites to the relevant supreme court cases. If you have a question about “is this [specific copying] fair use?” then you have come to the wrong place. There are no easy answers here.

If you want a rapid fire list of what’s fair use and what’s not (in visual art), then check out this post on Fair Use Illustrated in Appropriation Art

Contents:

Summary of Fair Use Factors

Fair use, codified in §107 of the Copyright Act, is a flexible standard, not a bright-line rule. Borrowing a small amount of an existing work tends to be fair use, but there is no fixed threshold that guarantees fair use. We can’t say, for example, that using less than 10% of a film or poem is always fair use. Instead, fair use balances several factors, summarized below:

| Fair Use | Infringement | |

| Purpose: | teaching | commercial |

| research & scholarship | entertainment | |

| criticism | bad-faith behavior or intent | |

| comment | plagiarism, not crediting original author | |

| news reporting | ||

| transforming parts of original work into new and productive uses | ||

| parody | ||

| Nature: | copying from a published Work | copying from an unpublished work |

| copying from a factual work | copying from a creative work | |

| Amount: | small quantity | large quantity or entire work copied |

| appropriate quantity for purpose of new work | copied “heart of the work” | |

| copied portion was not central to original work | ||

| Effect: | copying from a lawfully purchased version of the work. | copied from a stolen version of the original work |

| very few copies of the new work made or sold | many copies made or sold | |

| no significant effect on the potential market for the original work | copied work competes with original work, or otherwise affects the market for the original | |

| no licensing mechanism / licensing would be inefficient or impossible |

Principles of Fair Use

The 1976 Copyright Act incorporated the judicial doctrine of fair use into the statute. It provides illustrative fair use examples and a four factor test. But courts are not limited to these four factors. They may consider any relevant information. Section 107 provides:

Notwithstanding the provisions of § 106, the fair use of a copyrighted work, including such use by reproduction in copies or phonorecords or by any other means specified by that section, for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research, is not an infringement of copyright. In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. The fact that a work is unpublished shall not of itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

The final sentence, reducing the significance of copying from an unpublished work, was added in 1992 in response to cases involving historians’ use of unpublished letters and diaries.

Fair Use Flexibility

The fair use clause of § 107 provides flexible guidance. It endorses the purpose and general scope of the judicial fair use doctrine, “but there is no disposition to freeze the doctrine in the statute, especially during a period of rapid technological change… The courts must be free to adapt the doctrine to particular situations on a case-by-case basis. Section 107 is intended to restate the present judicial doctrine of fair use, not to change, narrow, or enlarge it in any way.” H.R. Rep. No. 94-1476, at 66 (1976).

The first two Supreme Court cases to construe § 107 illustrate its flexibility. In the Betamax case, the Supreme Court found that taping a copyrighted TV show to watch later (“time-shifting”) was fair use. Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417 (1984). Time-shifting is not a statutory fair-use purpose. Section 107 lists: criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, and research. Even though time-shifting is not an enumerated fair-use purpose, and even though consumers were copying entire TV shows, the Supreme Court found fair use.

