When is a patent claim indefinite? Thats the question before The Supreme Court in today’s Nautilus v. Biosig arguments.

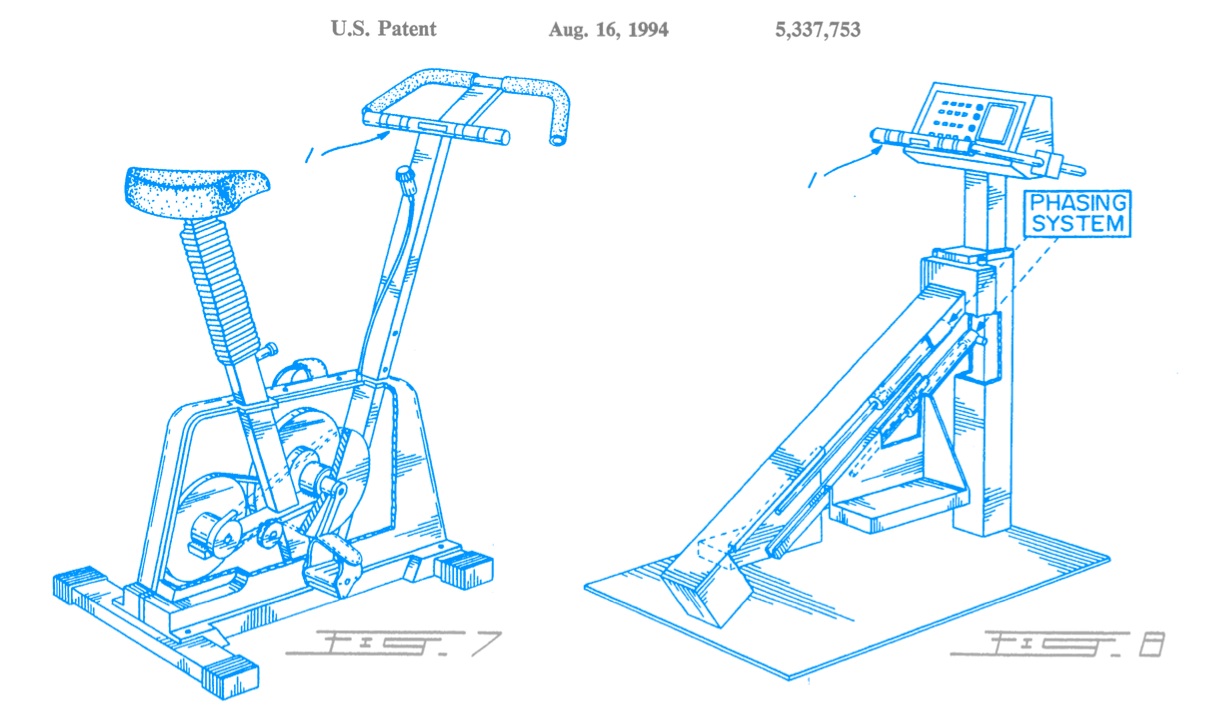

The patent involves exercise machines that measure heart rate. Nautilus sells these exercise machines, but doesn’t pay a license because it thinks Biosig’s patent claims are indefinite. The trial court agreed and invalidated BioSig’s patent. The Federal Circuit reversed, finding the claim was not “insolubly ambiguous” and therefore valid. This dispute, now 10 years old, has made its way up to the Supreme Court. Its a dispute over whether “spaced relationship” in the phrase below is indefinite:

“…a first live electrode and a first common electrode mounted on said first half in spaced relationship with each other…”

tl;dr? Here’s Mark Lemley’s tweet summary of the oral argument:

@Rachael_IP Insolubly ambiguous is going down, but likely to be replaced with something like the Chevron "zone of reasonableness" test.

— Mark Lemley (@marklemley) April 28, 2014

[ed. note: on June 2, 2014, the Supreme Court raised the standard to “Reasonable Certainty”]

Transcript below.

Monday, April 28, 2014

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: We’ll hear argument first this morning in Case 13369, Nautilus v. Biosig Instruments.

Mr. Vandenberg.

Oral Argument of John Vandenberg for Petitioner

MR. VANDENBERG: Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the Court.

The Patent Act requires particular and distinct claims, but the claim in this case is not particular and distinct. It is ambiguous because it has two reasonable readings with very different claim scopes, even after all of the interpretive tools are applied.

Such ambiguous claims defeat the public notice function which is at the heart of Section 112, and they increase litigation. They cause more claim construction disputes, and they cause more reversals of district court claim construction rulings.

Taken all together, ambiguous claims and the Federal circuit’s test allowing ambiguous claims defeats the very purpose of Section 112 and the patent system, namely, to encourage and promote innovation by others after the first patent issues.

JUSTICE GINSBURG: Why is this claim ambiguous? It’s evident that these electrodes have to be close enough so that the user’s hand contacts both electrodes, but separate enough to heap keep electrodes distinct. Why isn’t that sufficiently definite?

MR. VANDENBERG: Your Honor, if that were the only reasonable construction, then that may suffice. However, here, the other reasonable construction is that the spaced relationship is a special spacing that causes the electrodes to achieve the desired result. And that was the construction that the majority found at the Federal circuit, namely, that spaced relationship is not what it sounds like, namely, any spacing, but rather is a special spacing that is derived by trial-and-error testing to get the spacing just right so that the electrodes detect

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: I don’t think the majority or the concurrence or the other side disagreed with that. The only question was whether it was part of the specifications or not. I thought that was the only difference between them. They both agreed ultimately that the electrodes had to cancel out was it the EMGs?

MR. VANDENBERG: Correct.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: So they both agreed that that was part of the scope. The only issue was, was it part of the specifications or part of the claims. But both of them make up the scope of the patent.

MR. VANDENBERG: Your Honor, we would submit that the disagreements between the judges and, in fact, between Biosig itself went to the scope of the claim, namely, does the scope of the claim cover all ways of achieving the desired result no matter how the electrodes are spaced. That’s one possible reading.

The other possible reading is that the claims cover only a special spacing of the electrodes to achieve the desired result. And why that matters is if you think of the inventor in 1994 who invents a new material for electrodes, and this new material achieves the desired result of detecting equal muscle signals on the left and right side, regardless of the spacing of the electrode. So it doesn’t matter where you put the electrodes, as long as you can touch them, this new material achieved the the desired goal.

