Design patents protect the appearance of a design for 15 years. They are relatively inexpensive and a surprisingly effective legal tool, for both digital user interface design (the bits) and industrial design (the atoms).

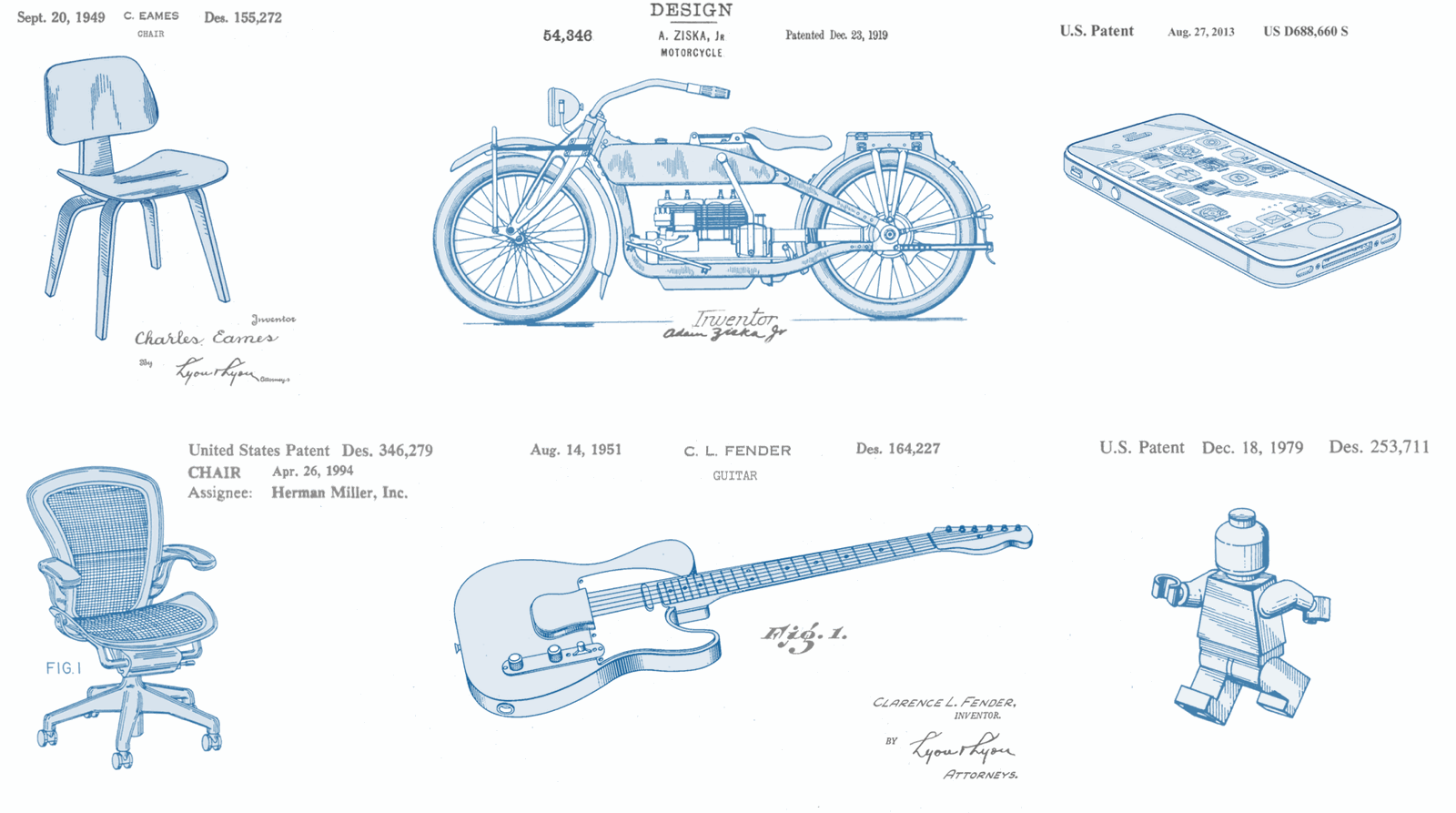

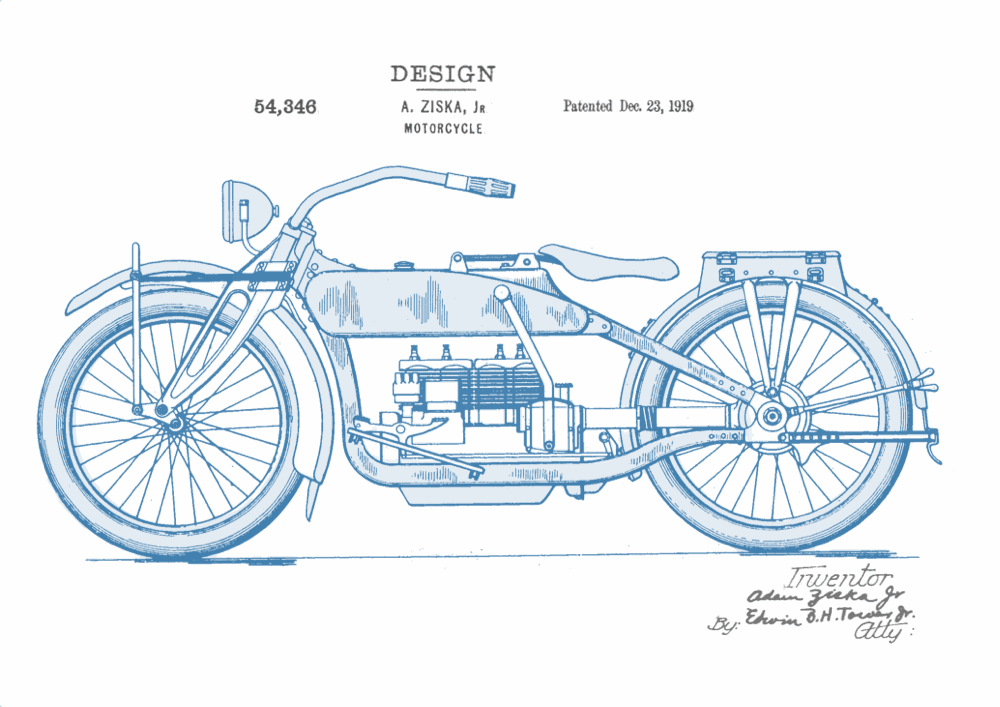

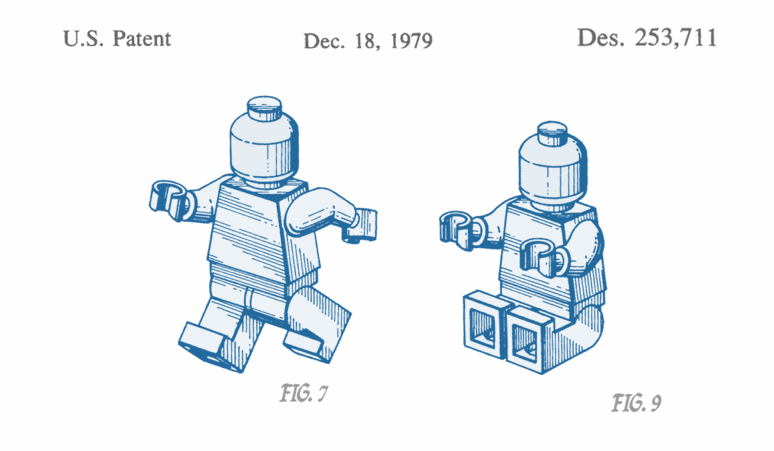

Designers have used these patents to protect renowned works like Clarence Fender’s electric guitar, Adam Ziska’s early Harley Davidson motorcycle, Charles Eames’ iconic chairs, and even Christiansen’s little lego man. Design patents also protect moderns works of high-tech and digital design like Google’s famously simple search interface, and of course, every iteration of Steve Jobs and Jony Ives’ iPhone.

Contents:

Law of Design Patents

Application Process. The design patent application is relatively simple. The drawings are the most important part, particularly the difference between solid lines and dashed lines. The application process takes about a year from application to issuance. Budget about $2-3,000 in total costs for most design patents, and perhaps a little more for digital and UI design patent. This is much cheaper than a utility patent, which runs between $8-20,000.

Non-Functional. Where utility patents protection functional inventions, design patents protect “non-functional” inventions. Non-functional is defined loosely. The design patent statute limits protection to the “ornamental” design of a product:

Whoever invents any new, original and ornamental design for an article of manufacture may obtain a patent therefor… 35 USC § 171.

But courts interpret “ornamental” to really mean “non-functional.” Other courts have further interpreted “non-functional designs” to mean something like any design that is not entirely dictated by function. In practice, most industrial designs are eligible for design patent protection, even if the designs are partly functional.

-

The patent statute says design patents are available to protect the “ornamental design for an article of manufacture.”

-

which really means design patents protect “non-functional designs”

- which really means that design patents protect anything except designs solely “dictated by function.”

-

A design’s functionality will only make it non-patentable if its overall appearance is “dictated by function.” That is, if the design is governed solely by the product’s function, the design cannot be patented. On the other hand, if alternative designs are available for performing the same function, the design is not dictated solely by its function, and it can be patented. PHG Technologies v. St. John Companies, Inc., 469 F.3d 1361 (Fed Cir 2006).

Easy Litigation. Design patents are easy to enforce. The legal issues simply involve comparing the plaintiff’s design patent drawings to the defendant’s product. It doesn’t take an expensive team of experts to detect infringement or bring a case to trial. (Although expensive experts are often used in high-stakes design patent litigation, they are not necessarily required.) A judge or jury can simply compare the pictures in the plaintiff’s design patent to the defendant’s product.