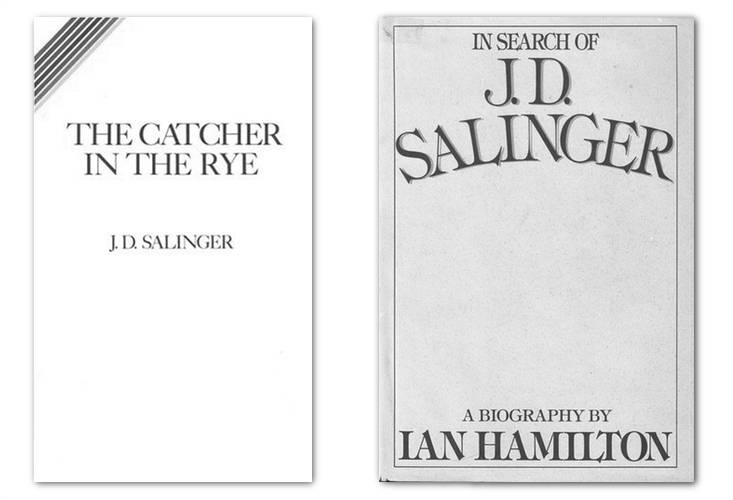

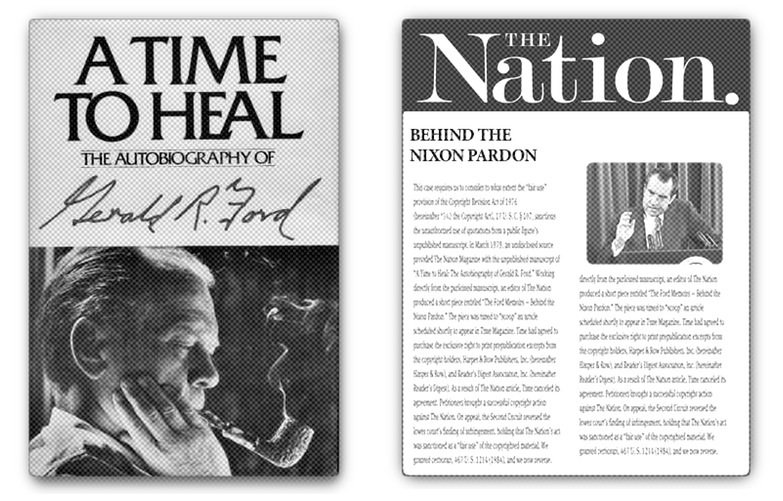

The fair use provision lists several examples of prototypical fair use: “the fair use of a copyrighted work… for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting… is not an infringement.” In the Ford Memoirs case, the Supreme Court refused to allow fair use, even for the use of 300 words for the purposes of criticism, comment and news reporting. Harper & Row v. Nation, 471 U.S. 539 (1985). Harper & Row sued the Nation magazine for quoting a single paragraph from the soon-to-be-published memoirs of President Ford. The Nation was quite plausibly engaged in criticism, comment and newsreporting–all statutory fair-use purposes. Although only a few lines were copied, they were the lines about Ford’s pardon of Nixon–the heart of the memoir.

In explaining the weight to be given to the listing of uses in the first sentence of § 107, the Court in Harper & Row stated that the enumeration “give[s] some idea of the sort of activities the courts might regard as fair use under the circumstances…. This listing was not intended to be exhaustive… or to single out any particular use as presumptively a ‘fair’ use.” Id. at 561. The Court emphasized that fair use “will depend upon the application of the determinative factors, including those mentioned in the second sentence.” Harper & Row v. Nation, 471 U.S. 539, 561 (1985).

Although the fair use test is flexible, courts must consider the four statutory factors. They are mandatory because the statute states that a fair use analysis “shall include” their consideration. Pacific & S. Co. v. Duncan, 744 F.2d 1490 (11th Cir. 1984). See also, Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, 510 U.S. 569 (1994) (“Parody, like any other use, has to work its way through the relevant factors, and be judged case by case, in light of the ends of the copyright law.”).

Supreme Court Fair Use Decisions

Despite some initial inconsistencies, the Supreme Court has come to provide intelligible and useful guidelines for fair use analysis.

Personal, Noncommercial Use: Betamax Case

In the 1984 Betamax case, the Supreme Court reviewed the statutory fair use factors and found, in a 5-4 decision, that recording TV shows to watch later was fair use. Sony Corp. of America v. Universal City Studios, Inc., 464 U.S. 417 (1984). The Court called this type of home recording “time-shifting.” The first factor supported fair use because the home viewer taped the program for personal and noncommercial use. The Court majority in fact announced that “every commercial use of copyrighted material is presumptively an unfair [use]” and also presumptively demonstrates a likelihood of economic harm to the copyright owner (the fourth statutory factor); “but if [the copying] is for a noncommercial purpose, the likelihood must be demonstrated.” Id. at 451.