That inventor would not know in 1994 if they infringed or not, because if the claims had the interpretation that the majority eventually gave them, namely, that the spaced relationship has this functional limitation and it must be the result of this trial-and-error balancing, there’d be no infringement. But if spaced relationship meant any spacing, then there would be infringement. So that is the exact type of zone of uncertainty that United Carbon warned against and which deters the innovation.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: But it can’t mean any spacing, because anyone skilled in the art would know the hand has to cover it. So you’re basically talking about a fairly narrow range between one side of the hand and the other and not too close together that they don’t don’t work. And that seems to me that someone skilled in the art can just try a couple of things and see where where the trial and error. Trial and error makes could mean a very difficult thing, like Edison discovering what works in a light bulb. But here you’ve got a very limited range and someone skilled in the art will just, well, let’s try it, you know, close to the middle, let’s try it to so far apart. But it’s not any spaced relationship.

MR. VANDENBERG: And that’s correct, Your Honor, and I do when I refer to any spacing, it’s really a shorthand for any spacing that is narrow enough so that the hand can actually touch both electrodes but not touching. So I agree that under each interpretation it makes sense that the electrodes have to be touchable by a single hand, and they can’t be touching each other or there’d simply be a single electrode.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: What would be the purpose of the invention if it were only covering spacing without the function of canceling the EMG? I can’t understand, if I read this patent, what it would do unless you add its function.

MR. VANDENBERG: Well, Your Honor, the purpose of the patent is it would cover possibly, again, all techniques for achieving the desired function. So again, going back to the invention of the new material, if the inventor comes up with a specific way of achieving the result, and here they came up with trial and error spacing, they didn’t describe that in the patent. That didn’t that wasn’t described by the inventor until 15 years later. But nevertheless, let’s say they had this specific way of achieving it. They very well could have drafted the claim intentionally the way they did to have a broader coverage so that they cover all possible ways of achieving that desired result. Patent attorneys are trained to try to draft the claims, you know, some claims as broadly as possible. So that reading by the concurrence was a very plausible reading of this claim. Reading the claim, it has any spaced relationship as long as, as the Chief Justice indicated, I can touch them and they’re not touching each other. But that’s it. There’s no other restriction on what “spaced relationship” means. That’s a very reasonable interpretation and that was the interpretation that Biosig asserted at the Markman claim construction in this case.

JUSTICE SCALIA: But you you acknowledge that it it would be a valid patent if all you said is you have to space these things and you figure out what the spacing is going to be. You you can you can get a patent for tell somebody trial and error. Let’s take Edison’s light bulb. I mean, could he say, you know, get some material that that will will illumine when when electricity is passed through it and you figure out by trial and error what this material might be. Might be tungsten, who knows, you know. Maybe it’s chewing gum. Would that be a valid patent?

MR. VANDENBERG: It would not, Your Honor. That

JUSTICE SCALIA: So I don’t I don’t really understand this trial and error spacing stuff. What what is the limit on trial and error? Can you get patented anything when you say, you know, this is the basic principle, you figure out what you know, what makes it work.

MR. VANDENBERG: Well, Your Honor, there’s there’s two levels of indefiniteness here. First, it’s unclear which construction was intended. So basically, there are two reasonable

JUSTICE SCALIA: No. I understand that.

MR. VANDENBERG: But the second

JUSTICE SCALIA: I’m asking why the second construction is is a plausible patentable invention.

MR. VANDENBERG: Your Honor, it’s not patentable. In fact, it would be indefinite. However, the person of skill in the art reading the claim is not expected to do a fullblown invalidity analysis. They’re simply trying to figure out, where can I innovate. I see this patent. It issues in ‘94. The the alternative

JUSTICE SCALIA: All the person skilled in the art will know is that he has to figure out what the spacing is, right?

MR. VANDENBERG: No, Your Honor.

JUSTICE SCALIA: But but still the the inventor doesn’t tell you what the spacing has to be.

MR. VANDENBERG: Well, that is the second problem. We agree. The second problem with these claims is they’re purely functional. They simply have a clause that says whereby good things happen, namely, that equal muscle signals are detected. The claims don’t tell you how. They leave that up in the air. Maybe it has something to do with the spacing electrodes, but maybe not.

And the further problem is that the specification here did not describe any technique for achieving the desired result. If one reads the specification, you read it and it says various things and it says, whereby the muscle signals are detected as being equal on both hands, on both electrodes. Well, in reality, the the electrical signals on my left and right palms are unequal. Somehow, however, the electrodes detect them as if they’re being equal. The patent doesn’t say how. It doesn’t say why. It doesn’t say what causes it. So this is the purely functional type of claim that United Carbon and General Electric

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Do you do you have any disagreement with a standard that’s articulated by the Solicitor General? He says that, you know, a patent satisfies the requirement if, in light of the specification and the prosecution history, a person skilled in the art would reasonably understand the scope of the claim.

MR. VANDENBERG: Your Honor, we may or may not, depending on how the Solicitor General would apply that standard to a claim that has two reasonable interpretations after the person of skill in the art reads the claim in light of the specification and applies all the interpretive tools.

JUSTICE GINSBURG: The Court has to come up with a formula. You were saying the Federal Circuit’s formula is no good. The Solicitor General has, as the Chief Justice just said, has suggested an appropriate formula. And you say, well, it depends on the application. As a formula, do you agree?

MR. VANDENBERG: Your Honor, we we think it’s it would certainly be an improvement over the Federal Circuit’s amenable to construction and insolubly ambiguous test. The Solicitor General refers to reasonably understand. The parties have agreed on the phrasing of “reasonable certainty.” We think “reasonable certainty” comes out of this Court’s cases, and therefore, we prefer that. To the extent, obviously, “reasonably understand” means the same as “reasonable certainty,” then then we accept that.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Well, that’s what I’m having trouble dealing with. I suspect your friends on the other side will say yes, right, that they accept that, too. And you say, but it can’t be insolubly ambiguous or not amenable to construction. And they say, well, that’s not really what the Federal Circuit said.

So until we get to the application, I don’t see much disagreement among any of you about the standard or what’s wrong with the Federal Circuit’s articulation. And the questions kind of suggest we move very quickly into the particular invention and the application. And I’m just I’m curious what you want us to do if it seems like in every case, we have to get right into the application rather than the legal standards.

MR. VANDENBERG: Well, I think the the key dispute here is what happens if, after all the interpretive tools are applied, there’s a genuine ambiguity, meaning there really are two reasonable interpretations of the claim. Genuine ambiguity, person of skill in the art applying all the interpretive tools, trying to understand the claim. What happens then?

Our position is that if such a claim, which essentially points in two different directions, is indefinite, the problem with the Federal Circuit’s test is the Federal Circuit would not find that indefinite. Instead, the Federal Circuit would pick one because it’s amenable to construction. They would pick one. They would then ask is the construction they picked itself sufficiently clear for a person of skill in the art.