Infringement. A design patent is infringed if “an ordinary observer, familiar with the prior art designs, would be deceived into believing that the accused product is the same as the patented design.” Richardson v. Stanley Works, 597 F.3d 1288 (Fed Cir 2010).

Prior Art. Prior art is relevant to this “ordinary observer” infringement comparison. The differences between the claimed design and the allegedly infringing design “are viewed in light of the prior art.” Since the ordinary observer is viewing the designs in light of the prior art, her attention will be “drawn to those aspects of the claimed design that differ from the prior art.” Crocs v. Int’l Trade Commission, 598 F.3d 1294 (Fed Cir 2010).

The closer the plaintiff’s design patent is to any prior art designs, the harder it is to show the defendant’s product is infringing. Where the prior art is similar to the design patent, even small differences between the design patent and the defendant’s design become important. “The ordinary observer, however, will likely attach importance to those differences depending on the overall effect of those differences on the design.” Crocs v. Int’l Trade Commission.

In litigation, defendants frequently use prior art to chip away at the plaintiff’s design patents. For example, when Apple alleged that Samsung’s “Galaxy Tab” infringed an iPad design patent, Samsung replied by digging up examples of prior art tablets:

Samsung was making a simple argument: the Galaxy tab doesn’t copy Apple’s ‘889 design patent, its just using public-domain design elements from the prior art like the rectangle with rounded corners found in the 1994 “Fiddler” tablet. (It was a well-reasoned argument, but did not persuade the jury, who returned a verdict in Apple’s favor to the tune of a billion dollars).

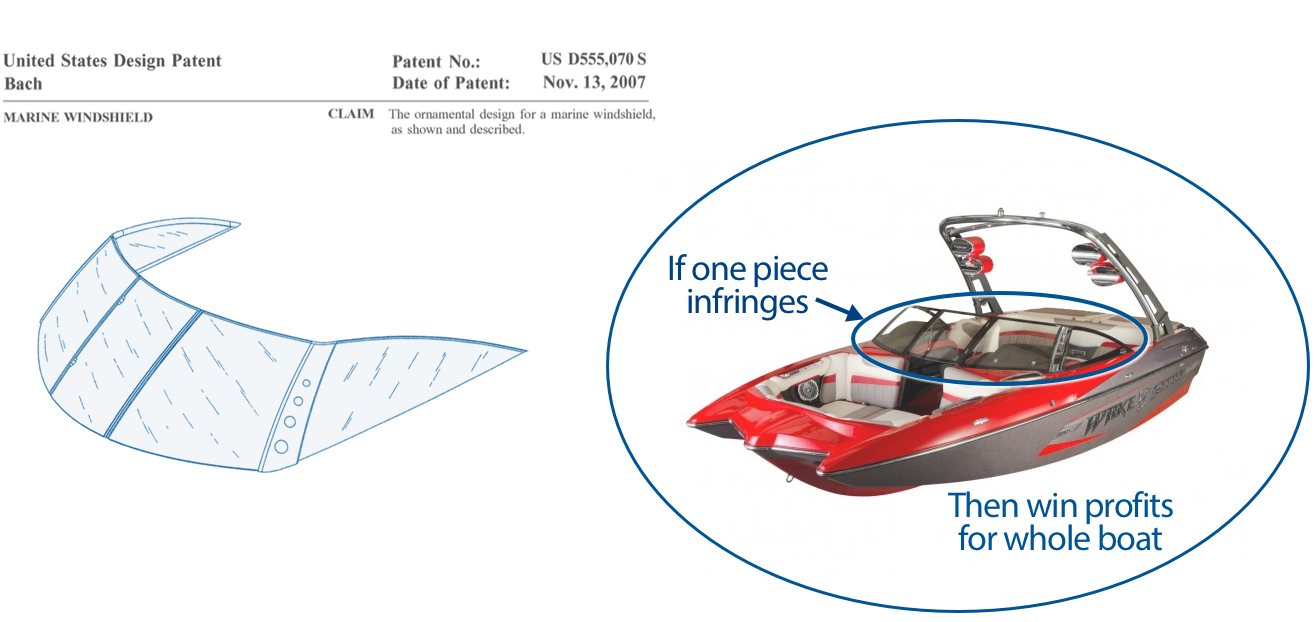

Penalty for Infringement. The penalties for design patent infringement are large, and often larger than in a comparable utility patent case. This is because design patent damages are not “apportioned.” In utility patent cases, damages are awarded in proportion to the extent that the infringing feature drove the defendant’s profits. But for design patent infringement, there is no such reduction. Instead, the plaintiff is awarded the infringer’s “total profit.”

For example, if a company sells a boat, and just the windshield of the boat infringes a “marine windshield” design patent, the patent owner is entitled to recover the “total profit” from the sale of the infringing boat.

Congress removed the apportionment requirement in 1887… Design patent owners are no longer required “to apportion the infringer’s profits between the patented design and the article bearing the design.” The intent of Congress to allow more expansive recovery for design patent owners is exhibited in the plain language of the statute, which allows recovery of “total profit” from anyone who sells “any article of manufacture to which such design or colorable imitation has been applied.” 35 U.S.C. § 289. In this case, Malibu sells boats, to which patented windshields have been applied. The plain language and intent of the statute support a conclusion that Pacific is entitled to Malibu’s profits from the sale of its boats with the windshield. Pacific Coast Marine Windshields, Ltd. v. Malibu Boats, LLC, (MD Fl Aug 22, 2014) (citations omitted).

The design patent owner may also be awarded an “injunction” – a court order forbidding the defendant from selling any products that use the plaintiff’s patented design.