The Court acknowledged that, even though typically the entire program was taped (the third factor), this was not particularly damaging to the fair use contention because the program had in any event been broadcast free to the public. Finally, upon examination of the factual record, the Court concluded that there was inadequate evidence that home taping for time-shifting purposes would have any material adverse impact upon the market for the plaintiffs’ programming, either in its initial exhibition or in later exhibition on television (reruns) or even potentially in motion picture theaters. The four dissenters strongly disagreed with respect to the application and conclusion of the four-factor analysis.

Stolen Memoirs: Not Fair Use

The Court divided again (6 to 3) the following year in Harper & Row v. Nation, 471 U.S. 539 (1985). In Harper & Row, the publisher of The Nation magazine secured a purloined copy President Ford’s soon-to-be-published memoirs. The Nation published its story about the Ford pardon of Nixon, quoting some 300 words from the unpublished manuscript.

…Nixon had repeatedly assured me that he was not involved in Watergate, that the evidence would prove his innocence…

Harper & Row was not excited to be scooped in the publication of their own book. They sued. The Court traced the development of the fair use doctrine and noted its nearly nonexistent application to unpublished works under prior copyright law. It rejected the defendant’s claim that First Amendment concerns warranted contracting the scope of copyright and concluded, instead, that First Amendment interests are already protected under copyright doctrines such as fair use and the idea–expression dichotomy. The Court also rejected the contention that works of public figures are entitled to lesser copyright protection, and ruled against fair use.

The Supreme Court acknowledged that The Nation was engaged in news reporting, one of the enumerated fair use purposes of § 107. But the Court invoked the Sony presumption against commercial uses. The Nation–as defendant–had the burden of proving its use was fair use (typically by showing no adverse market impact upon the plaintiff’s work). As to the second statutory factor, the Court conceded that “the law generally recognizes a greater need to disseminate factual works than works of fiction or fantasy.” Id. at 563. But the Court concluded that The Nation had copied more than merely objective facts. Moreover, “the fact that a work is unpublished is a critical element of its ‘nature’,” Id. at 564. This is a “key, though not necessarily determinative factor” against fair use. Id. at 554. Although a relatively small part of the Ford manuscript was copied, it comprised a large part of the article in The Nation and, most significantly, was qualitatively among the most important parts of the manuscript, containing the “most powerful passages,” the “dramatic focal points” of great “expressive value.” The Court characterized the fourth statutory factor—effect upon the potential market for the copyrighted work—as “undoubtedly the single most important element of fair use.” Id. at 566. It pointed out that the “scooping” by The Nation caused Time to cancel its contract with Harper & Row to publish excerpts. Moreover, “[t]his inquiry must take account not only of harm to the original but also of harm to the market for derivative works,” Id. at 568, for the statute refers to adverse effect upon the “potential market” for the work.

Thus, after Sony and Nation, it appeared that there would be a compelling case against fair use should the record show a commercial use by the defendant, or a potentially significant adverse economic impact on the copyrighted work, or an unpublished copyrighted work.

After the Ford Memoirs case, courts were extremely reluctant to find fair use in unpublished material. See e.g., Salinger v. Random House, Inc., 811 F.2d 90 (2d Cir. 1987). compare, New Era Pubs. Int’l v. Henry Holt & Co., 873 F.2d 576 (2d Cir.), with New Era Pubs. Int’l v. Carol Publ’g Group, 904 F.2d 152 (2d Cir. 1990). Congress stepped in in 1992 to amend §107, adding: “The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.”