JUSTICE ALITO: What if a what if a person who’s a skilled artisan says that the claim could mean A and it could mean B, they’re both reasonable constructions, but this person is reasonably certain it means A, but not B? What would happen then?

MR. VANDENBERG: Well, I think the the proper analysis would be to look at the alternative construction and ask: Was that a reasonable interpretation? Was the second interpretation a reasonable interpretation of the claim? And courts every day make judgments like that, whether interpretations, for instance, of statutes. A second interpretation of a statute is reasonable.

JUSTICE SCALIA: Well, the only the only analog that comes to my mind immediately is our review of agency action. Is is that the standard that you want us to use? If if, you know, it’s within the scope of the ambiguity, oh, we don’t think that’s the right answer. But it’s close enough for government work. Is that is that what you want us to apply to patents?

MR. VANDENBERG: No, Your Honor, because the starting point here is the text of the statute. The text of the statute could hardly be more emphatic. Section 112 requires that the invention be described in full, clear, concise, and exact terms and then be claimed particularly and distinctly. Given that text of the statute, given the statutory purpose of protecting the next innovator from uncertainty, we think that that statutory language needs to be enforced, you know, forcefully.

JUSTICE SCALIA: Can it be reasonable but wrong.

MR. VANDENBERG: No, Your Honor. If a claim

JUSTICE SCALIA: I see. Whatever interpretation is wrong is ipso facto unreasonable?

MR. VANDENBERG: If if I understand correctly, a claim has only one proper construction. If a claim is subject

JUSTICE SCALIA: Okay. So whatever is wrong is is, by your definition you know, we we construe statutes all the time, and we certainly don’t think that the result we come to is the only reasonable result. We think it’s the best result, but not the only reasonable one. But you’re saying in this field there’s a right result and everything else is unreasonable.

MR. VANDENBERG: What what we’re we would analogize it most closely to to the Chevron ambiguity analysis.

JUSTICE SCALIA: Yes, that’s what I proposed first. But I thought I thought you didn’t like that.

MR. VANDENBERG: Well, if I misunderstood the question I apologize. But my understanding is in order to determine whether or not there is ambiguity in the statute, that the Court first looks to the statutory language and then applies interpretive tools. The same is true here. And then the Court if the Court finds there are more than one reasonable readings, then the Court will designate the the statute as ambiguous and then move on for the remainder of the Chevron analysis.

Under this statute, however, if the Court determines the claim is ambiguous, the proper result is invalidity.

JUSTICE GINSBURG: Well, what is what is the ambiguity? Is it I thought from your brief that it was the term “space relationship.” Is that the what what is the ambiguity?

MR. VANDENBERG: Yes, Your Honor. It is the term “space relationship” in the context of the claim. And again, the ambiguity is that this claim either covers all possible spacing of the electrodes within the boundaries that we’ve discussed or it only covers special spacings of the electrodes that are a result of trial and error in order to achieve the desired result. Those are hugely different claim scopes and that that uncertainty between those two is what would chill innovation.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Did you did you proffer any evidence below showing that a person with ordinary skill in the art did not understand what this claim meant? Your brief seems to rely only on the dispute between the majority and the concurrence. But was there did you proffer any evidence below?

MR. VANDENBERG: Your Honor, we did not proffer our own experts. The the evidence below included that Biosig’s own expert asserted that each of the competing constructions was reasonable, in essence. More specifically, he said that this was Dr. Gannoulas said at Joint Appendix 274 that “The person of skill in the art could readily discern the trial court’s construction of spaced relationship.” The trial court’s construction was any spacing.

Then the expert went on and said, “The person of skill in the art could easily discern the claim scope because the EMG signals have to be substantially removed.” That was the competing functional construction of spaced relationship. So their own expert supported both of these competing constructions and the reason they were comfortable doing that is because

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Now, I have a really big problem, which is we as Justices disagree on the meaning of things all the time, and one side will say, this is perfectly clear from the text of the statute, from its from its history, from its context. And we do all the statutory tools, and there will be one or more of us who will come out and say, no, we think it’s a different interpretation. Would we have any valid patents in the world if that’s the standard that we that we adopt? That if any judge on a panel thinks that there’s another interpretation, that that’s sufficient to invalidate a patent as indefinite?

MR. VANDENBERG: Your Honor, we are not taking the position that because the judges below disagreed on the construction, that that is dispositive or proves ambiguity in the claim. We we did say the fact that Biosig itself took both competing constructions as the need arose

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: But the majority but the majority here said that it was clear from the prosecution history, the specifications, and the description that this was definite. I don’t know on what basis I would have to overturn their review of that issue.

MR. VANDENBERG: Well, that that Biosig has taken both claim constructions. We’ve not seen them assert that either claim construction was unreasonable. The majority did not find the concurrence’s construction unreasonable. Nor did it find the trial court’s construction unreasonable. Their experts took both positions. So we have a claim that on its face I mean, the starting point is looking at the patent, of course, not what judges or experts or parties said later. The patent on its face is grammatically ambiguous. There is a whereby clause dangling in the middle of the claim that says whereby something good happens.

JUSTICE SCALIA: Yes. We understand all that. I I’m still having trouble understanding what your standard is. You you agree that your standard is not, there is a right answer and everything that is not the right answer is unreasonable. That’s not your position.

MR. VANDENBERG: That’s right, Your Honor.

JUSTICE SCALIA: Right?

MR. VANDENBERG: Right.

JUSTICE SCALIA: Okay. Then you invoke Chevron. Do you mean that anything that would pass Chevron’s step one is okay?

MR. VANDENBERG: Your Honor

JUSTICE SCALIA: That is, if it would pass Chevron’s step one it’s ambiguous.

MR. VANDENBERG: Well, if let me be clear about “pass.” If it’s ambiguous under Chevron step one, then that is a close parallel to being ambiguous under under Section 112, paragraph 2. But again, our starting point, of course, is not Chevron. It’s the statutory text, which and the standard we submit is to assert I’m sorry, to enforce the statutory text by its plain terms.

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Would this would this help? Do you agree that the standard at the PTO, and let’s say that it’s whether or not the claim is definite if a person skilled in the art would be reasonably certain of its scope. Is the standard used by the PTO the same standard that the CA Fed ought to use?

MR. VANDENBERG: Yes, it is, Your Honor.

JUSTICE KENNEDY: All right. How does that’s a sensible answer, I think. Now, how does the presumption of validity bear on on the application of the of that same standard in the court of appeals?

MR. VANDENBERG: The presumption of validity certain applies to this defense. It requires the challenger to raise the defense, to preserve the defense, plead it as affirmative defense, to make the initial argument as to why the claim is

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Doesn’t that imply some deference on findings of fact?