Design Patent Drawings

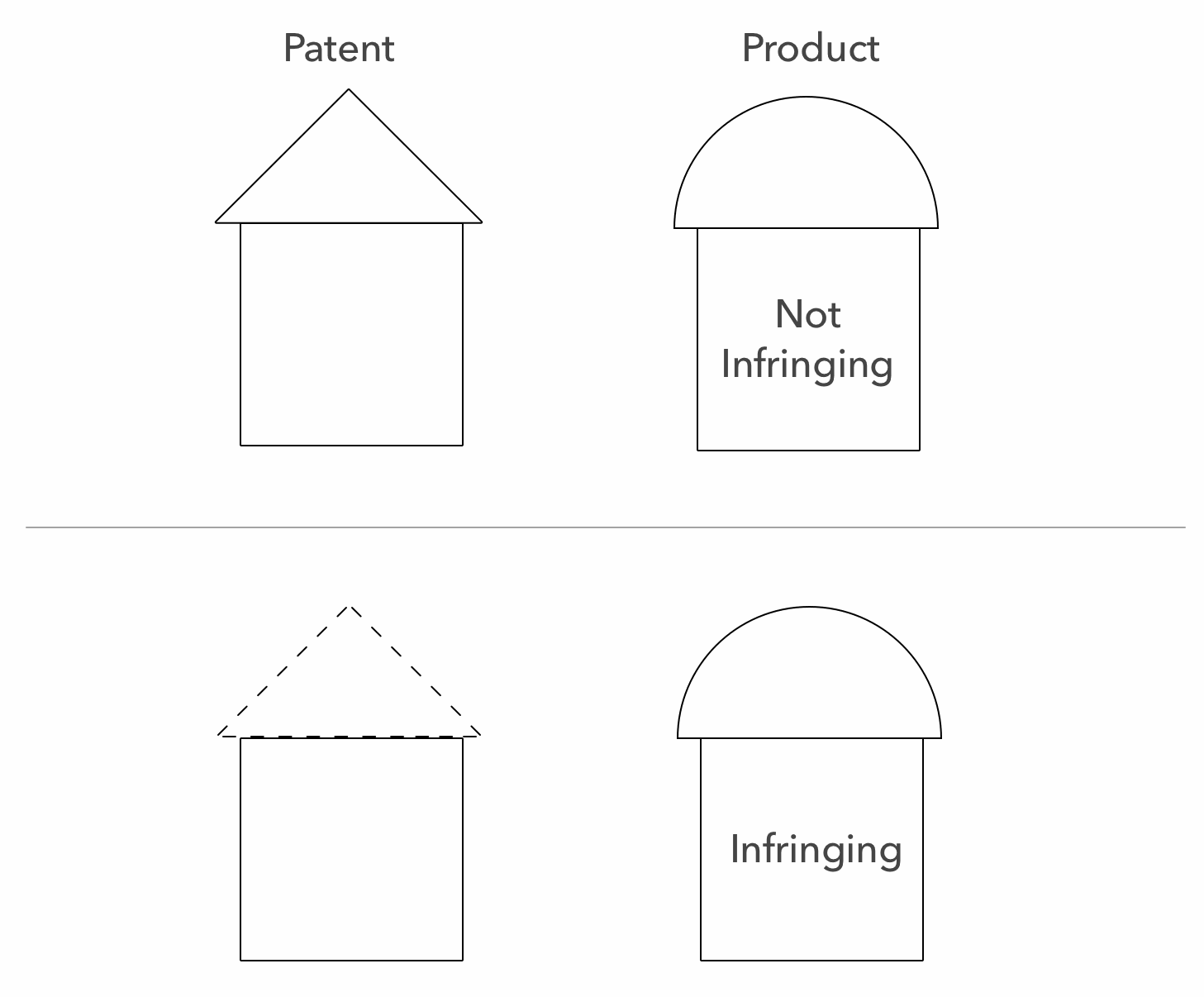

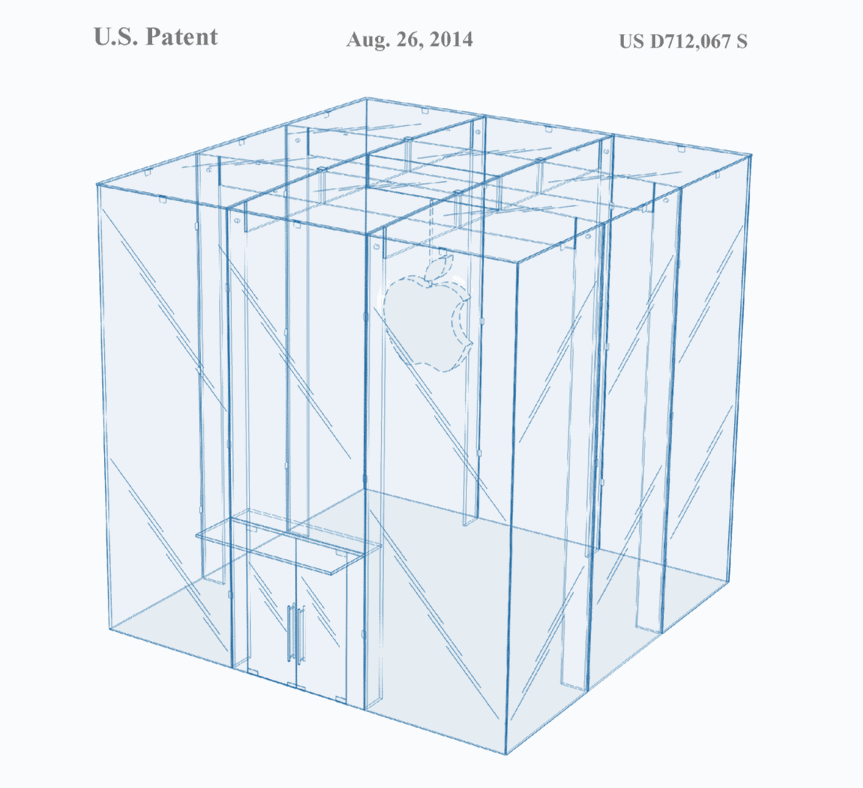

The drawings are the heart of a design patent. They define the design that is being protected. In design patent drawings, the difference between solid lines and dashed lines is critical. Solid lines identify the parts of the design that are actually protected by the patent. Dashed lines are used to show context or environment.

To be infringing, a competitor’s product must match all of the design patent elements shown in solid lines. This means that drawings with more solid lines are more difficult to infringe (i.e., easier for competitors to copy). More solid lines means narrower design patent protection. Again, this is because a competitor’s product is only infringing if it incorporates every element shown in solid lines. This is counterintuitive, but a simplified example may help:

Compare the “patent” drawing in the upper left to the “product” in the upper-right. The patent (upper-left) shows a square and a triangle in solid lines. Since the competitor’s product (upper-right) doesn’t have a triangle, it doesn’t copy every element shown in solid lines, and it’s not infringing the patent.

Now look at the patent in the lower-left. It has a square drawn in solid lines, and a triangle in dashed lines. This time, we ignore the triangle when we make the infringement comparison. Since the competitor’s product has the matching square element, it is infringing the design patent. More dashed lines create stronger design patents.

Examples of Design Patents

With this design patent law in mind, lets take a look at some famous designs and how they were protected. Note that the convention of using dashed lines didn’t start until the 1980 case of In re Zahn, 617 F.2d 261 (CCPA 1980).

Industrial Design Patent Examples

Furniture Design Patents

Furniture is prototypical design patent subject matter. Almost any new furniture design should be patented. For more examples, you can scroll through some of the patent Office’s illustrated “furnishings” category.

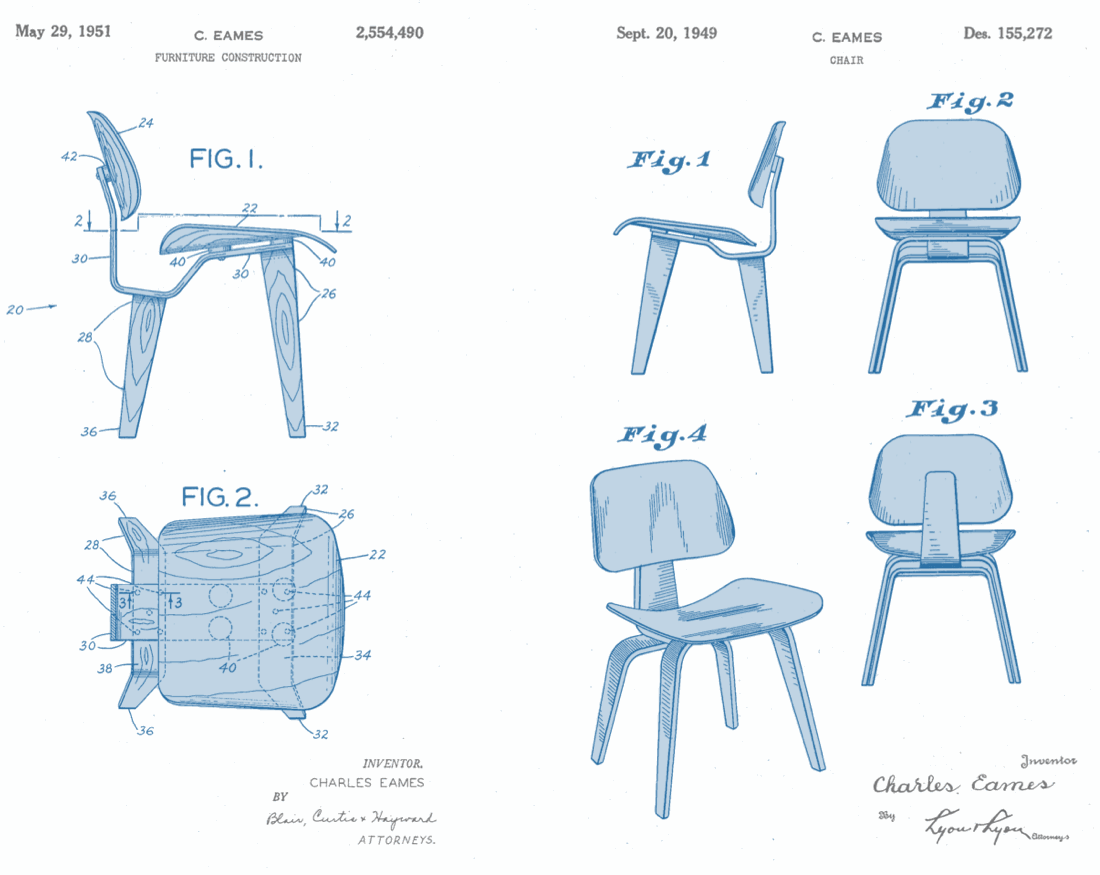

Charles Eames’ iconic chair for Herman Miller (1949):

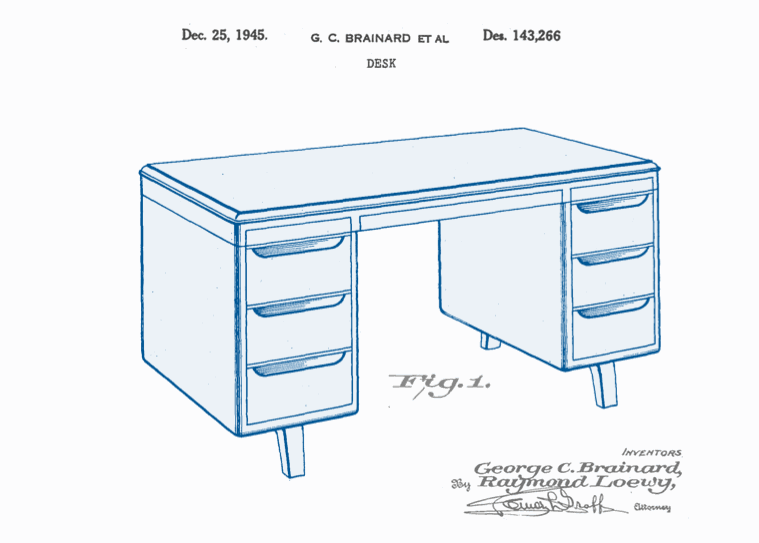

Raymond Loewy’s “mode maker” desk for General Fireproofing (1945). Also, check out some advertisements from the period.

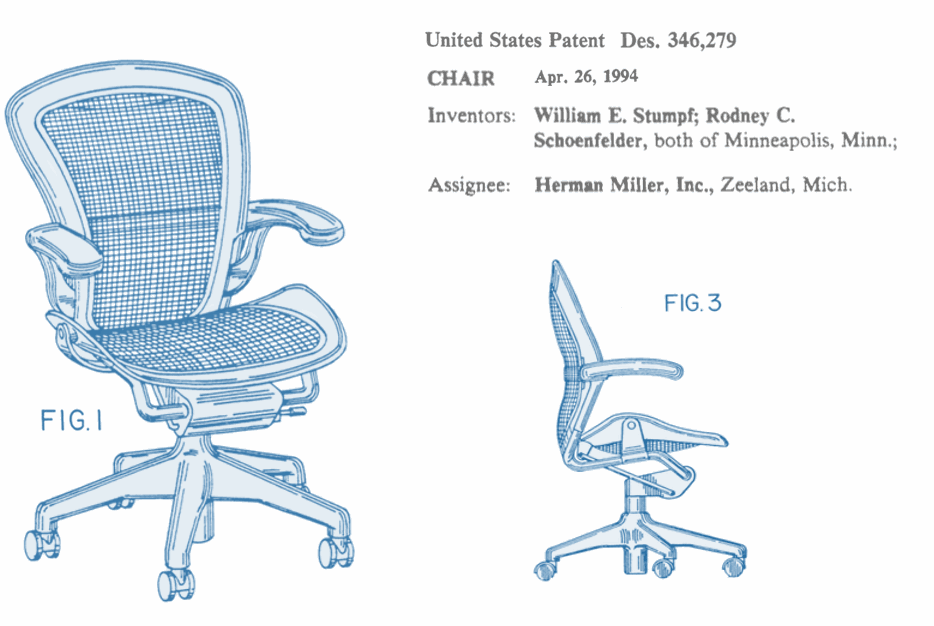

A design patent for Herman Miller’s famous Aeron chair. If you need to sit in an office all day, you need an Aeron chair.