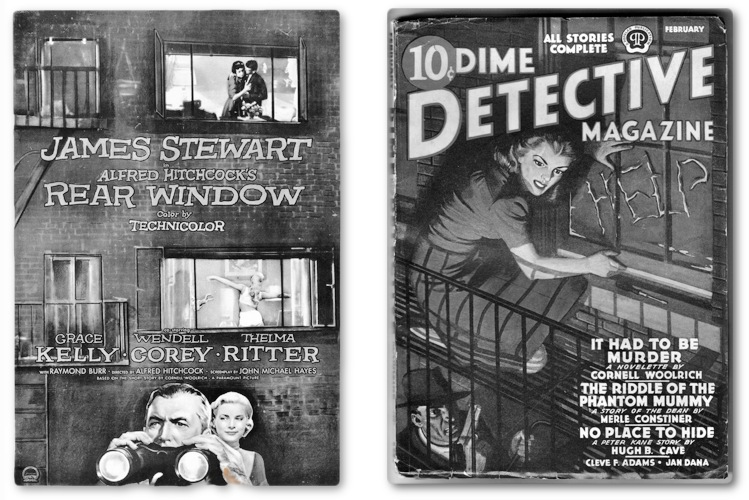

Hitchcock Film: Not Fair Use of a Short Story

The 1990 Rear Window case mainly discusses the renewal rights and derivative works. But it also includes a brief discussion of fair use. The Supreme Court found that Alfred Hitchcocks’s film Rear Window was not a fair use of the Cornell Woolrich story It Had to Be Murder. Stewart v. Abend, 495 U.S. 207 (1990). “[A]ll four factors point to unfair use. ‘This case presents a classic example of an unfair use: a commercial use of a fictional story that adversely affects the story owner’s adaptation rights.’” Id.

Parody and Fair Use: Campbell v. Acuff-Rose

In the Pretty Woman Parody case, Supreme Court clarified some fair use misconceptions, and established useful guidelines. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose Music, Inc., 510 U.S. 569 (1994). In Campbell, the hip-hop artists 2 Live Crew asked Acuff-Rose for permission to sample Roy Orbison’s “Pretty Woman.” Acuff-Rose denied, and 2 Live Crew sampled anyway, borrowing the distinctive opening guitar pattern, mimicking the opening “Pretty Woman” phrase in each verse. But they didn’t copy everything. 2 Live Crew added their own lyrics. The court of appeals found no fair use, relying heavily upon what clearly appeared to be the Supreme Court cases strongly disfavoring commercial uses and the copying of the “heart” of a copyrighted work.

The Supreme Court unanimously reversed. It held that parody— poking fun at an earlier copyright-protected work, as distinguished from poking fun at some extrinsic happening or individual (satire)—is a form of “criticism or comment”–one of the enumerated fair-use purposes of § 107. The four fair use factors must not “be treated in isolation, one from another. All are to be explored, and the results weighed together, in light of the purposes of copyright.” Id. at 578. The Court, through Justice Souter, gave credit to Justice Story, and Folsom v. Marsh, 9 F. Cas. 342 (C.C.D. Mass. 1841) for fashioning decisional criteria that were essentially incorporated by Congress in § 107 nearly 150 years later. In examining the first factor, the Court downgraded the importance of the defendants’ “commercial use,” noting that essentially all fair use claims (and the uses enumerated in the first sentence) are made in the for-profit context of publishing and broadcasting. The key issue is whether the defendant has made a “transformative” use: not one that merely supersedes the objects of the earlier work by copying it, but that “adds something new, with a further purpose or different character, altering the first with new expression, meaning, or message.” Id. at 579. A court must inquire “whether a parodic character may reasonably be perceived,” and no attention should be given to whether it is in good or bad taste (an issue that had been mooted in earlier decisions in the lower courts). As to the second factor, a court must determine whether the copyrighted work falls close “to the core of intended copyright protection” because it is creative (rather than essentially factual): the exemplar “Oh, Pretty Woman” was said to do so. The court of appeals had emphasized the third factor, and the taking of the qualitative “heart” of that song, but the Supreme Court—although it acknowledged that “quality and importance” of the copied material should count as well as quantity—observed that the lower court had failed to take account of the special nature of parody. “When parody takes aim at a particular original work, the parody must be able to ‘conjure up’ at least enough of that original to make the object of its critical wit recognizable…. [T]he heart is… what most readily conjures up the song for parody, and it is the heart at which parody takes aim. Copying does not become excessive in relation to parodic purpose merely because the portion taken was the original’s heart.” Id. at 588.