MR. VANDENBERG: Your Honor, it would be rare for there to be, in an indefiniteness case, to be any underlying finding of fact. The the issue of indefiniteness is really subsidiary.

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Does it imply what sort of deference does it accord to the PTO?

MR. VANDENBERG: If indeed

JUSTICE KENNEDY: That is, the presumption of validity, does that accord some deference to the PTO? And how would that apply or not apply here?

MR. VANDENBERG: It would apply it does not apply in this case. There are no fact findings out of the Patent Office regarding indefiniteness. But if there was the same indefiniteness issue came up and the Patent Office found, for instance, that a term of art, let’s say nanotechnology, biotechnology term of art had a particular meaning, then that factfinding may be entitled to deference by the trial court.

However, indefiniteness itself is a legal determination. The Federal Circuit said that. They review this. They know

JUSTICE KENNEDY: So there’s no deference to the PTO as to that legal interpretation.

MR. VANDENBERG: No, Your Honor, no more than there’d be deference to the Patent Office claim construction or any other legal decision.

JUSTICE KAGAN: The the quotation that the Chief Justice read to you from the Solicitor General’s brief referred to the use of prosecution history. Do you agree with the Solicitor General about that use, about the permissibility of that use?

MR. VANDENBERG: Yes, Your Honor, so long as the prosecution history that’s being used to clarify existed at the date the patent issued. The person of skill in the art again is supposed to be motivated to innovate around the patent the day it issues. Here there is a reexamination prosecution history. Sometimes there is later prosecution history in a related patent. That type of prosecution history shouldn’t be used to sort of ex post facto cure an initial indefiniteness.

But putting aside that rare instance, yes, the prosecution history and the specification are part of the interpretive tools that are available and would be used.

I think it’s important to remember here that there is no legitimate need or excuse for ambiguity in patent claims. Once the applicant has satisfied paragraph one and its strict requirements for describing the invention, it is easy to claim the invention particularly and distinctly. The only reason that there are so many ambiguous claims out there today is that patent attorneys are trained to deliberately include ambiguous claims. Ambiguous claims make the patent monopoly more valuable. Every patent attorney knows that.

JUSTICE GINSBURG: The government tells us there are some 22,000 patent grants since 1976 that use the term “spaced relationship.” I suppose many of those would fail your test?

MR. VANDENBERG: Not likely, Your Honor. It would be highly unlikely in more than 99 percent of those cases that there’d be any uncertainty of what “spaced relationship” meant. The problem here is not those words. It’s the grammatical ambiguity in the claim. It’s the fact that the specification did not describe, even arguably, the invention. That wasn’t described, the trial and error spacing, until 15 years later, and that the patent specification has no concrete examples of embodiments inside the claim or outside the claim.

So we ask that the Court reaffirm its precedents in United Carbon, General Electric and Eibel Process. Eibel Process upheld the claim that had vague sounding language. The language was “high elevation,” “substantial elevation,” but it was upheld because that patent specification concretely described the invention, its theory of operation, concrete examples that came inside the claim scope, concrete examples that fell outside. And that’s why that patent satisfied the particular and distinct claiming requirement and this one does not.

I’ll reserve the balance of my time.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Thank you, counsel.

Mr. Harris.

Oral Argument of Mark Harris for Respondent

MR. HARRIS: Mr. Chief Justice, and may it please the Court:

The decision of the Federal Circuit should be affirmed for two reasons: First, that court correctly held that the test for definiteness is whether a claim puts a skilled artisan on reasonable notice of the boundaries of the invention, and secondly, whatever

JUSTICE SCALIA: If that’s if that’s what it held we wouldn’t have taken this case. I thought we took it because it had some really extravagant language.

MR. HARRIS: The court, the court below used the word

JUSTICE SCALIA: I mean, it’s one thing to run away from that language, as your brief does. It’s another thing to deny that it exists.

MR. HARRIS: Justice Scalia, we are not denying that those words exist, “insolubly ambiguous,” but what I think this court below, the Federal Circuit, in this case explained, and it’s explained consistently, is that that those two words are not the test all by themselves. In this very case

JUSTICE KENNEDY: You would agree, I take it, that if, was it, “insolubly ambiguous” were the standard that the court used, that we should reverse?

MR. HARRIS: If there were no other context and only those words alone would be used, it seems that some district courts might misinterpret those words, as the Solicitor General has mentioned, but

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: So it was fair, as I suggested earlier, nobody agrees with that formulation; right?

MR. HARRIS: Yes, I guess so, Your Honor. But I want to just want to clarify what that point is. What the Federal Circuit said below, the full statement of its test that it was applying in this case, was: If reasonable efforts at claim construction result in a definition that does not provide sufficient particularity and clarity to inform skilled artisans of the bounds of the claim, the claim is insolubly ambiguous and invalid for indefiniteness. There is no suggestion that the court

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: There is a subtle no, there is, if you read that language carefully. It seems to be saying that what has to be reasonably definite is the court’s construction, and it takes the emphasis away from whether a skilled someone skilled in the art would be definite. There is a big difference between can I read this and give it a construction and whether or not a construction is definite enough so someone skilled in the art could understand it.

MR. HARRIS: We would completely agree that the test needs to include what the skilled artisan would have understood at the time.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: That’s my problem with the Federal Circuit’s articulation and as you read its decisions. Its focus is not always on that question. Its focus seems to be on the reasonableness of its construction, as opposed to the reasonableness of a skilled artisan’s or whether skilled, someone skilled in the art could reasonably construe the scope of this patent.

MR. HARRIS: But I think it’s quite clear from the way the Federal Circuit actually applied the standard in this case that the Federal Circuit was looking to what the evidence was as to what skilled artisans would do with this claim language. If anything it’s Nautilus that’s arguing that it doesn’t seem to matter what a skilled artisan thought at the time.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: So what do you see as the difference? He says that the concurrence’s definition is different from the majority’s. The government explain I read your brief. I know what you think the difference is, but

MR. HARRIS: Well, between the majority and the concurrence below, first, we don’t think

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: He says there is a difference in scope, so address that.

MR. HARRIS: Yes.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Why don’t you see that as being a difference of importance?

MR. HARRIS: It would be a difference if there were a difference in scope, but there isn’t one. I think it’s very important to look at what the majority and the concurrence actually did. The majority was addressing definiteness. The majority did that in two steps. The majority said we are going to apply the principles of claim construction. The first thing it did was it looked to the claim language, the written specification, the diagrams, all the traditional tools of patent interpretation. It said there is definiteness here because there are bounds to the spaced relationship. It isn’t just anything, it has to be greater than zero, it has to be less than the width of a hand. It’s implicit in the actually explicit in the statements of the patent.