Technology Hardware Design Patents

Building a hardware business isn’t easy, but a suite of design patents can often help protect early investments in building great products. Here are some hardware design patent examples.

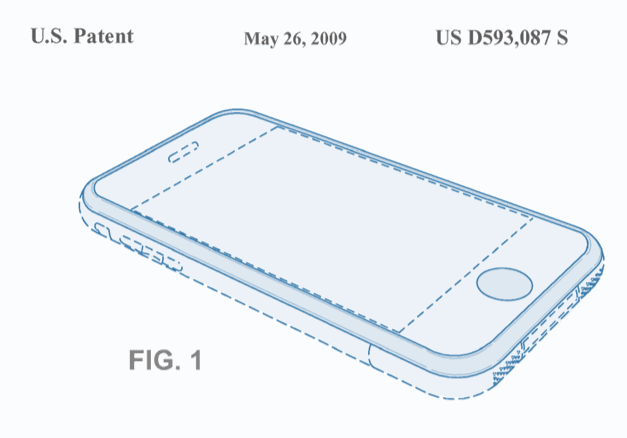

A design patent for an early iPhone hardware design (2009). Note how most of the iPhone is drawn in dashed lines, with only the button and bezel drawn in solid lines:

An iPhone design patent for both hardware and software combined (2013):

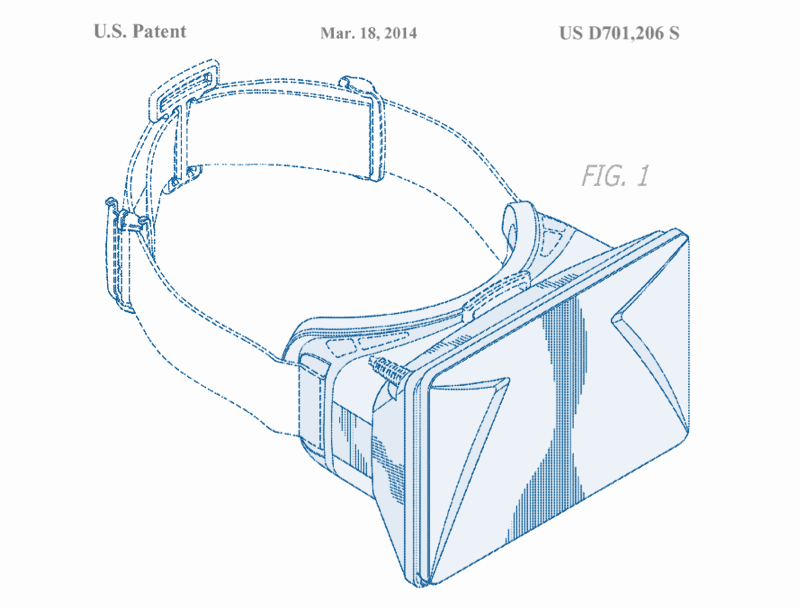

An Oculus Rift hardware design patent (2014). The strap is drawn in dashed lines:

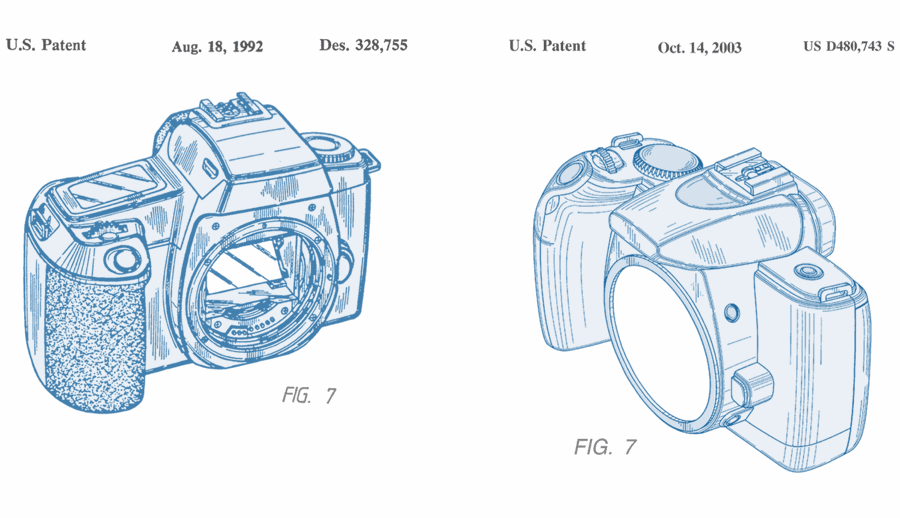

Two Canon DSLR design patents. The first from 1992, and the second from 2003. No dashed lines used in either:

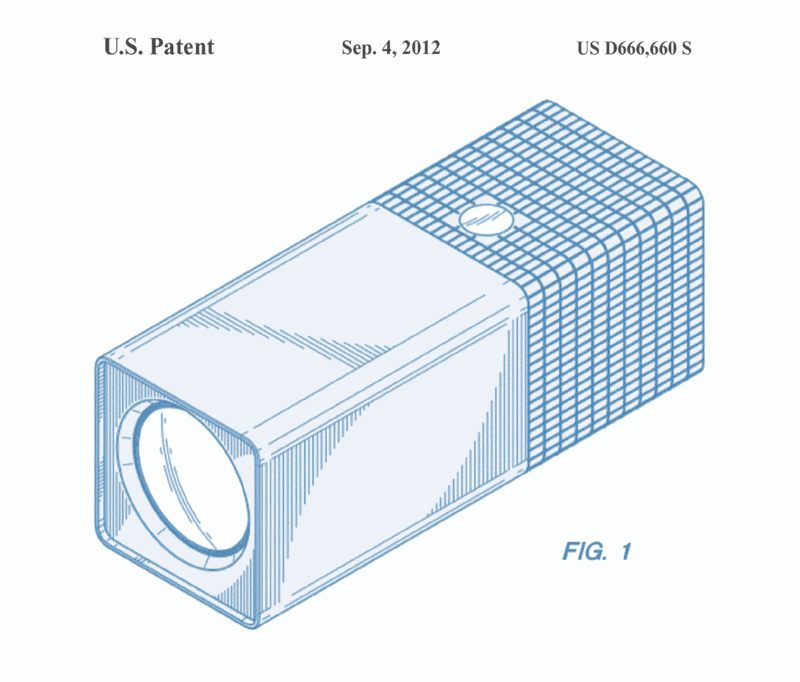

Lytro camera (first generation) design patent, 2012:

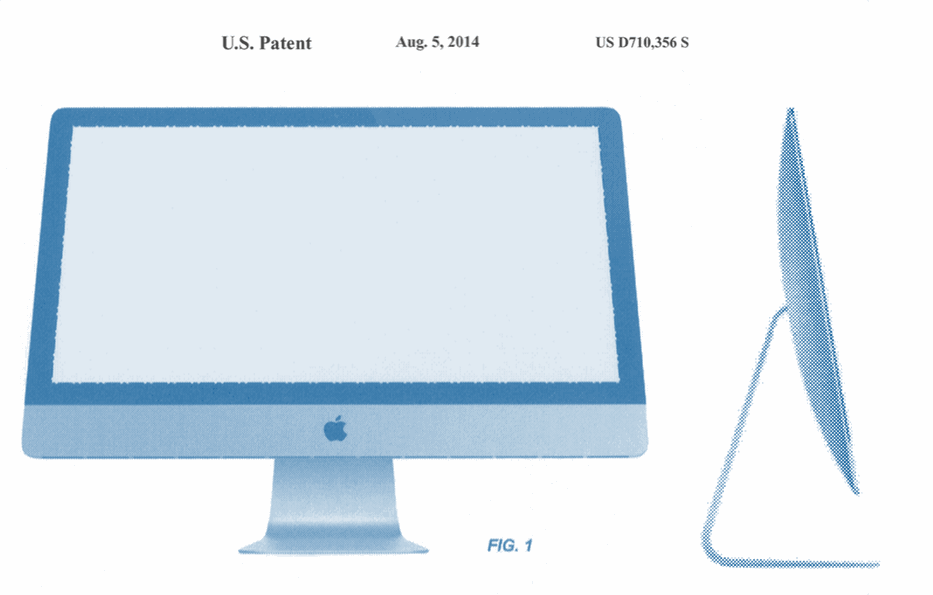

A design patent for the recent iMac (2014). Note that the drawings are essentially photographs, not line drawings. This is allowed.

Vehicles

A Harley Davidson design patent from 1919.