As for the fourth factor, and any adverse market impact that was to be “presumed” under Sony by virtue of the defendants’ commercial use, the Campbell decision significantly altered the standard: A presumption of market harm is not applicable to a case involving something beyond “verbatim copying of the original in its entirety,” Id. at 591, and thus not to a “transformative” work, particularly for a parody which serves a “different market function.” The Court remanded to allow the lower court to consider further evidence of market harm (flowing from rap-music substitution and not from parodic criticism), the amount of copyrighted material taken and what the defendants added to it, and other elements noted by the Court in its opinion.

With its decision in Campbell, the Supreme Court on the one hand diluted the helpful litigative presumptions of the earlier cases and emphasized the complementary and interactive nature of the four statutory factors, but pointed toward the “transformative” standard and potential adverse market harm as of central importance to fair use analysis. The Court also noted that in cases of parody and other critical works, in which there is infringement, and a fair use defense is found unpersuasive, an injunction need not automatically issue; the public’s interest in the publication of the later work and the interest of the copyright owner may both be protected by an award of damages.

Four-Factor Fair Use Test

Section 107 of the copyright act provides for fair use of copyrighted works. Unlicensed copying is more likely to be fair use “for purposes such as criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching (including multiple copies for classroom use), scholarship, or research…” § 107.

In determining whether the use made of a work in any particular case is a fair use the factors to be considered shall include—

- the purpose and character of the use, including whether such use is of a commercial nature or is for nonprofit educational purposes;

- the nature of the copyrighted work;

- the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole; and

- the effect of the use upon the potential market for or value of the copyrighted work. Copyright Act § 107.

1. Purpose and Character of Use

To decide whether the fair use doctrine applies, courts consider the “purpose and character” of the unlicensed use. A work’s commercial nature weighs against fair use. A work’s “nonprofit educational” nature weighs in favor of fair use.

Although the enumerated uses in the fair use clause (criticism, comment, news reporting, teaching, scholarship, or research) are not dispositive–not even presumptive–they play an important role in application of the first factor, the “purpose and character of the use.” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, 510 U.S. 569, 581 (1994).

Productive or Transformative Uses

A “transformative” use tends to weigh in favor of fair use. As Judge Leval put it:

“…if the quoted matter is used as raw material, transformed in the creation of new information, new aesthetics, new insights and understandings – this is the very type of activity that the fair use doctrine intends to protect for the enrichment of society.” Toward a Fair Use Standard, 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1105 (1990)

I have some further thoughts and comparisons on transformative uses in this post on Fair Use Illustrated in Appropriation Art.

Commercial or Non-Profit?

As the Supreme Court put it, the crux of the profit/nonprofit distinction is whether the user stands to profit from the use without paying the customary price.

“The crux of the profit/nonprofit distinction is not whether the sole motive of the use is monetary gain but whether the user stands to profit from exploitation of the copyrighted material without paying the customary price.

Harper & Row v. Nation, 471 U.S. 539, 562 (1985)

The commercial/nonprofit distinction is just one factor in a multi-factor standard. It is not dispositive, despite what strong language from the Supreme Court in Sony might suggest:

“every commercial use of copyrighted material is presumptively an unfair exploitation of the monopoly privilege that belongs to the owner of the copyright….”

Sony v. Universal City Studios, 464 U.S. 417, 451 (1984).

This “presumptively unfair” language was tempered the following year in Harper & Row v. Nation:

The fact that a publication was commercial as opposed to nonprofit is a separate factor that tends to weigh against a finding of fair use. “[E]very commercial use of copyrighted material is presumptively an unfair exploitation of the monopoly privilege that belongs to the owner of the copyright.”

Harper & Row v. Nation, 471 U.S. 539 (1985) & Row v. Nation, 471 U.S. 539, 562 (1985) (citing Sony)(emphasis added).

In Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, the Supreme Court overturned the 6th Circuit for “inflating the significance” of the Sony “presumption” against fair use for commercial works.