Then it said that the functional limitation, which is the whereby clause in the patent, sheds additional light. That’s where the concurrence got off the train and the concurrence said: I don’t think we need to reach that issue. Nautilus has turned that approach on its head. Nautilus says that the fact that the concurrence didn’t think it was necessary to reach the functional limitation, in fact said that it’s not before us for procedural reasons, Nautilus reads that as if the concurrence was somehow disavowing or disclaiming the majority’s approach. It never said that. It was a procedural argument that it had. Then, in fact, there is no disagreement between the majority and the concurrence.

JUSTICE SCALIA: Would this patent be valid if the concurrence’s approach prevailed? It wouldn’t work, would it? It would not work. The mere fact that you spaced it somewhere where the hands can touch it would not necessarily produce the result, would it?

MR. HARRIS: If the patent said nothing other than there is a space between

JUSTICE SCALIA: That’s all the claim said.

MR. HARRIS: Well, no, no, Justice Scalia. The whereby clause explicitly said it described the structure. This case is quite different from General Electric, where there was no structure being given. It said that there is going there are going to be EMG signals that are going to be detected by the electrodes.

JUSTICE SCALIA: Right.

MR. HARRIS: Then those signals, which will be detected as equal, are going to be fed into a differential amplifier and thereby subtracted or canceled out.

JUSTICE SCALIA: Whereby. Whereby. I would read that as saying so long as you put the spacing at some point where the hands can touch it and they are not touching, that will produce the result that the signals will be equalized. That’s how I read the claim.

MR. HARRIS: Well, in fact, if the electrodes are configured in such a way that they detected the signals as equal

JUSTICE SCALIA: No, no.

MR. HARRIS: it would produce that.

JUSTICE SCALIA: No. Yes, I understand that, but that’s not what it says. It doesn’t say space the electrodes in such a manner that the signals coming from each side will be equal and you’ll have to do this by trial and error. That’s not what it says. It just says, you know, keep the electrodes apart. They have to be apart so that the hands don’t touch, and on the other hand they can’t be outside the scope of what the hands grip. That’s all it says. Whereby, if you do that, the signals will be equalized. That’s that’s how I would read it. It wouldn’t work that way, would it?

MR. HARRIS: It wouldn’t work if it gave no specifics. But this is where the fact that it all depends on what the skilled artisan would do is critical. Because there was uncontested evidence that a skilled artisan in 1992 was able to read this patent and understand how to put together this invention in such a way that it worked. In fact, Dr. Galiana’s research assistant did it, in 2 hours was able to build this invention based on the diagrams.

JUSTICE BREYER: I’m a little confused here. Imagine there are two kinds of electrodes, a blue one and a green one, and you have to have a blue one and green one on left hand and a blue one and green one on right hand. And now, you cannot let them touch. The blue can’t touch the green. I got that. And suppose on your left hand you put the blue one here and the green one there. And in the right hand, you put the blue in here and the green in here. See, they’re not touching, but they’re different distances from each other in the two hands. Does it work or not?

MR. HARRIS: If the distances on the two sides

JUSTICE BREYER: Look, look. This is like that one hand.

MR. HARRIS: Yes.

JUSTICE BREYER: And this one’s like the other hand. Okay? So does it work or not?

MR. HARRIS: I don’t I don’t know whether

JUSTICE SCALIA: Let the record show that the Justice is holding his fingers in the air.

(Laughter.)

JUSTICE BREYER: All right. Look, on the green one is two inches the space between the green one and the right one is like a half inch for the left hand, and it’s like one inch for the right hand. Okay? Does it work?

MR. HARRIS: If I could answer that question, Justice Breyer, in a in a more roundabout way. What the

JUSTICE BREYER: It was asked in a pretty roundabout way.

(Laughter.)

MR. HARRIS: What the uncontested evidence showed was that a skilled artisan at the time knew how to space electrodes.

JUSTICE BREYER: Then did he know that they had to be like if you put it two inches across here, so there are two inches between them, and over here it’s like a half inch between them, did he know it did work or did he know it didn’t work?

MR. HARRIS: He would know by

JUSTICE BREYER: He knew if it worked, but I want to know if it does work.

MR. HARRIS: It probably would not work in that situation.

JUSTICE BREYER: Okay. Now, as soon as you say that, that’s his point. His point is that when I read it I guess that’s the point that’s being made. When I read it, it just seems to me that the green one can’t touch the blue one, and the whole thing has to fit within your hand, so each of them catches a finger. And he’s saying that isn’t good enough. That doesn’t work. They have to be the same distance. And what that distance is, this document doesn’t tell us. And it doesn’t even tell us they have to be the same distance. So therefore, since it doesn’t tell us that, it’s ambiguous. Is that the correct argument? All right. We think it’s the correct argument. So now, what’s your answer?

MR. HARRIS: This Court has never found a problem with the need for some amount of experimentation in order to get the parameters exactly right.

JUSTICE BREYER: It doesn’t even say that. It doesn’t even say that. It doesn’t say go experiment whether somebody with great big fingers on one hand and tiny little fingers on the other hand

MR. HARRIS: In in Eibel Process, this Court faced as Mr. Vandenberg mentioned faced a case in which a method of manufacturing paper, all it said was that the angle of the supply of the pulp had to be high. Didn’t say anything more than that.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Is it part of an answer to Justice Breyer’s question that the diagram shows them equally spaced or is that not relevant?

MR. HARRIS: I don’t think the equal spacing is the only issue, Mr. Chief Justice. The issue is how do you find what that spacing is. And the answer, the uncontested answer, is that skilled artisans were able to do that very quickly. It’s not trial and error as if it’s throwing darts and just seeing what might work. It’s just like tuning a radio. Just happen to move things around in order you get that

JUSTICE KAGAN: Why doesn’t that

JUSTICE SCALIA: You know, I can understand that if the claim said that. If the claim said, you know, fiddle with it until it works. But it doesn’t say that. It just says, you know, spacing, and I would think so long as there’s space, they don’t touch, and they’re no more than the widths of the hands, it’ll work. It doesn’t say that. I don’t think the “whereby” is is an invitation to experiment.

But the other case you were talking about, tell us more about it. It just said a high angle.

MR. HARRIS: It’s at a high angle. Minerals Separation maybe is even a stronger case. In Minerals Separation, it was a method for extracting ore from metal metallic ore from

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Why are you why are you running from the working here is that it cancels out a signal, correct?

MR. HARRIS: Yes.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: And so what the majority said is that that function is part of the understanding of the spacing. Isn’t that what the majority said?