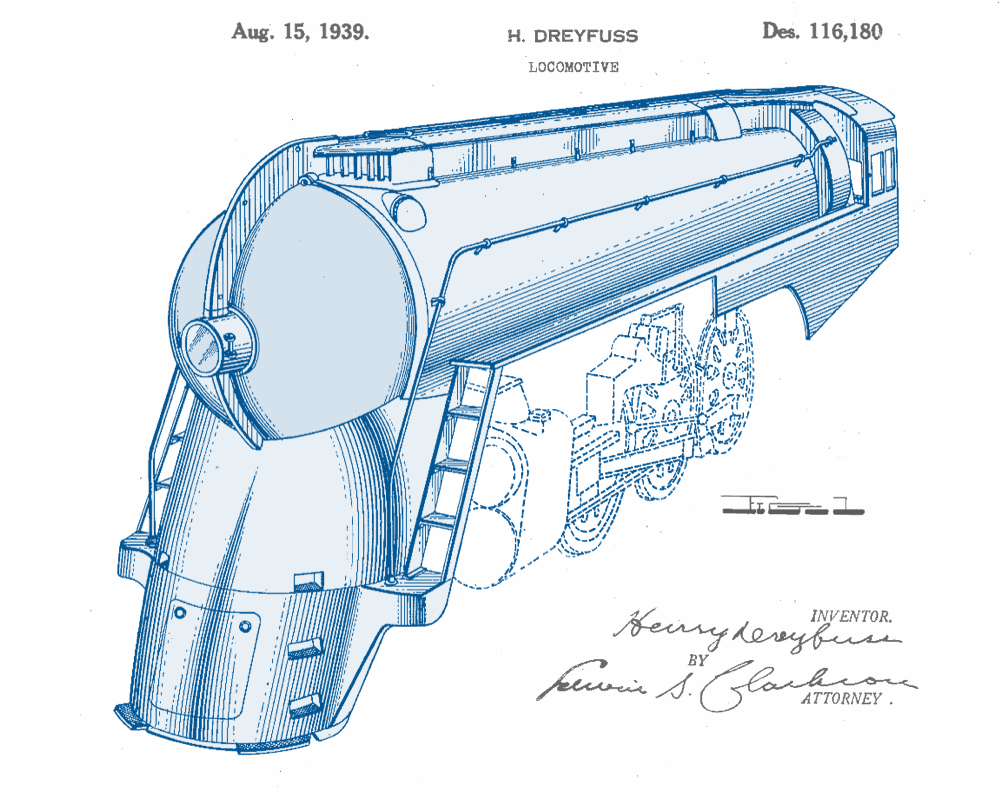

A design patent for Henry Dreyfuss’ famous Mercury Locomotive:

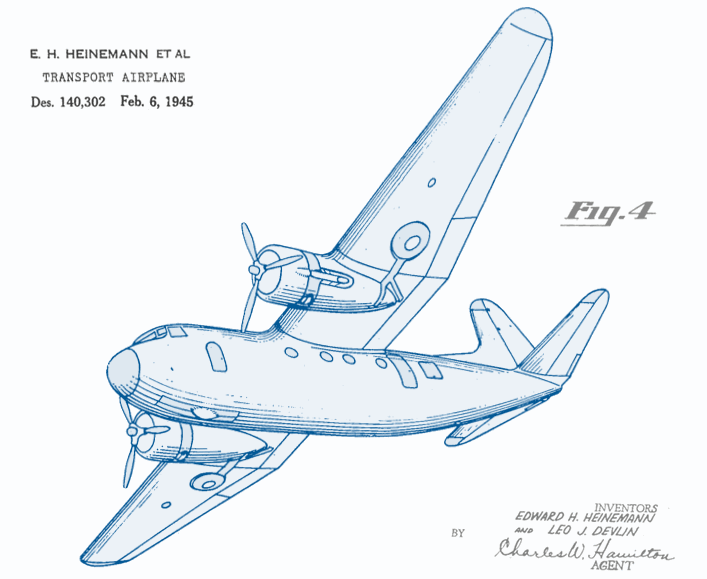

A design patent for the DC3 cargo plane (I think) from the Douglas Aircraft Company (1945):

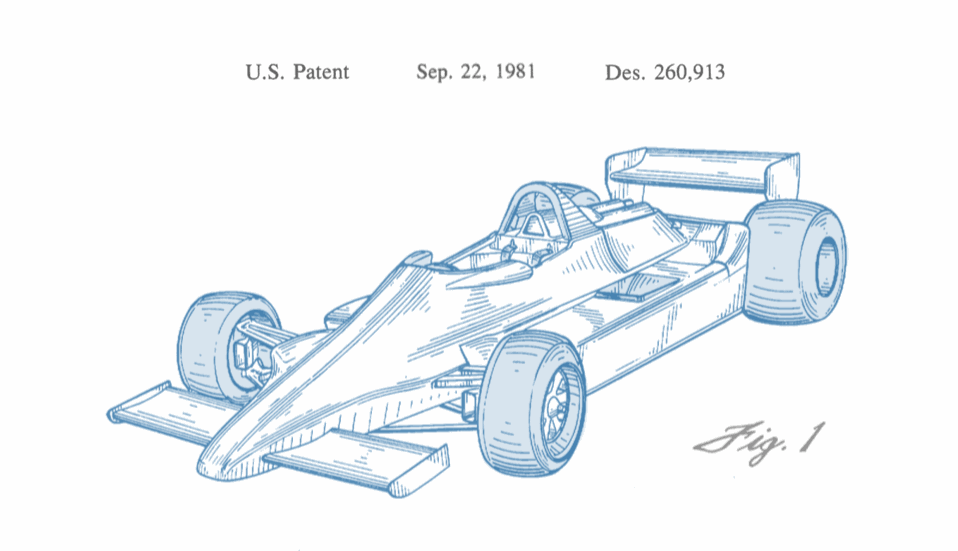

Colin Chapman design for an early 1980s (or late 1970s?) Lotus Formula 1 car.

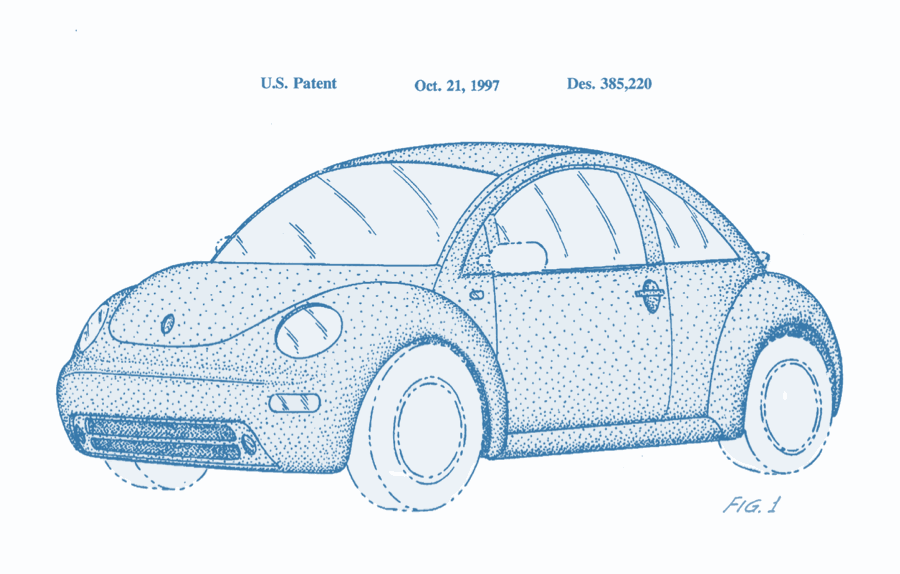

Volkswagen New Beetle, 1997.

Toys and Tools

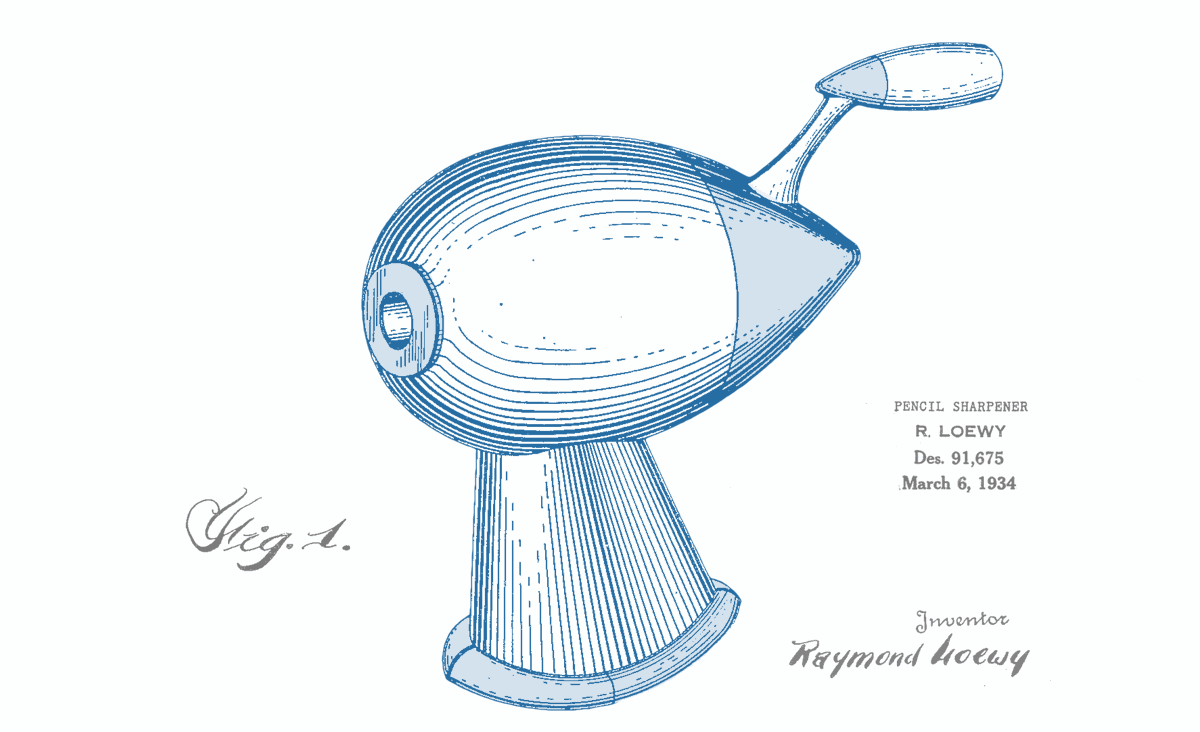

Raymond Loewy’s pencil sharpener, a design that became the symbol of the streamline movement.

