Contents:

Patents are complex documents that bury a handful of important sentences under a mountain of fluff and jargon. If you’re going to read a patent (and I urge you not to) you might as well start with the important parts, and read them correctly.

Let’s suppose you want to figure out whether your new technology might infringe some patent. Here’s a simple strategy I might use to start the infringement analysis.

First, skip down to the “claims.”

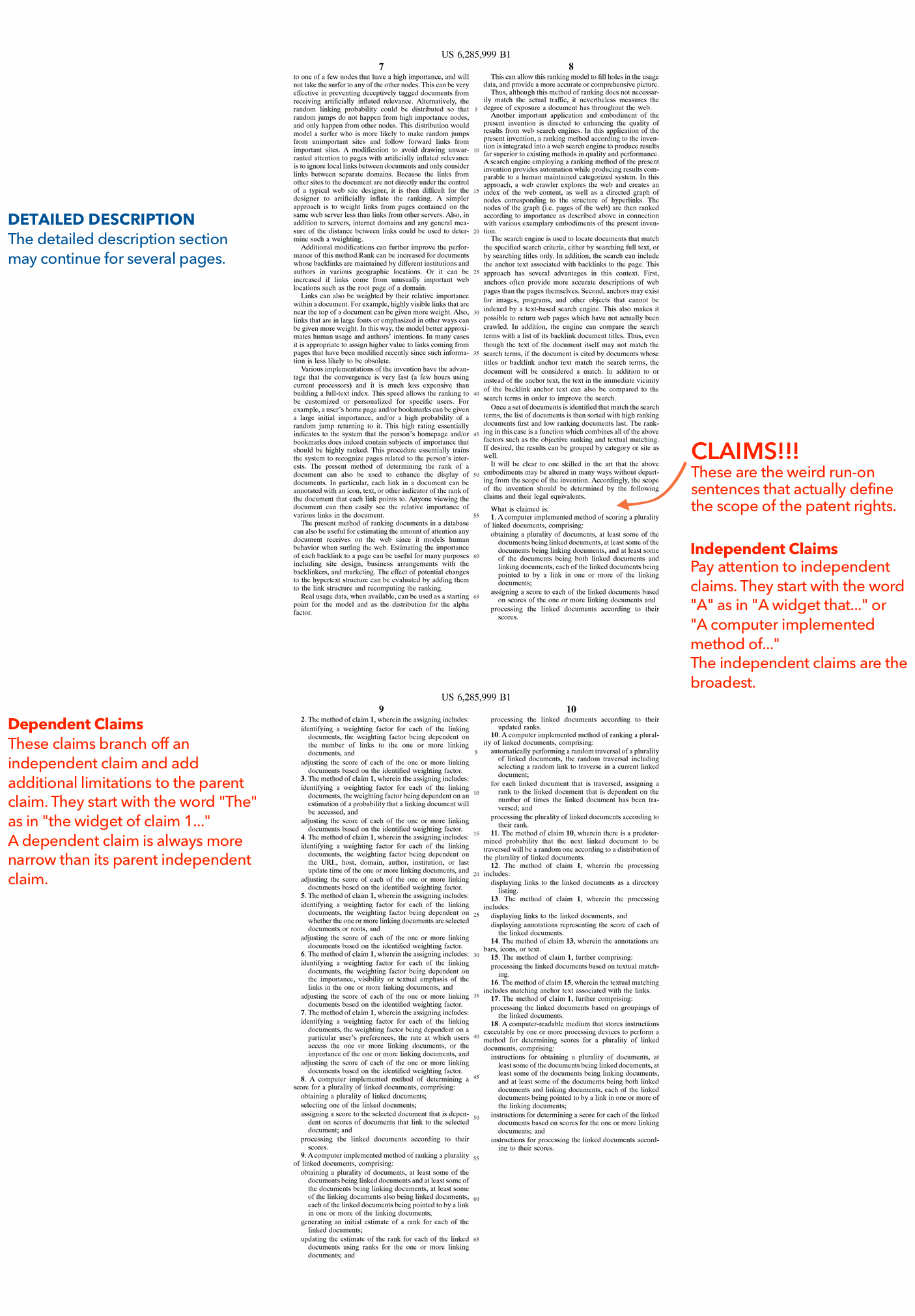

The claims (MPEP 608) are a numbered list of run-on sentences buried toward the end of the patent. Although they come last, the claims are actually the meat of the patent - they define the actual patent rights. The other sections are auxiliary - they are supposed to help explain the claims.

Next, highlight all the “independent claims.” These are the claims starting with the word “A”. For example, “1. A swizzle stick adapted to…” or “9. A computer implemented method for…” There are probably 2 or 3 of these independent claims, but there can be more.

The others claims are the “dependent claims.” The dependent claims start with a phrase like “The ___ of claim ___” and refer back to a previous claim. For example, “7. The swizzle stick of claim 1, further comprising…” Ignore the dependent claims for now. Google Patents actually displays dependent claims in gray text, making it easy to skim past them (UX!!).

In 2 minutes, we’ve narrowed a huge patent document down to a small handful of important sentences - the independent claims. Next we will break down the independent claims and compare them to our technology.