MR. HARRIS: It said that an additional constraint on the spacing is the fact that it has that it will work in a certain way.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: So I don’t know whether it has to be equal spacing or one could be one inch and the other half an inch apart. The bottom line is that to work, it has to cancel out, that that’s part of the scope.

MR. HARRIS: Yes. Yes.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Now, the concurrence said, no, you don’t have you can’t I’m not looking at the specification.

MR. HARRIS: Yes.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: I think it’s definite without it.

MR. HARRIS: Yes.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: All right. I don’t see how it could be. That’s what I think Justice Scalia is saying and Justice Breyer is saying, that if we don’t understand what the purpose is, how can that spacing be definite enough to make this thing work.

So tell us why you think that the concurrence’s interpretation is wrong. What’s he missing?

MR. HARRIS: The word when when it says “whereby,” the whereby means the elements that came before are going to produce that result.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Mmhmm.

MR. HARRIS: There’s never been a problem with the fact that a some amount of experimentation I hate to even call it that because it’s really just tuning dials on a radio may be needed in order to get the exact number, the exact setting.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Result that the specification

MR. HARRIS: But what the whereby clause says, it it conveys a structure. It says they have to be detected, the signals, in such a way that they’re equal. That normally wouldn’t be the case. In all the devices that existed up to that time, they wouldn’t be equal. Signals would come in from the right and the left hand that during exercise would be unequal, because when a person is running or moving, the right hand and left hand have different amounts of contact with the electrodes.

The whole novelty of this was the fact that you didn’t have to cancel EMG signals, what we call downstream, meaning by just filtering them out. They could be detected in such a way that they would be equal and then be cancelled.

JUSTICE KAGAN: Why didn’t the patent provide more specificity as to the exact spacing?

MR. HARRIS: Because like Eibel Process and like Mineral Separation, it wasn’t possible. It depended on too many variables. It depended the actual spacing in every single instance would depend on four variables. This was made clear in the expert declarations. The size of the electrode, the shape of the electrode, the spacing between the electrodes, and the materials, those four things. Just like in Eibel Process, what the Court said was, you may not know in advance what it is. But a skilled artisan will know.

JUSTICE GINSBURG: What about the apparatus on which the electrodes are mounted? Isn’t that another variable way you can’t say half an inch, because it depends, as you said, on size, shape, and materials of the electrodes. But doesn’t it also depend on the apparatus?

MR. HARRIS: Yes. Yes, it does. It does. The critical point is that there’s no question that a skilled artisan knew how to do this. They’ve introduced no evidence that a skilled artisan didn’t know this. In fact, their entire argument is based on attorneys coming up with arguments later.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: What what about the case that he postulated, an abstract one, where you have two perfectly reasonable constructions. What what happens then?

MR. HARRIS: If there are two constructions, each of which has survived the Markman claim construction process, and each one of them does the things that Markman says the correct construction needs to do, which is that it fully comports with the instrument as a whole and it preserves the patent’s internal coherence, then yes, we would agree in that case it’s indefinite. But what they’ve put forward

JUSTICE KAGAN: Doesn’t Markman exist for a different purpose? I thought that Markman existed in order to explain things to a lay juror or a lay judge. Why should the Markman test be used in this context, where we’re trying to figure out a different question entirely?

MR. HARRIS: Well, I I’m not sure I agree with the premise, Your Honor. The Markman explained that the nature of the test may need to be or the nature of the process may need to be necessarily sophisticated. It’s a hard thing to construe to construe claims, and we it depends critically on the abilities of the skilled artisan to do that.

Just to return to that to that to the point again, because I think it’s such an important point. All they’re relying on here are attorney arguments. In fact, this morning, just now, Mr. Vandenberg mentioned that the ambiguity isn’t even in the words “space relationship.” This is the first time I ever heard that. It’s actually somehow in the whereby clause. That argument was never made at any time below or up until now.

And the reason that’s critical I’m not arguing waiver but the reason that’s critical is the rule that Nautilus is suggesting here will encourage attorneys years after infringement has occurred to just come up with some way to argue that there is something that’s unclear in the patent.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Could I could I just go back to my you know, the two reasonable. Is there a range? The Chevron the Chevron analogy again comes to mind. Let’s say one is more reasonable than the other, but they’re both reasonable. What type of range do you have before you say that the patent is invalid?

MR. HARRIS: I think I agree with the comments that were the questions that were asked before, that it’s very common in matters of statutory interpretation to have different answers, some of which are reasonable but are incorrect. We hold we believe that the test requires that the if there’s there has to be more than one correct construction before it’s going to be indefinite. If it only depends on the fact that there are reasonable interpretations that are made in good faith that lawyers are arguing or that jurists have come to, that’s not going to be enough. Any more than it is

JUSTICE SCALIA: There’s never more than one correct construction. Even even when there is there isn’t. I mean, we always have to come up with an answer. And the patent office has to come up with an answer. It means this or it doesn’t mean this. Have you ever heard of a court that says, well, you know, it could mean either one of these?

MR. HARRIS: No. In fact, I think Justice

JUSTICE SCALIA: It’s a tie.

(Laughter.)

MR. HARRIS: I I think that’s the point. The point is that one of the constructions is going to be better. All they have suggested here is that both constructions, somebody in good faith made.

JUSTICE SCALIA: So then you win all the time.

MR. HARRIS: No.

JUSTICE SCALIA: There is no such thing as ambiguity, because there is always a right answer.

MR. HARRIS: As this Court has said in the rule of lenity context, there can be situations where a statute isn’t clear.

JUSTICE ALITO: It sounds like you really are advocating the “insolubly ambiguous” standard, that’s what you’re saying. Unless you have to throw up your hands at the end and you say, we can’t figure out which one this means, there is no correct interpretation, unless that’s the case, then the patent is valid.

MR. HARRIS: The premise of Markman is that in most, if not all, cases or many, many, many cases where there is going to be real substantial disagreement between two parties, good faith disagreement where each side is supported by its reading of the materials, nevertheless, the court can come to an answer and should come to an answer.

I just want to mention quickly, this Court has had several cases where words appeared to be ambiguous on its face and yet the Court didn’t have the trouble of applying them and interpreting them in the patent context.

Markman was a case about the word “inventory.” “Inventory” on its surface could mean either accounts receivable or the actual stuff. In the Yeomans case, the word was “manufacture.” Does “manufacture” mean the result or does it mean the process?

JUSTICE ALITO: Well, was the Federal Circuit wrong when it said the test should be insolubly ambiguous? Was that wrong or not?

MR. HARRIS: If “insolubly” means applying the standard tools of claim construction, then it’s correct to say that that is what’s required. But that term, I think by some district courts, I’ll acknowledge, may be misinterpreted to mean as long as we can come up with anything, and it makes it sound as if it’s not necessary to actually tie it back to the language of the patent.