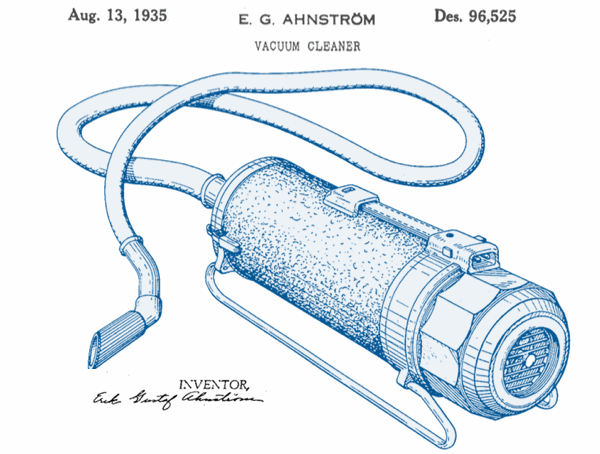

An Electrolux vacuum cleaner design patent (1939):

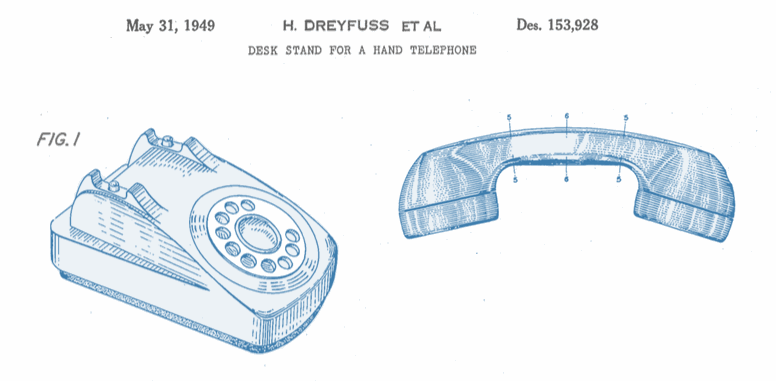

Two design patents for Henry Dreyfuss’ rotary phone (1949). The image on the left is for the stand, and the right is for the handset (separate design patents).

Godtfred Christiansen’s lego man (1979):

Architecture

Musical Instruments

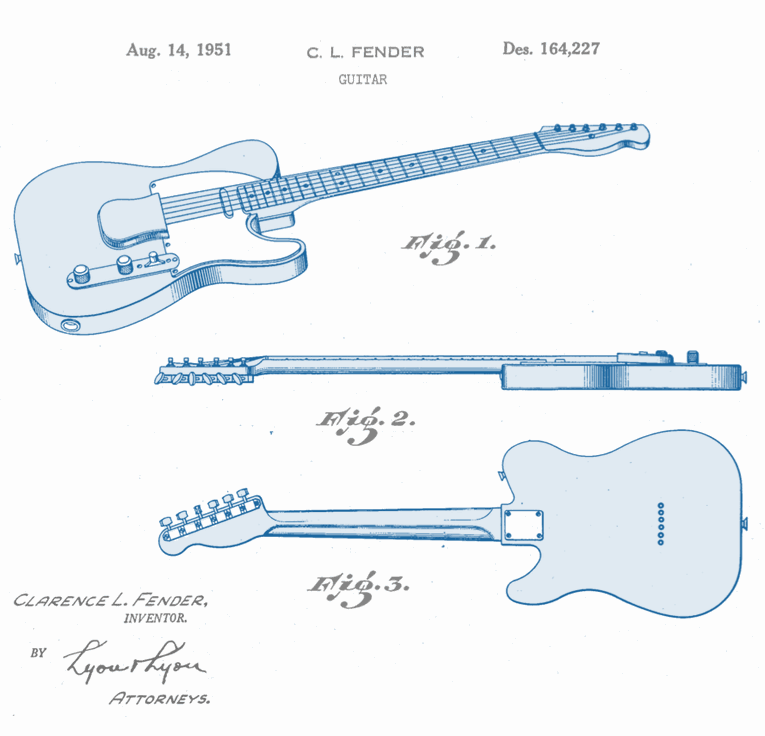

Clarence Fender’s electric guitar (1951). Fender’s Telecaster, the first commercial solid-body electric guitar, was the guitar played by legends like Elvis, Waylon Jennings, Eric Clapton (Yardbirds era), Muddy Waters, and more. (If you’re a bluegrass nerd, Clarence White also played one).

Digital UI Design Patent Examples

In the digital world, design patents can protect user interface icons, layouts, fonts, UI controls, transitions and a variety of animations, swipes and gestures. User Interface design patents are particularly important legal protections. “As far as the customer is concerned, the interface is the product”, and owning a unique user interface can provide significant market power. The UI Design patent examples below simply demonstrate how companies are using design patents to protect their UI elements. They are not necessarily examples of great design.

UI Layouts

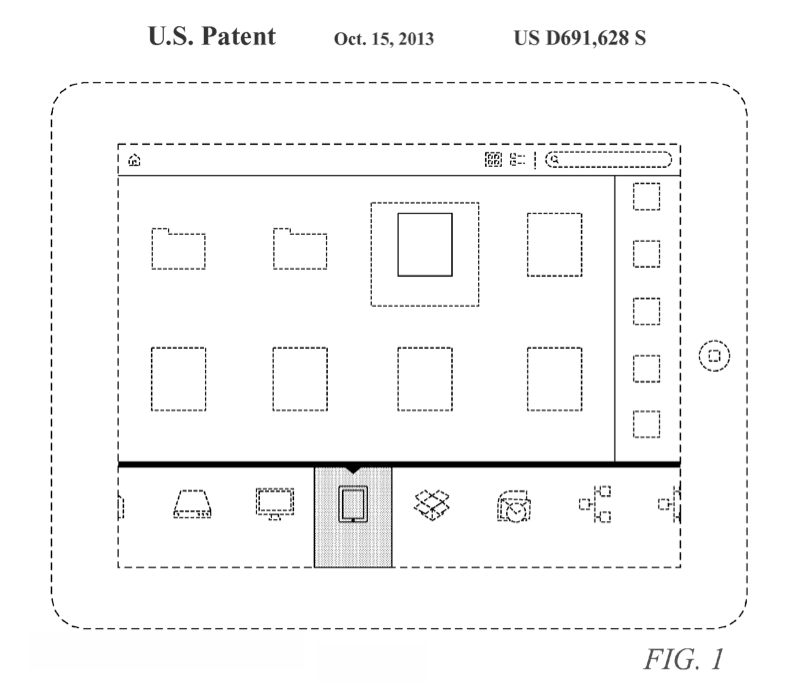

Design patents for UI layouts are among the more interesting and important type of UI design patents. A clunky UI makes a frustrating chore out of simple tasks like selecting files, navigating menus and launching applications. Carefully designed layouts, especially for phones and tablets, can make these tasks easier.

Adobe patented the layout of its iOS file selection system in D’628 (2013). Note the use of dashed lines to depict the tablet:

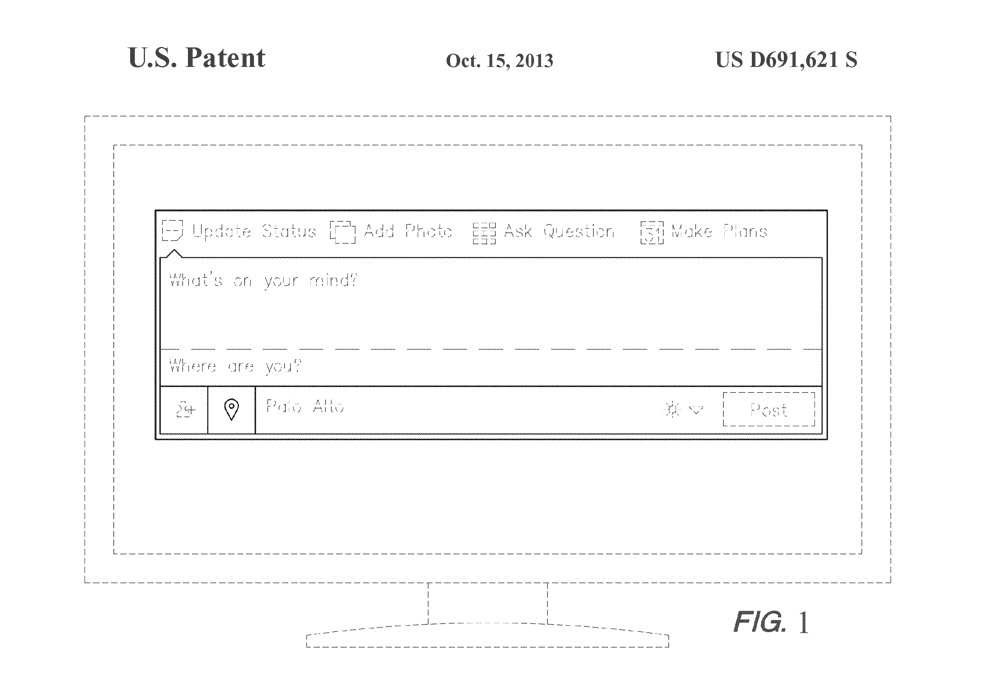

Facebook is more aggressive with its dashed lines. D’621, Facebook’s recent “status update” UI design patent (2013) uses dashed lines for the computer monitor and all of the text. The solid lines –showing the patented portion of the Facebooks UI– are limited to a few rectangles.

Apple is famously aggressive in its pursuit of UI design patents. Apple’s ‘666 design patent (left) protects UI with a bottom row of icons. Other than the 4 icons, everything else is drawn in dashed lines. Apple’s D’864 patent (right) is similarly sparse. It protects a UI with a few rows of icons, in the proportions of iOS on an iPad.