Any Infringement?

We want to determine whether our technology would infringe this patent we’re reading. It will infringe if it incorporates every element of any one of the claims. Fortunately, we only need to check the independent claims at this point.1

Claims read like run-on sentences, but if you’re lucky the run-ons will be broken down into sections and even subsections. Take a look at the first claim in our annotated patent2. The first claim is a method with 3 steps, and the first step has 4 qualifications:

- A computer implemented method of scoring a plurality of linked documents, comprising:

- obtaining a plurality of documents,

-

- at least some of the documents being linked documents,

-

- at least some of the documents being linking documents, and

-

- at least some of the documents being both linked documents and linking documents,

-

- each of the linked documents being pointed to by a link in one or more of the linking documents;

- assigning a score to each of the linked documents based on scores of the one or more linking documents and

- processing the linked documents according to their scores.

If your technology does not incorporate even one of these steps or qualifications, it’s (probably) not infringing this claim. Lets say your technology does 90% of the things described in claim 1, except that none of the documents are both “linked documents and linking documents” (as required by the claim). Then your technology is (probably) not infringing on this claim 1. It’s an all-or-nothing analysis, at least at this preliminary stage. If even one element of the patent claim is missing from your technology, your tech is (probably) not infringing on the patent.

Parts of the claim might be ambiguous on their own. So at this point, we start referring back to the rest of the patent document to try to understand whether words in the claim have some special meaning. This type of claim interpretation (MPEP 2111) analysis is complicated, and beyond the scope of this post. In theory, if you are a reasonably competent engineer/scientist in the field of this patent, the claims should be written in language you can understand. (This is rarely true, but in theory, it’s required (MPEP 2163).

Annotated Patent

When reading a patent, first skip to the independent claims, and read them carefully. The rest of the document is far less important. Here’s an annotated patent explaining some of the other parts of the patent document.

The Rest of the Patent

It’s easy to forget that the claims, and only the claims, define patent rights. The rest of the patent document is auxiliary to the claims. So remember:

- The title does not define the patent rights. If the title is “toaster”, the patent probably covers some minor aspect of a toaster. It does not cover every aspect of every toaster, and certainly not the very concept of a toaster. It’s usually best to ignore the title.

- The drawings do not define the patent rights. The claims probably highlight some small aspect of the drawings, and this small aspect is part of the patent rights. The rest of the drawings may help explain the claims, but that is all they do.

- The summary is just a summary of some technology. The claims probably highlight some small part of the summary, and this small part is part of the patent rights. The rest is fluff.

Prior Art

A prior art analysis (MPEP 706) is similar to an infringement analysis. I’ll explain a quick taste of the prior art analysis because it’s useful to compare it to the infringement analysis. First, check the prior art reference’s date. Is it older3 than the patent? If so, it might be prior art. If the reference is newer than the patent, it’s not prior art.

Next, skip down to the claims. As with the infringement analysis, the claims are the most important part of the patent for a prior art analysis. But unlike infringement, we will need to review all the claims, not just the independent claims.

Check to see whether the prior art reference explains every element of a claim in the patent. If so, the reference “anticipates” the claim, and the claim is invalid. Repeat this process for each claim. Even if an independent claim is anticipated and invalid, the dependent claims that branch off of it might still be valid.

The prior art reference might be another patent, or it might be a journal article, white paper or most any other published document. If the prior art reference happens to be another patent, the claims in this prior art patent are not particularly important. Any part of a prior art patent (lets call it “old-patent”) can help invalidate a later patent (“new-patent”). The claims are the critical part of new-patent, but not of old-patent.

Even if a patent claim is not anticipated, it might still be invalid as obvious. The obviousness analysis (MPEP 2141) basically asks whether someone might reasonably combine two or more references to teach every element of a patent claim. It’s complicated, so we will save the details for another post.

Conclusion

I hope this helps provide a general overview of how to read a patent. Patent law is complicated, and full of traps for the unwary. This quick guide provides you with just enough information to be dangerous. If you have an important patent question, hire a patent lawyer.

Please feel free to ask general questions in the comments. I’ll try to answer, and questions will help me improve this guide. I can’t answer specific questions about your patents and technology.

Eric is a patent and technology lawyer in Seattle. He’s helped defeat patent trolls, and is learning to make Arduino toys.

-

We don’t need to review the dependent claims at this point because dependent claims always add additional elements to a claim - they are always narrower in scope than the parent independent claim. If a technology does not infringe an independent claim, it cannot infringe any dependent claims branching off of the independent claim. Lets say independent claim 1 requires elements A and B, and dependent claim 2 requires elements A, B and C. If your technology doesn’t use element B, then it’s not infringing independent claim 1. And since dependent claim 2 is narrower than claim 1 (it requires element B as well as new element C), your technology is necessarily not infringing claim 1. (Dependent claims become more important when someone tries to invalidate the parent independent claim - invalidating the parent doesn’t necessarily invalidate the narrower child claim). ↩

-

which happens to be the patent for Larry Page’s PageRank algo ↩

-

There are lots of complicated rules (MPEP 2152) for determining whether a possible prior art reference is newer or older than the patent. ↩