If the court is doing it the correct way that Markman prescribes, looking at all the patent materials and the prosecution history, if it can come to an answer, then we would agree that answer that the patent is definite.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Do you agree with your adversary that the prosecution history is that at the time the patent was issued and not on reexamination or anything else subsequent?

MR. HARRIS: I think in this case it comes out the same.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: No, no. I didn’t ask that question.

MR. HARRIS: No, I think that the prosecution history later also can count.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Explain that. Because he says, and it seems logical, that you’re going to stifle inventiveness if people can’t, once the patent is issued, know how to get around it.

MR. HARRIS: Well, let me clarify what I mean by that. If evidence is introduced at a later stage during in, say, in reexamination, some of that evidence may be, it may be a court may be able to consider that at a later time as being relevant.

If I can finish the question.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: You mean the answer?

MR. HARRIS: Yes, the answer.

If the court in other words, if evidence, as here, was introduced at reexamination about what skilled artisans knew at the time, the mere fact that it was introduced at a later stage is not a problem.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Thank you, counsel.

MR. HARRIS: Thank you.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Mr. Gannon.

Oral Argument of Curtis Gannon for United States, As Amicus, Supporting Respondents

MR. GANNON: Mr. Chief Justice and may it please the Court:

I’ll start with a question that the Chief Justice asked. You already recited the standard that we support here, which is that a patent claims is sufficiently definite under paragraph 2, a person of ordinary skill in the art would reasonably understand the scope of the claim. And I understand Petitioner’s submission to be a dispute about what happens if there are two potentially reasonable constructions at the end of the Markman claim process.

And we think that if there are two constructions that are of nearly equal persuasiveness, then that would be ambiguous. But if one construction is appreciably better, then that is good enough without having to take the second step of saying that the second best construction that’s not as good and appreciably not as good IS is also unreasonable. We think that that’s not the way this Court or judges

JUSTICE BREYER: What worries me about that, which is certainly attractive, what you just say, is that lawyers will come up with all kinds of experts, you know. And quite often, if this situation ever arises, and I don’t know if it really ever does, it could reflect a difference of opinion among scientists. I mean, you could have those who followed the phlogiston logistic theory of fire. You could have those who follow the oxygen theory of fire. All we have to do is update that, and you could find different experts who would have different opinions while all agreeing that it is absolutely clear.

I doubt that the Patent Office will very often find that problem arising. And if it does, why not just say, forget about it? As long as you can say reasonable experts can clearly you know, what you just said that’s the end of it. And we’ll tell you what to do later, when we really find the problem or you tell us what to do. I mean, I’m having a problem about it, and I’m explaining what my problem was.

MR. GANNON: Well, I think that the question is what does it mean when the Court has demanded reasonable clarity or reasonable certainty, and that’s the standard that we read in this Court’s cases on definiteness.

JUSTICE BREYER: Can’t we just stop there? I mean, do we really have to go into this theoretical dispute between the two scientists, who have opposite theories of

MR. GANNON: Well, I don’t think it’s a dispute between two scientists with opposite theories. The question of what a person of ordinary skill in the art would think, I think that a person of ordinary skill in the art is a hypothetical legal construct, like the reasonable person from tort law.

JUSTICE SCALIA: When do we ever decide a case in which we would not say that our result is appreciably better than the result we reject?

MR. GANNON: Well, I think that there are times when the Court would recognize that it’s an authentically closer question.

JUSTICE SCALIA: Well, it’s still close, but not appreciably better. If it’s not appreciably better, we would have to say it’s a draw.

MR. GANNON: I don’t think that the Court has a unified field theory of

JUSTICE SCALIA: Well, I think the test you’re giving us is not much of a test, it really isn’t. It seems to me it says so long as there is a right answer, everything else is wrong.

MR. GANNON: No, I think it says that as long as the right answer is appreciably better than the second best answer, that you do not have to take the second step of having to declare

JUSTICE SCALIA: How big is appreciable?

MR. GANNON: I don’t

JUSTICE SCALIA: You don’t know.

MR. GANNON: I think it’s difficult to put a mathematical precise a mathematically precise number on it.

JUSTICE ALITO: That’s the whole problem with what you’re with what you’re saying. I have no idea what “appreciable” means. Let’s say we have a

MR. GANNON: Something more like 60/40 than 52/48. And I think in general the Court recognizes the difficulty of that type of mathematical precision in applying tests like what it means to be clear and convincing.

JUSTICE ALITO: Usually when we ask whether something is reasonable, we have in mind this reasonable person and the set of circumstances in which the reasonable person is going to act. So in torts, the reasonable person is going to engage in an activity that has some benefits but also has some risks; what would that person do in that situation.

Now, here you’re saying what would the reasonable skilled artisan do in what situation? What is this person doing, setting out to build the device? What

MR. GANNON: They are trying to understand the scope of the claim. And so, and I I do think it’s important here to recognize that there are two different questions that are getting conflated in some of the discussion. I think that with respect to definiteness under paragraph 2, as the court of appeals majority recognized, that this is in this case the question is whether the claim clearly states that it requires the electrodes to be arranged in such a fashion that they will have the effect of detecting substantially equal EMG signals at the electrodes. It’s not with downstream circuitry, which is what Petitioner suggested in the opening brief. In Petitioner’s reply brief they’ve suggested they could use some sort of protective sleeve on the electrodes, but that wouldn’t be consistent with the parts of the limitations that say that there needs to be physical and electrical contact with the electrodes.

And the majority recognize that there are multiple variables that come into play here, the spacing, the materials, the separation, as my, my cocounsel was just explaining, and but the disagreement between the majority and the concurring opinion here is just in whether the functional limitation inheres in the phrase “spaced relationship” taken in isolation or whether it can be read from the rest of the claim as a whole.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: When you say something like “appreciably better,” that’s a term that may acquire meaning over time. Just like reasonableness, we get a good sense of what it means. Is it your sense that the Federal Circuit has been applying its test in this case? I mean, not in this case but in a series of cases that is it is close to appreciably better or is it something quite different?

MR. GANNON: Well, we do acknowledge that the phrases that the Federal Circuit has used about “insolubly ambiguous” and “amenable to construction” are subject to be to be overread and

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Yeah, nobody likes

JUSTICE SCALIA: subject to being read, not overread.

MR. GANNON: Well, I think that they that they could cause mischief if applied in isolation. And we haven’t taken a position on every case that the court of appeals has applied these standards in, and I don’t think that the court of appeals was intending a marked departure from this Court’s overarching

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Are there cases where there are two reasonable constructions, but both would be patentable?