![]()

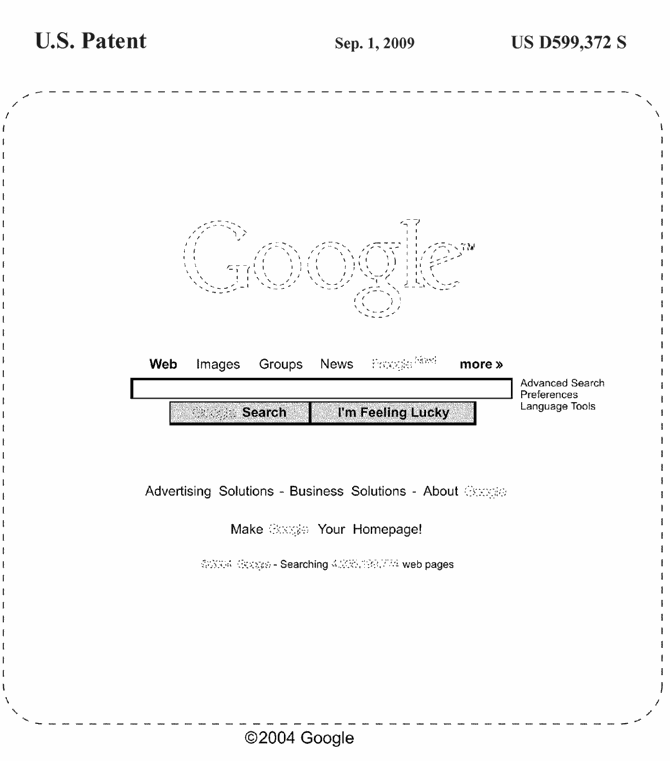

Google has a design patent on its famously simple landing page and search box (2009) (discussed at Patently-O blog). While the “Google” logo is shown in broken lines, much of the other text is shown in solid lines:

Animated UI Elements

Design patents can protect animations and transitions as well as layouts. The way a layout adapts to a new context or to user input is often a key UI innovation.

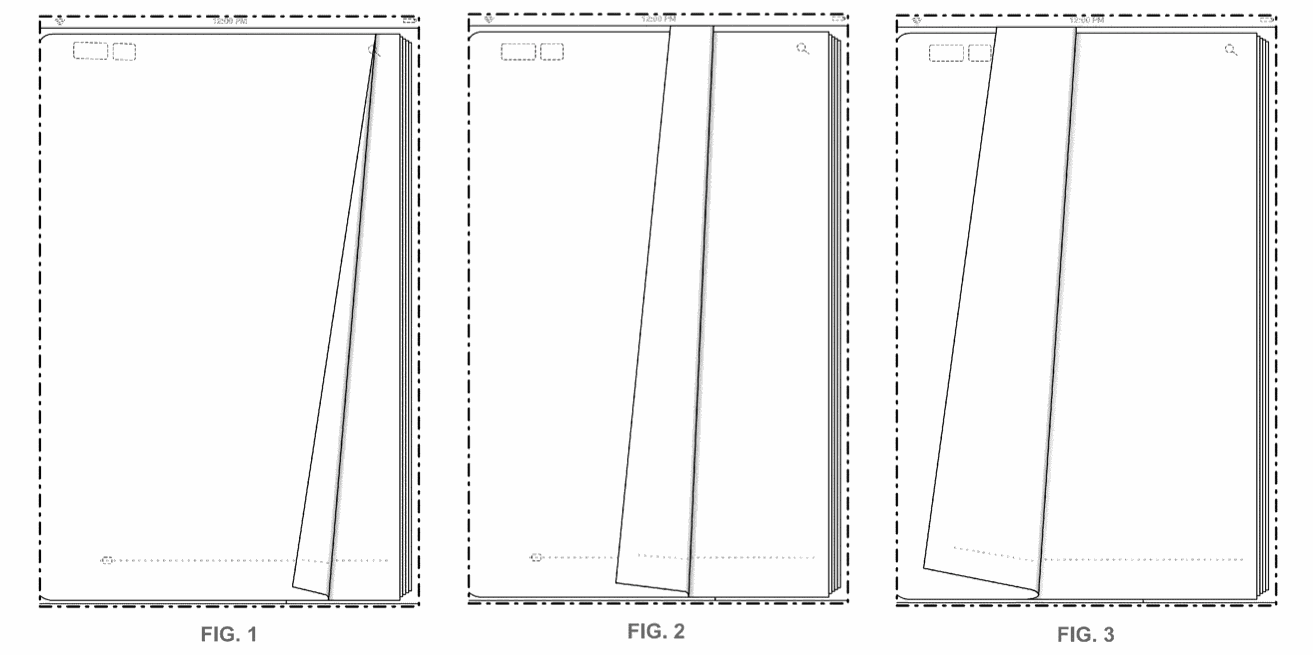

Apple’s iBooks page turn is an animated design patent shown in 3 positions.

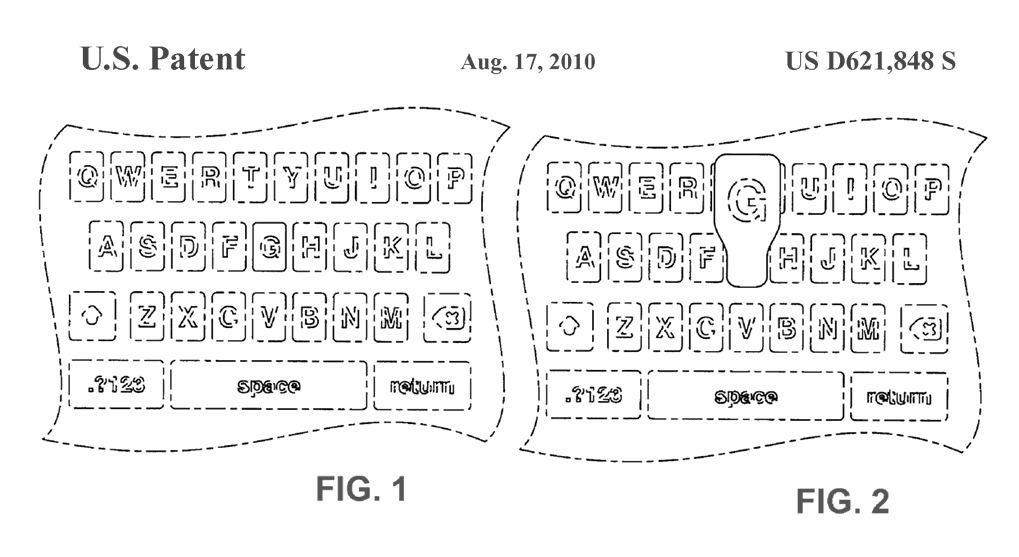

iOS Keyboard Animation shows how a key gives user-feedback by way of an expanding bubble above the selected key.

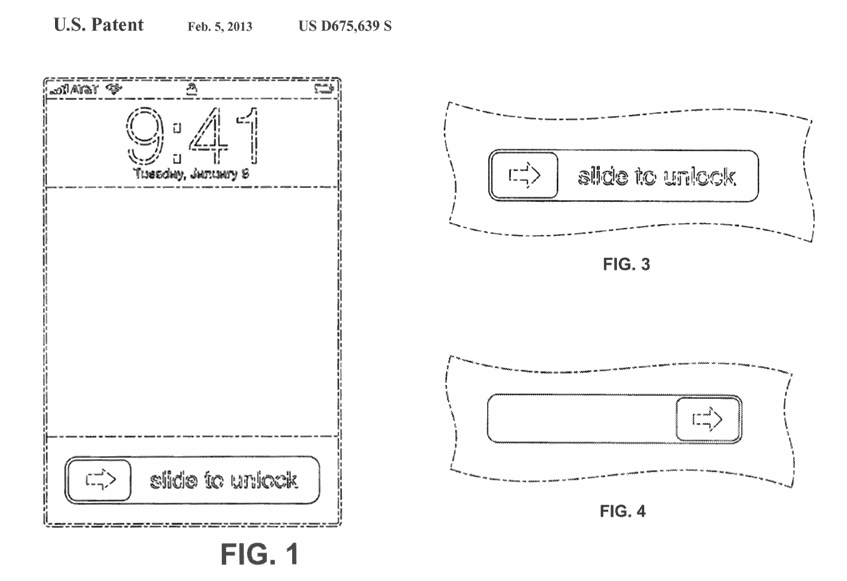

Apple’s iOS swipe-to-unlock is a good example of how to use a design patent to claim an animated UI element. Swipe-to-unlock also shows the UI feature in two different modes: ready (fig. 3) and activated (fig.4). Many other animated UI design patents can be claimed with a similar series of drawings.

Most of the design patent is dashed lines. This carefully defines the patent rights, and limits them to the solid-line “swipe bar.” Because of the dashed lines, this patent protects Apple against use of any similar swipe bar, regardless of what the rest of the OS looks like.

Icons

Facebook has a design patent on its two-silhouette “friend” icon. Notice that every detail except the icon is shown in dashed lines. This design patent only covers the icon.

![]()

Fonts and Typography

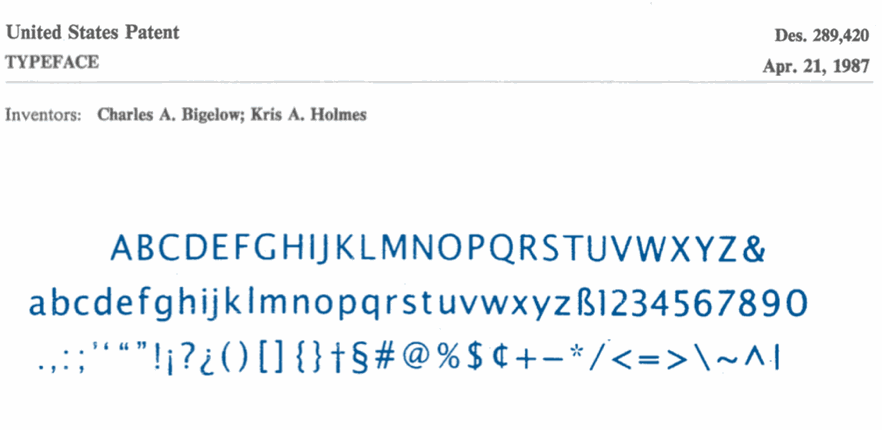

Fonts can be patented. Adobe regularly secures design patents for its fonts. This is particularly important because copyright law does not protect fonts themselves (although copyright will protect the software that draws fonts). Here’s an example of a typeface design patent. It’s from Charles Bigelow and Kris Holmes, for a Lucida Sans(?).