In giving virtually dispositive weight to the commercial nature of the [work], the Court of Appeals erred.

Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, 510 U.S. 569, 584 (1994).

2. Nature of the Copyrighted Work

The “nature of the copyrighted work” encompasses 2 separate issues. (1) Whether the work is expressive or creative, like a work of fiction, or whether it is more factual. Copying from a factual work weighs in favor of fair use. (2) Whether the copied work is published or unpublished. Copying from an unpublished work weighs heavily against fair use. Blanch v. Koons, 467 F.3d 244 (2006)(citing, 2 Howard B. Abrams, The Law of Copyright, § 15:52 (2006)).

Creative/Expressive vs. Factual?

Creative works are closer to the core of copyright protection than factual works. Its harder to establish fair use when the copied works are close to the creative core of copyright law. Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, 510 US 569 (1994). On the other hand, fair use is more likely when the original work is factual in nature.

[T]he more creative a work, the more protection it should be accorded from copying; correlatively, the more informational or functional the plaintiff’s work, the broader should be the scope of the fair use defense. Leadsinger, Inc. v. BMG Music Pub., 512 F. 3d 522 (9th Circuit 2008)(Citing 4 Nimmer on Copyright § 13.05[A][2][a]).

Between the purely-creative and purely-factual, there is a spectrum of works.

[E]ven within the field of fact works, there are gradations as to the relative proportion of fact and fancy. One may move from sparsely embellished maps and directories to elegantly written biography. The extent to which one must permit expressive language to be copied, in order to assure dissemination of the underlying facts, will thus vary from case to case.

Harper & Row v. Nation, 471 U.S. 539 (1985) (quoting, Gorman, Fact or Fancy? The Implications for Copyright, 29 J. Copyright Soc. 560, 561 (1982).

Parody. In parody cases, the distinction between expressive and factual works carries little weight. In fact, it is never “likely to help much in separating the fair use sheep from the infringing goats in a parody case, since parodies almost invariably copy publicly known, expressive works.” Campbell v. Acuff-Rose, 510 U.S. 569, 586 (1994).

Published or Unpublished

Use of an unpublished work weighs against fair use. But take pre-1992 cases with a grain of salt. In 1992, Congress amended the Copyright Act to add:

The fact that a work is unpublished shall not itself bar a finding of fair use if such finding is made upon consideration of all the above factors.

Copyright Act §107.

3. Amount and Substantiality of the Portion Used

The third fair use factor is “the amount and substantiality of the portion used in relation to the copyrighted work as a whole. Copyright Act §107.

Note that copyright law uses the term “substantiality” in two separate contexts: (1) proving infringement, and (2) fair use. To prove infringement, a plaintiff must show that the copied work is “substantially similar” to the original work. In the fair use context, substantiality issue turns on whether the user copied a reasonable amount of the original work in view of (a) the purpose of the use and (b) the likelihood of market substitution. Peter Letterese & Assoc. v. World Inst. of Scient., 533 F. 3d 1287, fn 30 (11th Cir. 2008).

4. Effect of the Use upon the Potential market for the Copyrighted Work

“This last factor is undoubtedly the single most important element of fair use.” Harper & Row v. Nation, 471 U.S. 539 (1985).

In considering the market effect, copyright law tries to balance (a) the public benefit of allowing free use, against (b) the copyright owner’s economic interest in preventing unlicensed use. The less adverse effect that an alleged infringing use has on the copyright owner’s expectation of gain, the less public benefit need be shown to justify the use. MCA, Inc. v. Wilson, 677 F. 2d 180 (2nd Cir 1981).

Further Reading

Judge Leval’s seminal, Toward a Fair Use Standard, 103 Harv. L. Rev. 1105 (1990).

Prof. William Fisher III, Reconstructing the Fair Use Doctrine, 101 Harv. L.Rev. 1659 (1988).

Prof. Barton Beebe, An Empirical Study of U.S. Copyright Fair Use Opinions, 1978-2005. 156 U. Penn. L. Rev. 549 (2008).