MR. GANNON: Well, I think

JUSTICE KENNEDY: Would that satisfy the specificity requirement of the statute?

MR. GANNON: I think that we are arguing now about when the second best construction ceases to be a reasonable one, I think. And I think that if the Court wants to think of just whether there is a good enough construction such that there is reasonable clarity as required under United Carbon and in the Minerals Separation case where the Court said that the certainty that’s required is not greater than is reasonable.

JUSTICE KAGAN: What do you think of this Chevron analogy, Mr. Gannon? Because sometimes we do say something close to it’s a tie. We say there are a couple of reasonable constructions or a number of reasonable constructions. We could pick one, we think it might be better, but it’s all close enough that we don’t think we ought to pick one. So similarly, it’s all close enough that the definiteness requirement has not been met. Is that a good analogy?

MR. GANNON: I I think that that would probably we think that the sorts of constructions that would be reasonable under Chevron that the agency could take as a second best construction probably aren’t sufficient to be the definite construction here. And so I I don’t think it’s a close analogy because we don’t think that anyone is seeking that type of deference to another decisionmaker as

JUSTICE KAGAN: No. I’m not sure I quite got that. It’s just that anything that would flunk Chevron step one and would go on to Chevron step two, you would say that that kind of ambiguity, the kind of ambiguity

MR. GANNON: No. I

JUSTICE KAGAN: that would get you to Chevron step two

MR. GANNON: I don’t think so.

JUSTICE KAGAN: is also the kind of ambiguity that would fail to satisfy the definiteness

MR. GANNON: No. And I’m sorry if I wasn’t clear about this before. I was trying to say that in a 60/40 situation that I said would be adequate here, such that the second construction did not prevent there from being sufficient clarity, I think that we would think that an agency would be entitled to choose the 40 percent option. But we don’t think that that would be that that would prevent the 60 percent option from being good enough in the context required here.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: The Federal Circuit seems to say that if there’s two reasonable constructions and one would make the patent valid, I think this goes to Justice Kennedy’s question, that they’re obligated to pick the one that makes the patent valid.

MR. GANNON: The case, I think I believe the case that’s being talked about there is cited in the Exxon opinion.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Uhhuh.

MR. GANNON: And that talks about when there are two equallyplausible constructions. I think that that probably is the the knife edge of insolubly ambiguous. And there, the Federal Circuit suggested that that, as Justice Scalia was was saying before, that that because there would be a decision rule, that you would pick the construction that would save the patent, that that would be okay.

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: Is that right?

MR. GANNON: I don’t think that that allows for sufficient clarity. We believe that if there are two constructions

JUSTICE SOTOMAYOR: So they’re wrong in that as well.

MR. GANNON: In that particular statement of of the rule, yes. We do think, however, that there is a distinction between the that the presumption of patent validity does play a role here. It doesn’t change the standard, but it it does it does play a role in indicating that, as the PTO has recognized, that courts will do more to save a patent than the PTO does when it’s examining one. And I would I would say that we also disagree with the notion

JUSTICE KENNEDY: How can that be if it’s the same test?

MR. GANNON: Well, it’s the overarching question is, is the same of whether a person skilled in the art would reasonably understand the scope of the claim, but

JUSTICE KENNEDY: And that’s the same test at both levels.

MR. GANNON: It’s it’s not the same test that the PTO applies in examination proceedings because it uses a slightly different threshold of ambiguity.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Are you finished with your answer?

MR. GANNON: I could give an explanation of why.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Could you do it in a sentence?

MR. GANNON: I could say that it involves the different circumstances there that include the different record, the different burden of proof, the lack of adversarial presentation there, and mostly critically, the fact that it’s easier to amend the claims before the patent has been issued.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Thank you, counsel.

Four minutes, Mr. Vandenberg.

Rebuttal Argument by John Vandenberg for Petitioner

MR. VANDENBERG: Thank you. I think the the essential points here are, first, the emphatic language that Congress chose, and then thinking about ambiguous claims. There is no legitimate need for ambiguous claims. There is a strong economic incentive for patent attorneys to draft ambiguous claims, not to put all their eggs in that basket. They want some clear claims in case some copyist comes along, but they want ambiguous claims so they can their client can treat it as a nose of wax later, as happened here. That is well established in the patent bar, that there is this strong economic incentive. But patent attorneys have ample tools to avoid ambiguous claims if this Court tells them that it will no longer be permitted. That that is the key here, is that there’s a strong economic incentive. The patent attorney and the inventor are in the best position to avoid the ambiguity that Congress prohibits and therefore, the problem is, the Federal Circuit has blessed ambiguity with its test. And in order to stop all of the problems that the amici have pointed out that are caused by ambiguous claims, we submit this Court needs to be clear and go back to United Carbon and General Electric and to the statutory text and be clear that ambiguity is simply not permitted.

In terms of how the Federal Circuit ruled here, and we point to the majority’s opinion at petition appendix 15(a), the court, the majority, definitely applied the insolubly ambiguous test. They said, “Because the term was amenable to construction, indefiniteness here would require a showing that a person of ordinary skill would find spaced relationship to be insolubly ambiguous.” And therefore, if the Court rejects that test, we submit, at the very least, the Court cannot affirm the judgment below on that basis.

But more importantly

JUSTICE GINSBURG: But the Federal Circuit said something I’m looking at the petition appendix at 20(a) that sounded very close to what the government standard is. It said, “Sufficiently” “that the claim provides parameters sufficient for a skilled artisan to understand the bounds of spaced relationship.” That sounds very close to what the government says and it isn’t they don’t say anything about insoluble in in that statement.

MR. VANDENBERG: It is true that here in some of their cases, the court will the Federal Circuit will use language like that saying that one could have understood. However, it’s clear they were not applying the type of test that United Carbon and General Electric required. They did not even consider whether the person of skill in the art may have read the claim the different way.

And in terms of the two different claim scopes, we would simply invite the Court’s attention back to our reply brief at page 20, which explained the different claim scopes. We think the government misunderstood the point, and therefore, in the reply, we amplified it some more.

But as as I said, the Court at the very least should not affirm. But we think it’s important here for the Court to create another concrete guide post. In KSR and Bilski, this Court provided a huge service to the patent bar in applying the correct law to an actual patent claim, creating concrete guide posts for Section 101 and 103. Well, the patent bar and the trial courts need another concrete guide post if applying the correct law of Section 112, paragraph 2 to this particular claim.

If there are no further questions, thank you.

CHIEF JUSTICE ROBERTS: Thank you, counsel.

The case is submitted.

(Whereupon at 11:07 a.m., the case in the above entitled matter was submitted.)