In addition to UI layouts, dashboards, animations, transitions, icons and typography, design patents can be used to protect nearly any other type of UI or UX element. UI design patents are an underused tool, especially in a space where competitors are happy to free-ride on your careful UI and UX research and design risk.

Design Patents Compared to Other Intellectual Property

Design patents are a strange amalgam of utility patents, copyrights, and trademarks. This section discusses the differences, and how these different IP rights can sometimes conflict, and other times overlap and bolster each other.

Utility Patent vs. Design Patent

A utility patent protects functional aspects of an invention, while a design patent protects new nonfunctional designs. Design patent applications are cheaper and faster than utility patent applications. A design patent application costs about $2-4,000 (total) and takes about a year to issue. A utility patent application costs between $8,000-20,000 (total) and lingers in the Patent Office for around 3 years before being issued as a patent.

To distinguish between a utility patent and a design patent, look at the patent number. If it starts with the letter “D” or “USD”, it’s a design patent. The design patent document is generally much shorter than a utility patent document. Design patents have a page or two of text followed by several drawings. Utility patents are bloated with long-winded written descriptions of technology that may drag on for tens or hundreds of pages.

Many designs can be protected by both design patents and utility patents. For example, this Eames Chair was patented as both a design patent and utility patent:

Likewise, interactive UI design elements can be protected by both utility patents and design patents. For example, Twitter’s pull-to-refresh is a utility patent. As is Apple’s pinch-to-zoom patent. Either could have also been protected as a design patent for a user interface.

Copyright vs. Design Patents

Copyright can protect many types of creative works, but this discussion focuses on software, UI elements, and works of industrial design.

Non-Functional. Both copyrights and design patents protect non-functional designs. Copyright law applies the non-functional requirement rigorously, while design patent law is lax about what it considers “non-functional.” Copyright protection rarely applies to a design that is even partly functional. Design patents, on the other hand, will protect functional aspects of designs, so long as the design isn’t entirely dictated by its function. It’s rare that a design would be wholly dictated by its function, as there is often ample room for aesthetic considerations.

Duration. Copyright protection lasts longer. Design patents protect industrial design for 15 years. Copyrights protect works of creative authorship for 95 years (often longer, but sometimes shorter, according to some complicated rules).

Infringement. A copyright can only be infringed if there is “copying.” That is, the infringer must have seen the original copyrighted work at some point. Coincidental similarity is not enough for copyright infringement. Design patents can be infringed by sheer coincidence. For example, someone who has never seen an iPhone or Apple’s design patents can still infringe them. Unlike copyright, there is no “fair use” defense for design patent infringement.

Trademark vs. Design Patent

Trade dress, a branch of trademark law, can also protect the non-functional appearance of a product, software design or of certain types of UI elements. But unlike design patents, trade dress law revolves around brand identification and protecting business reputations.

Distinctiveness. Trade dress rights are more difficult to establish than design patent rights because trade dress requires “distinctiveness.” That is, the owner must prove that the public recognizes the design as a distinctive indicator of the product’s origin (from a particular company). Product packaging trade dress may be “inherently distinctive” and registered as a trademark at the USPTO based solely on its appearance. TMEP 1202.02(b)(ii) Distinctiveness and Product Packaging Trade Dress. Product design trade dress, however, is never “inherently distinctive” and always requires an expensive and time-consuming process of collecting evidence and making legal arguments to the USPTO trademark examining attorney. TMEP 1202.02(b)(i) Distinctiveness and Product Design Trade Dress.

Infringement. The owner of trade dress rights can prevent a second company from using design elements that are so similar to the protected design that consumers will be confused. Specifically, they will be confused into thinking the second company’s product is made by the first company, or that the second company is somehow associated with the first company. Put differently, trade dress is infringed if a defendant’s design will confuse consumers into thinking the defendant’s product is actually made by–or somehow associated with–the plaintiff.

Functionality. Trade dress only protects non-functional aspects of a design. Like copyright law (and unlike design patent law), this prohibition against functional design elements is strictly enforced. TMEP 1202.02(a) Functionality of Trade Dress. In litigation, a trade dress plaintiff is required to prove that the trade dress is non-functional. In design patent litigation, a judge will presume the plaintiff’s design patent is nonfunctional, and the defendant can only disprove it with clear and convincing evidence.

Perpetual. Trade dress rights, once established, can be perpetual. Unlike design patents, trade dress rights do not have a set expiration date. Trade dress only expires when a company stops using the trade dress designs on its products.

Design Patent Strategies

Since design patents provide a potent legal right, and are relatively affordable, they should play a role in the IP portfolio of nearly any company with consumer-facing products. For certain products, design patents can be combined with utility patents, with copyright registrations, and/or with trade dress registrations to round out an intellectual property portfolio.

Design Patent Strategies for Industrial Design

When developing a product, think about which design features are new and innovative, and which design features will connect with consumers. Identify the portions of the design that are most likely to attract consumers. Any design elements that is both new and attractive to consumers may merit a design patent, or perhaps a series of design patents. A series of separate design patents is often much stronger than an a lone patent. In these separate design patents, most of the overall design should be depicted in dashed lines, while only the individual highlighted component is shown in solid lines.

Timing. Ideally, design patent applications should be filed before the produce first hits the market or is otherwise published or advertised. However, for many purposes, it may still be possible to file a design patent within the first year after the design becomes public.

Combine with Trade Dress. Design patents can also be used to jump-start trade dress protection. Carefully timed design patent protection can start before a product hits the market, but will only last for 15 years. Trade dress protection, on the other hand, generally does not start for at least 5 years after the product has been on the market. However, once trade dress protection starts, it does not expire until the product design is abandoned.

Combine with Copyright. Design patents can also be combined with copyright protection. Designers should consider registration of the copyright in their designs, as a 3 dimensional sculpture, to further bolster the intellectual property portfolio.

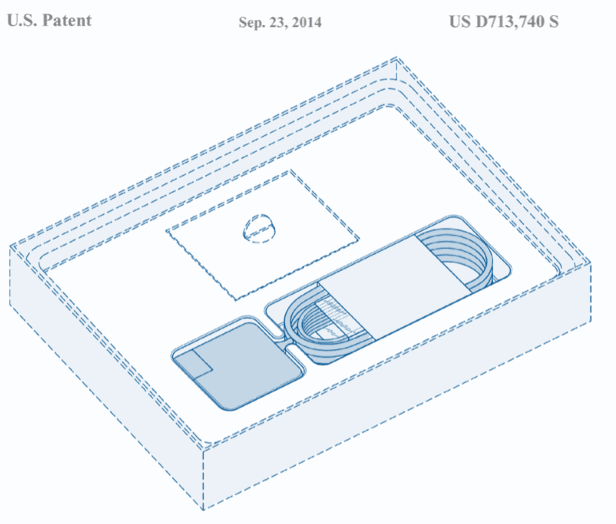

Packaging. Design patents can touch nearly any part of the user experience. Companies that invest in their packaging design and unboxing experience should strongly consider design patent applications for their packaging.

Product packaging is also a strong candidate for combined design patent and trade dress protection. This is because product packaging, unlike product design trade dress, may be “inherently distinctive” and therefore registered as a trademark far more easily. TMEP 1202.02(b)(ii) Distinctiveness and Product Packaging Trade Dress.

Digital User Interface Design Patent Strategies

Major tech companies like Apple, Samsung and Microsoft pursue UI design patents in a big way. Microsoft is aggressively growing its portfolio of 1,800 UI design patents. Apple and Samsung have patented hundreds more.

Other companies take a more focused approach. Facebook, Google, Adobe, and Autodesk each have a handful of design patents. This focused design patent strategy is often the most cost-effective. Smaller companies can follow it by carefully selecting its best UI design features for patenting, and spend its resources on acquiring the highest value design patents.

As a company moves from generic frameworks to custom UI elements, it should start considering UI design patents. A lean startup launching a MVP from pre-packaged frameworks like Bootstrap might not have much new design to protect. But when it starts to customize its user interface –especially with innovative design elements or layouts– it should start thinking about design patents.

For critical user interface elements, think about your information architecture, navigation structure, buttons, icon and transitions. Which elements came from a pre-packaged framework? Which ones were designed from the ground up? Several drawings should be produced, and the drawings should carefully distinguish the custom UI design elements from the pre-packaged elements. Depict custom elements in solid lines, and the standard elements in broken lines.

Drill down into the design. How granular can you make the custom elements before they just become standard design objects? If you can identify several granular UI levels that are not just off-the-shelf elements, you can file several design patents. In each of these design patents, only one of the granular design components should be depicted in solid lines.

If you have existing utility patent applications, you can use them as a springboard for design patents (within 6 months). You can pull design patents out of the existing utility patent drawings, and even benefit from the earlier filing date of your utility patent application.

A company’s unique UI design may be one of its most valuable assets. Without design patents, the UI design may be left unprotected. Copyrights alone are not enough. While copyright can protect creative designs, copying is subject to a number of restrictions, including fair use. Trademarks alone are not enough because “trade dress” rights are difficult to establish, particularly for product configurations. Trade dress rights require several years of use and heavy marketing to properly associate a startup’s UI design with its brand, and thus achieve some level of trade dress protection (some exceptions apply).

Conclusion

Creating engaging design can be a slow, iterative, and research intensive process. If you’re investing resources, and you want some degree of reasonable protection, consider a handful of design patents.